When Secondaries Should Come First

Investors seeking to gain initial exposure to private investments should actively consider secondaries, rather than funds-of-funds, as the very first step to constructing a long-term private equity portfolio

- A secondary transaction can begin generating distributions as early as day one of the investment, accelerating the cash distributions within a private investment program, and mitigating the J-curve effects of private investing.

- Secondary deal dynamics, particularly pricing, often define the success of a transaction more so than a particular market, strategy, manager, or portfolio. Partnering with a disciplined secondary manager is critical to understand where the best opportunities are and execute them.

- Because secondary funds are constrained by the supply of opportunities during the investment period and the price to acquire interests, investors should choose secondary managers for their ability to effectively underwrite assets, rather than to try to gain exposure to specific funds or asset classes.

David Shukis and David Thurston, “The 15% Frontier,” Cambridge Associates Research Report, 2016.

In the search for returns, more investors are turning to private investments for the first time or seeking ways to increase their allocation to these strategies. Recent Cambridge Associates research indicated that, on average, portfolios with higher allocations to private investments—at least 15%—have outperformed portfolios with lower allocations. If seeking to increase exposure to private investments, investors of all types and sizes must develop an appropriate plan to reach the 15% “frontier.” But how to get there?

Investing directly in high-quality private funds is the ideal approach. However, the task of building a robust and high-quality direct portfolio can be daunting. Beginners are often overwhelmed with the tasks of understanding, mapping, and evaluating the range of options for strategies, geographies, and investable funds. In addition, some investors cannot invest in funds with high minimum commitment sizes, or are unable to employ the necessary internal staff to build and implement a successful direct private investment portfolio. In a “walk before you run” approach, rather than starting with direct fund investments, many investors build exposure and knowledge through the use of funds-of-funds (FOFs), and some start programs with secondary funds.

For a fee, FOFs and secondary funds both offer investors diversified portfolios (see sidebar on the next page for brief background on these strategies). However, their contributions diverge from there, making it important to evaluate these strategies side-by-side to compare cash flow characteristics, return profiles, and exposures, among other features. The purported benefits of FOF investing include gaining knowledge about the market, building diversified private investment exposure, developing relationships with managers for future direct primary commitments, and earning a compelling investment-level return. The purported benefits of secondary funds are all of the above, but with typically earlier distributions mitigating the J-curve effect so common for nascent private investment programs.

Secondaries, similar to FOFs, may be used to initiate and ramp up a private investment program, or also as a stable, ongoing base. Building initial exposure to private investments via secondary funds achieves many of the desired outcomes for beginners with limited resources and in-house knowledge. FOFs are most effective at providing primary exposure to highly targeted strategies or geographies.

In this paper, we review the primary considerations for implementing private investments through secondary funds rather than FOFs or direct funds.

Funds-of-Funds in Brief

For a fee—typically less than 1% management fee and 5% carried interest (on top of the fee/carry of the underlying primary funds)—FOF managers commit capital to a diversified portfolio of primary funds. An FOF will usually commit to funds over two to three vintage years before the manager raises a successor vehicle. FOFs may be generalist, investing across strategies and/or geographies, or targeted, investing in a specialized area. FOF managers should demonstrate an ability to consistently identify and gain meaningful allocations to high-quality funds, and construct portfolios with appropriate diversification.

The private equity FOF industry became mainstream in the 1990s, but gained popularity in the subsequent decade as more investors sought exposure to private investments. FOFs offered an accessible solution and the strategy reached a fundraising peak of $40.3 billion in 2007, according to Preqin. Investor support for FOFs waned in the aftermath of the global financial crisis given the impact of FOFs’ extra layer of fees and long investment horizons on performance. Still, a base level of investor interest in diversified FOF vehicles has persisted and FOFs form the core of many ongoing private investment programs. At the same time, most FOF managers have adapted their businesses to better cater to the needs of larger investors, emphasizing services such as customized separate accounts, niche strategies, and co-investment offerings.

Secondaries in Brief

Private equity fund commitments are inherently illiquid; secondary funds build portfolios by purchasing existing positions in single funds or groups of funds from LPs seeking early liquidity from these positions, often at a discount to carrying value (net asset value or NAV). The result is a fund comprising a diversified portfolio of seasoned private investment positions. Beyond the straightforward approach of acquiring “slightly used” LP interests, many secondary managers also participate in more complex transactions; for example, direct private company secondaries, structured deals, or deals involving the use of leverage. Secondary fund managers charge a management fee of roughly 1% and carried interest of about 12.5%, and typically invest a single fund over a two- to three-year period.

The secondary market has been active for two decades, but 2010 marked its rise in popularity as both an asset class and portfolio management tool. According to data from Preqin, annual fund-raising volume for secondary funds averaged just under $9 billion from 2000 to 2011; since 2012, annual fund-raising volume has averaged $23 billion, with over $27 billion raised in 2016.

Annual secondary transaction volume averaged $9.8 billion from 2002 to 2009, based on data from Greenhill, before increasing drastically between 2010 and 2016, averaging more than $30 billion and reaching a high of $42 billion of closed transactions in 2014. To put this in context, secondary transaction volume averaged between 1.6% and 8.4% of primary fund commitments over this period. As a derivative of the primary private markets and a widely accepted portfolio management tool, secondary volume may be volatile, but the market is certainly here to stay.

Many Happy (and Early) Returns

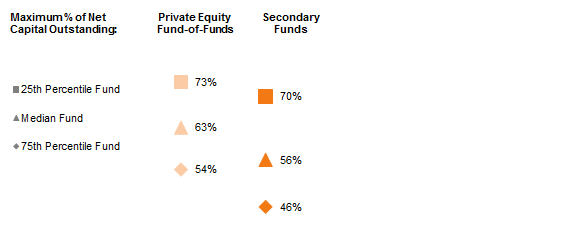

Secondary funds typically purchase “slightly used” limited partnership (LP) interests—typically between 50% and 80% funded—with a sizable upfront cost. Some drawdowns may occur for follow-on investments later in a secondary fund’s life, but these capital requirements are often offset by other distributions from the portfolio. Importantly, because a secondary fund’s underlying investments are already seasoned, a secondary transaction can begin generating distributions as early as day one of the investment, accelerating the cash distributions within a private investment program. Secondary funds typically take seven years to reach a distributed to paid-in capital (DPI) multiple of 1.0x, with 40% of that capital distributed in the first five years alone, which is unusual for any private equity strategy and desirable for that reason (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Comparing Distributions for Secondary Funds, Private Equity Funds, and Funds-of-Funds

As of June 30, 2016

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Notes: Chart compiled using cash flow data from all private equity-focused funds-of-funds (defined as those not predominantly focused on venture capital or hard assets) and secondary funds in Cambridge Associates’ database as of June 30, 2016. Funds formed after 2013 are too young to be analyzed and were excluded. Analysis includes 169 secondary funds of vintage years 1991–2013, 1,926 global private equity funds of vintage years 1986–2013, and 350 private equity-focused funds-of-funds (defined as those not predominantly focused on venture capital or hard assets) of vintage years 1995–2013.

Contrast this with FOFs, which typically take longer to both deploy and return capital than both primary and secondary funds. Depending on the strategy, FOFs commit to underlying managers over a two- to three-year period, and then the underlying managers invest capital within their investment period (which could take up to six years). Thus, investing in an FOF may mean meeting capital calls as late as year nine of the FOF’s life and waiting anywhere from 12 to 15 years to fully liquidate. Private equity FOFs typically take an average of 11 years or longer to reach a DPI of 1.0x, with just 13% of distributions occurring in the first five years.

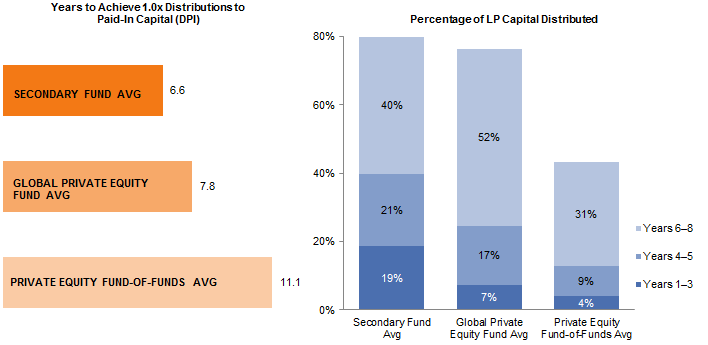

In terms of performance, secondary funds should and do offer a more narrow and more consistent band of returns compared to FOFs. One might expect FOFs to demonstrate greater upside potential than secondary funds since they are a blind pool with a long investment period and earlier investments in assets with prospects for high growth. Not so. In aggregate, as of June 30, 2016, secondary funds reported stronger results than FOFs on a pooled internal rate of return (IRR) and total value to paid-in capital (TVPI) basis. The median secondary fund outperformed the median FOF on these measures in the majority of vintage years, including the older vintages when FOFs should theoretically have the benefit of greater seasoning (Figure 2). In some periods, FOFs outperformed secondary funds by a small margin. This occurred in periods of market frothiness, suggesting that secondary fund investors have to be especially careful when selecting managers to invest in during these times.

Figure 2. Comparing Median Returns for Secondary Funds and Funds-of-Funds

Vintage Years 1998–2011 • As of June 30, 2016

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Notes: Returns represent medians for the Cambridge Associates Fund of Funds and Secondary Funds indexes, which include data compiled from 620 funds-of-funds (excluding real assets) and 202 secondary funds formed between 1986 and 2014. Private indexes are pooled horizon internal rate of return (IRR) calculations, net of fees, expenses, and carried interest.

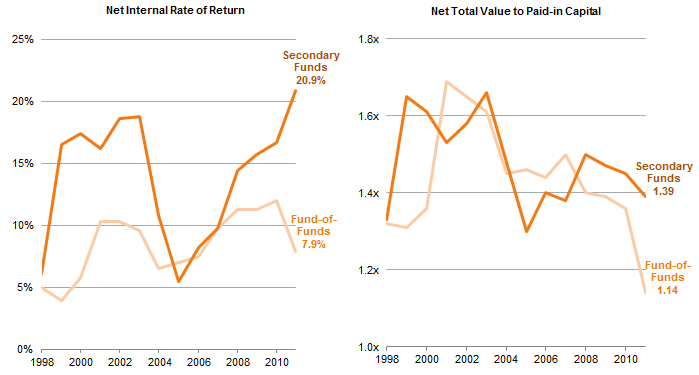

Perhaps Too Good of a First Impression, But Valuable for “IRR Maintenance”

Early IRRs for secondary funds can be meaningfully overstated due to the discount and mark-up effect of purchases often made at a discount and then written up in subsequent reporting periods, and typically tempers a few years into a fund’s life. Results of very recent funds or deals may look especially attractive, but do usually come down over time. This effect, in combination with early distributions, mitigates the J-curve typically experienced by direct fund investors and certainly by FOF investors (Figure 3). The IRR of a private equity fund usually follows a J-shaped curve—the IRR is low or negative in the early years as the manager draws capital for investments and fees. The IRR increases as the value increases over time and exits occur. Mathematically, the IRR calculation (the “depth” of the J-curve) is heavily influenced by early cash flows. New private investment programs are often in an overall J-curve, meaning the program is not self-funding, which requires other sources of capital and can strain an investor at inopportune times. The return profile of secondaries can attenuate the J-curve effect in a nascent portfolio, accelerating the receipt of the benefits of private investing.

Figure 3. Comparing Cash Flow Characteristics for Secondary Funds, Private Equity Funds, and Funds-of-Funds

As of June 30, 2016

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Notes: Chart compiled using cash flow data from all private equity-focused funds-of-funds (defined as those not predominantly focused on venture capital or hard assets) and secondary funds in Cambridge Associates’ database as of June 30, 2016. Funds formed after 2013 are too young to be analyzed and were excluded. Analysis includes 169 secondary funds of vintage years 1991–2013, 1,926 global private equity funds of vintage years 1986–2013, and 350 private equity-focused funds-of-funds (defined as those not predominantly focused on venture capital or hard assets) of vintage years 1995–2013.

The elevated nature of secondary fund IRRs—or secondary transactions, for that matter—can also contribute to the overall performance of a largely established private investment program. For investors that do not have overall J-curve concerns, the yield and return of secondaries still adds a level of diversifying private investment returns to mature programs. Once a program is fully established, some investors maintain exposure to secondaries through funds or buying interests directly for a few reasons: for “maintenance” of IRR at a minimum, to increase exposure with select managers, or as part of an overall strategy. That said, investors should continue to monitor the return potential of secondaries to determine if maintaining exposure is warranted.

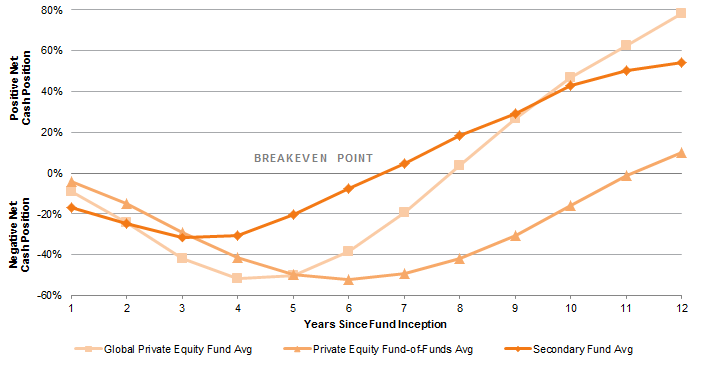

Less Money Down

At any given point within a secondary fund’s life, the maximum cost of net capital calls (out of pocket exposure) represents roughly 50% to 75% of investor capital. As shown in Figure 4, secondary funds typically utilize less investor capital compared to private equity FOFs. Out of pocket exposure is defined as net cumulative cash flows as a percentage of limited partners’ commitments. Contributing factors to this profile for secondary funds include distributions offsetting contributions early in a fund’s life and the utilization of structures including deferred payments and leverage. 1 Secondary funds may not actually call or invest 100% of commitments, and investors should consider this in their planning as they seek to deploy a target amount of capital into the strategy.

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Notes: Chart compiled using cash flow data from all private equity-focused funds-of-funds (defined as those not predominantly focused on venture capital or hard assets) and secondary funds in Cambridge Associates’ database as of June 30, 2016. Funds formed after 2013 are too young to be analyzed and were excluded. Analysis includes 197 secondary funds of vintage years 1991–2013 and 334 private equity-focused funds-of-funds of vintage years 1988–2013.

Market Factors—as Always—Influence Outcomes

While secondary funds have something to assess (especially compared to FOFs), they can only buy what is for sale at any given point in time, and must navigate the transaction environment at that moment in time. Secondary deal dynamics—particularly pricing—often define the success of a transaction more than a particular market, strategy, manager, or portfolio.

Secondary interest pricing levels, which change as a function of demand for that exposure and the supply of opportunities, materially impact returns. Data from Greenhill show that due to high demand and market exuberance, secondary managers regularly paid premiums in the years just prior to the global financial crisis—and in these years, secondary funds have posted their worst results. Partnering with a disciplined secondary manager is critical, especially in an increasingly competitive market, to understanding where the best opportunities are and executing them. For example, the best deal could be a great asset managed by a lower-quality general partner, provided the secondary fund could purchase the asset for discounted pricing with good exit visibility.

More “Mr. Right Nows” than “Mr. Rights”

Secondary fund managers are focused on earning their target return for LPs, building portfolios of LP interests with significant backward-looking vintage year exposure across what is likely a much wider range of managers by quality than would be selected by an FOF. The supply of opportunities during the investment period and the prices at which secondary funds are able to acquire interests are driving factors. In addition, secondary funds typically deliver over-diversification with their resulting portfolios, with dozens upon dozens, and sometimes hundreds, of underlying positions. Secondary fund investors can leverage and learn from the resulting portfolio exposures for future primary fund commitments, although the quality pickings may be slimmer than anticipated and future access not preordained.

These investment conditions also make it difficult for an investor to use secondary funds to gain exposure to a specific strategy, region, or manager. That said, most generalist secondary funds tend to weight buyouts most heavily, likely because this is the primary market with the greatest volume. Buyout assets also carry less risk and fewer binary outcomes than venture or other strategies. Despite recent growth in specialized secondary strategies such as real estate, venture capital, and emerging markets, the stability and cash flow predictability of more stable, mature assets like buyouts means most secondary funds will have significant developed markets buyout exposure. Ultimately, investors should choose secondary managers for their ability to effectively underwrite assets, rather than their exposure to specific funds or asset classes.

Keeping the “Fun” in Fund-of-Funds

While generalist FOF options exist, these have become less popular in recent years, primarily due to less attractive historical results. Indeed, in order to keep investor attention, many generalist FOFs have incorporated co-investments and secondaries into their mandates, potentially changing the nature of the exposure and the expected benefits for new investors. Our analysis suggests that certain specialties have greater potential for outperformance while others have yielded more mediocre results. Venture capital or emerging markets may make sense to target via an FOF, depending on investor resources and risk tolerance. Sources of value add are often found relating to access, scale, and specialization.

Theresa Sorrentino Hajer et al., “Venture Capital Disrupts Itself: Breaking the Concentration Curse,” Cambridge Associates Research Note, November 2015.

Although the myth that a small group of brand-name venture firms create most of the value was deflated by our 2015 paper, high-quality emerging and established venture funds alike can be difficult to access directly, and a skilled and well-networked venture capital FOF manager can help investors establish a high-quality and high-return-potential venture allocation. Our data indicate the median performance of US venture capital FOFs has consistently outperformed the median three-year rolling benchmarks for direct US venture capital funds.

Emerging markets FOFs are often attractive options for investors of any size lacking the familiarity, bandwidth, or resources to invest in these markets directly. Such funds can provide investors with ongoing exposure to these segments, or an opportunity to dip their toes in the market before eventually committing directly, and many managers of such funds are happy to educate LPs along the way.

Conclusion

Commitments to secondary funds are an effective instrument for all institutional investors seeking to increase exposure to private investments. Secondary fund commitments play a valuable role in nascent and mature portfolios alike, as they have favorable cash flow characteristics, provide diversification benefits, and offer investors good downside protection.

Selective commitments to FOFs in asset classes such as venture capital or emerging markets private equity are worth considering for investors not yet ready to invest in funds on a direct basis or those unable to gain direct access to their preferred general partners.

Andrea Auerbach, Managing Director

Alex Shivananda, Senior Investment Director

Other contributors to this note include Rich Carson, Rohan Dutt, TJ Scavone, Caryn Slotsky, and Christine Trang.

Footnotes

- Deferred payments are effectively seller loans that charge little to no interest. In this structure, the buyer may pay a portion of the agreed-upon purchase price at closing, and the remainder is paid over time. Though the manager has no legal obligation to do so, managers typically reserve capital required to meet future payments to avoid overinvesting the fund. Early portfolio distributions reduce the deferred payment ahead of schedule, freeing up the reserved LP capital for new investments. Managers can also employ third-party leverage to finance a portion of a secondary transaction.