Pension Schemes in Pursuit of Income, Growth, and Diversification

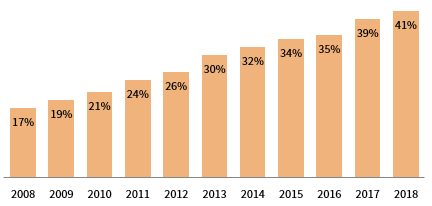

The UK Defined Benefit Pension Scheme universe is maturing, as more and more schemes have closed to future accrual (Figure 1). Funding levels have also generally improved over the past decade, aided by strong returns from growth assets and some liability hedging, which means sponsor contributions have fallen. We anticipate that many schemes are either cashflow negative or will be moving to a cashflow negative position very soon. 1 This will continue to cause problems in the current low-yield environment, where income is scarce.

FIGURE 1 PROPORTION OF UK DEFINED BENEFIT SCHEMES CLOSED TO FUTURE ACCRUAL

2008–18 • Percentage (%)

Source: Pension Protection Fund, The Purple Book, 2018.

Although schemes might be closing their Technical Provisions funding gaps, they still have a long way to go before reaching their secondary funding targets such as buy-out or self-sufficiency. Data from the PPF indicate that aggregate funding levels on a buy-out basis have increased from 60% to 73% over the ten-year period that ended in 2018. This means there is still a significant need for growth above liabilities, which presents its own challenge, given valuations are stretched and global economic conditions have weakened. We believe a new approach, which is more flexible and accesses compelling investment opportunities, can help trustees.

What is the industry doing to solve its current challenges?

In response to the income problem, many trustees are considering cashflow-driven investment (CDI) strategies. Such strategies rely on income from sovereign and corporate credit as well as on high-accuracy cashflow modeling to match benefit payments with income. While this may be appropriate for mature schemes with more predictable cashflows, we question whether these strategies are over-engineered. In other words, could CDI ultimately constrain trustees’ ability to meet their required return by relying too much on yield generation from a narrow set of strategies and assets?

A new approach to dealing with the issues faced by schemes today

A traditional approach to pension investment segregates the portfolio into return-seeking and matching buckets and then tries to incorporate liability-driven investment (LDI) and CDI within the matching bucket. We believe this may prove ineffective over the longer-term, especially given the problems highlighted earlier. Trustees should therefore consider an alternative ‘universal’ approach, which provides more flexibility, increases the drivers of income, and accesses more diversified risk premia.

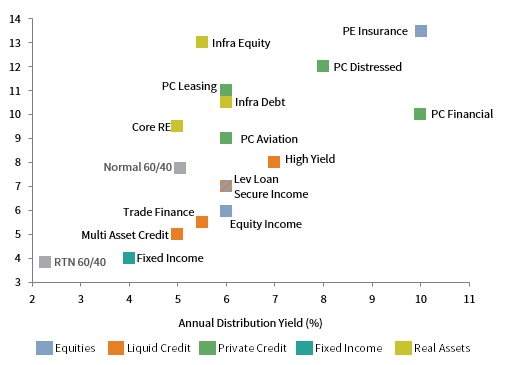

We believe this universal approach can help trustees generate sufficient income to exceed expected shorter-term cashflow needs so that there is less reliance on modeling accuracy. It also tolerates unexpected member experience, which can put pressure on liquidity. We achieve this by identifying managers that can deliver alpha above a market benchmark and by allocating capital to private investments that should allow schemes to access a premium above the public market (such as a diversifying private credit portfolio that includes real estate debt, royalties, leasing, and life settlements). Looking beyond traditional fixed income assets for income and return generation in the current environment is key if schemes want to be able to meet their objectives. And opportunities exist (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2 YIELD CAN BE FOUND, BUT IT REQUIRES LOOKING BEYOND

TRADITIONAL FIXED INCOME ASSETS

Total Returns (%)

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Notes: ‘RTN’ are Cambridge Associates’ projected returns under the Return to Normal scenario in which model inputs are assumed to mean revert over a ten-year period. ‘Normal’ are based on Cambridge Associates’ long-term equilibrium assumptions.

A universal portfolio can make full use of all potential sources of income. This may increase schemes’ ability to pay both planned and unplanned benefit payments, without needing the scheme to become a forced seller of growth assets. Considering income and growth sources holistically across the total portfolio means there is less reliance placed on one or two asset classes (or risk drivers) and can result in a truly diversified portfolio.

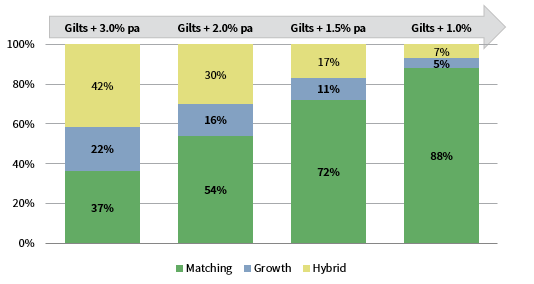

This approach can help trustees continue to take advantage of the most attractive opportunities from a risk-return perspective, and access the illiquidity premium, even as the scheme de-risks. Simplistically, it relies on three key building blocks:

- Matching Assets dampen funding level volatility and reduce risk across the total portfolio (through liability risk hedging) while also offering income and liquidity. Examples include UK government bonds and LDI.

- Growth Assets offer the highest expected return (and alpha potential) to increase a scheme’s ability to realise its required return whilst providing some non-contractual sources of income. Examples include public equity, private equity, and infrastructure equity.

- Hybrid Assets offer diversification by reducing sensitivity to equity risk while also offering a source of long-term income and growth potential. Examples include public credit, private credit, and core-plus real estate and infrastructure.

As schemes move along their de-risking journeys, the proportion invested in each of these asset class ‘buckets’ evolves (Figure 3). As funding improves, schemes will increase their allocation to matching assets (for hedging and liquidity needs) and gradually reduce their commitment pace to less-liquid (i.e., private) investments. These assets will naturally run off over time, generating growth and income. This contrasts to a traditional approach, which seeks to remove the illiquid exposure early on in the de-risking journey and miss out on the illiquidity premium. A truly diversified universal approach leverages a pension scheme’s biggest competitive advantage: Its long-term time horizon.

FIGURE 3 ILLUSTRATIVE PORTFOLIO COMPOSITION ALONG THE JOURNEY TO REACHING THE END-GAME

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Why do we think this universal approach is more effective?

- Uses capital efficiently: By adopting a holistic portfolio approach to liquidity planning, income can be mapped from several differentiated risk premia.

- Harnesses competitive advantage: Schemes can take full advantage of illiquid diversifiers over their long time horizon to generate growth and income.

- Matches inflation better: Incorporating a broader allocation to real assets provides an inflation-linked source of cashflow income while also benefitting from a differentiated return source.

- Offers additional flexibility: Schemes can capture new investment opportunities and access manager skill.

- Aids portfolio discipline: The universal approach reduces the need to disinvest from assets at inopportune times and mitigates behavioural risk such as short-term thinking.

- Access alpha potential: The greater allocation to high quality niche managers increases the potential for earning extra growth return through manager selection.

Won’t portfolio liquidity suffer with all these illiquid assets?

As schemes turn cashflow negative, it becomes more important to manage the schemes’ liquidity to ensure that assets generate sufficient income to cover cash outflows across all market conditions. Otherwise the trustees run the risk of being forced sellers of growth assets to meet benefit payments. Being forced to sell at the bottom of the market can hurt, so it is important to have a good understanding of the level of illiquidity in the portfolio. Therefore, trustees need to be comfortable that their income-generating assets will be able to generate sufficient income over the longer term.

Adopting a universal approach will largely mitigate this problem. A well-structured illiquid allocation can complement the liability hedging assets to comfortably manage outflows whilst maintaining the same liability hedge ratio. This portfolio would be more resilient even over extended periods of market stress.

Even in cases where buy-ins are planned along the de-risking journey, a significant proportion of active and deferred liabilities still have a long time horizon. This means there is still room for mature schemes to harvest the benefits of the illiquid investments.

Conclusion

UK pension schemes are faced with conflicting issues that are hard to balance effectively in the current climate. Trustees therefore need to carefully consider how to balance the need for income with required return objectives, all while maintaining an appropriate level of diversification to protect the scheme in a potential recession. We believe a traditional approach to portfolio construction can put schemes’ ability to meet their long-term goals, and members’ benefits, at risk.

Despite the industry’s efforts to introduce cashflow-driven investment as a new approach, we believe trustees need to be more innovative in their investment approach and take advantage of their still relatively long time horizon. A universal approach to portfolio construction can help schemes achieve required return targets whilst adding additional upside from alpha generation; reduce risk through true diversification; and generate sufficient income to comfortably meet both planned and unplanned cashflow needs. Collectively, these will help trustees be better equipped to achieve their long-term goals.

Rebecca Davis, CFA, Investment Director

Chris Powell, FIA CFA, Investment Director

Ferdinando Croce, Investment Analyst