Pathways to Sustainable Investing: Insights from Families and Peers

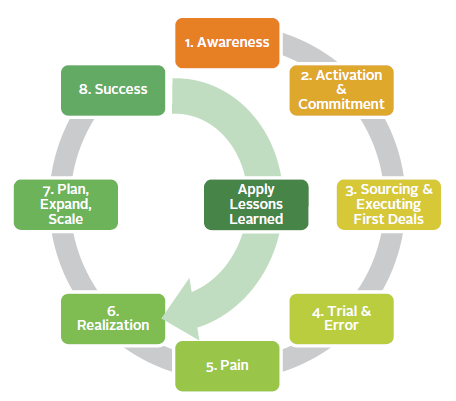

Every day, CREO and Cambridge Associates encounter wealth owners, families, and family office professionals who are starting down the path of sustainability investing. This paper details the typical path these investors take, the questions many of them face, and the way that many of them successfully develop a winning strategy that generates both returns and impact. Based on observations over the years, we have developed a framework to help investors understand where they are in the process. We describe this framework as the Sustainable Investor Path (SIP) Wheel; illustrate the strategies of several wealth owners, families, and family offices; and conclude with some lessons and best practices that investors can use to facilitate their sustainable investing journey.

Overall interest in sustainable investing is growing as many institutional investors and wealth owners re-evaluate their exposure to fossil fuels and as political discourse on climate risks builds. Wealth owners are at the forefront of the trend, driven by a long-term time horizon that is a natural match to sustainable investments, personal values, and interests expressed by next-generation members. As demand for sustainable investment opportunities grows, the market responds by increasing the supply of products. The current enthusiasm for sustainable investments represents a rebound of sorts for an area with a checkered history of ebullient promotion, but comparatively subdued successes. Therefore, prudent strategy and focused execution are critical to success.

The SIP Wheel synthesizes the accumulated experience and insights from numerous wealth owners and investment professionals working for single-family offices, several of whom CREO and Cambridge Associates interviewed for this paper. Their stories, told here together for the first time, offer several lessons for newcomers to the space, which can be distilled to the following:

- REMEMBER THERE IS A PATH. Knowing that many successful investors have traveled the sustainable investing path and overcome pain points can help maintain momentum.

- DERIVE VALUE FROM EARLY EFFORTS. Early investments allow wealth owners and professionals to gain pattern recognition and an opportunity to reflect on aspects of impact that are unique to sustainable investing.

- CONNECT WITH PEERS. Working together provides access to lessons, strategies, ideas, deals, and partners, all of which should help enhance returns and impact.

- DO NOT RE-INVENT THE WHEEL. Several frameworks and toolkits already exist, and although they continue to evolve, there is no reason to create them de novo just because an investor is new to the space.

- REGULARLY REAFFIRM THE LEADERSHIP. Investment decision makers need regular ongoing affirmation of their long-term investing mandates so they avoid pressure to conform too closely to the market or execute too conservatively.

- DESIGN DURABLE STRATEGIES FROM THE BEGINNING. Conscious forethought about the future resilience of strategies will help them survive over the long term, and even outlive current principals and investment decision makers.

- CREATE VALUES-BASED TOUCHSTONES. Sustainable investing rests on a long-term values-based commitment to making a positive impact on our planet and people; values-based touchstones are just as important as strategic financial reviews.

Done well, the journey wealth owners and their teams take when they decide to focus on sustainable investing is more complex than simply adding a new asset class to the portfolio. Because it introduces impact, which is not straightforward to measure, it raises meaningful questions for wealth owners and requires new investment talents and tools. But tackling the complexity can be deeply rewarding, as demonstrated by the investor stories CREO and Cambridge Associates have gathered. This paper is meant to help educate others and serve as an invitation to join and grow the sustainable investing community, one success story at a time.

Sustainable Investing Growth and Evolution

There is no denying that sustainable investing is a rapidly growing practice. According to an October 2017 McKinsey report, 1 sustainable investments constituted 26% of the $88 trillion in professionally managed assets in Asia, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Europe, and the United States. Moreover, managed assets with ESG (environmental, social, governance) integration have been growing at 17% per year.

Similarly, Cambridge Associates saw its client assets placed in ESG investments, including climate and sustainability funds, more than double between 2012 and 2017. More than 130 of Cambridge Associates’ clients, including endowments & foundations, pensions, and families, have already invested in some type of sustainable investment strategy. Cambridge Associates also sees more of its clients—especially families, and endowments & foundations—but also a growing number of pensions, asking questions about sustainable investing, with many building market-rate portfolios focused on climate and sustainability. CREO, for its part, has seen increasing enthusiasm from families, as well as single- and multi-family offices, in learning how to develop and execute a sustainable investment strategy. CREO has also seen its mostly US membership continue to grow since its inception in 2011, and has enjoyed increasing interest by global wealth owners and families since 2017. There is a myriad of data points to suggest future growth will continue to be meaningful, with most estimating it will be around 15%–20% per year.

There Are Multiple Drivers for this Growth

First, awareness of climate risks and resource vulnerability are increasing. Within the context of policy makers’ limited progress in addressing climate change globally, motivated investors are embracing market-driven mechanisms to accelerate the transition to a lower-carbon economy. Relatedly, some wealth owners feel a growing sense of urgency given the highly visible extreme weather events in recent years. This concern was amplified by a recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, 2 which warned that there are only a dozen years for global warming to be kept at a maximum of 1.5 degrees Celsius, beyond which extreme weather can negatively affect the lives of hundreds of millions of people. These dire consequences are echoed by the most recent World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report, 3 which suggested that “over a ten-year horizon, extreme weather and climate-change policy failures are seen as the gravest threats.” Many forward-looking wealth owners, thinking about the well being of their posterity and/or future-generation beneficiaries, are motivated to invest in climate solutions.

Second, volatility in traditional fossil-heavy commodities and natural resources equities are leading some wealth owners to revisit their investment approach. With or without a specific sustainability lens, they are evaluating renewables and resource efficiency opportunities as a potential long-term diversifier, cash flow generative asset, and growth sector. This is based on their underlying supply/demand fundamentals, shifting cost structures, and technological transition.

Third, political pressure is intensifying as the impact of climate change is becoming more evident to communities. For example, mainstream national political candidates in the United States, especially in more progressive communities but increasingly also in more conservative environments, are proposing policy solutions to address climate change as impacts visibly accelerate (e.g., flooding in the Midwest). While policy solutions may differ substantially throughout the political system, pressure is growing on the government to address climate change. Regardless of what happens at the electoral level in November 2020, we expect climate to be a key part of the national debate, compelling wealth owners to keep the issue top of mind when building and managing portfolios.

Finally, we observe that many next-generation family members and stakeholders simply care about climate and sustainability. Many are successful because their investment acumen and fluency in the topic are becoming more developed. This increased sophistication is enhanced by credible investor-speakers at investment conferences, some of which are profiled in this paper. Similarly, educational programs like the “Impact Investing for the Next Generation” program at Harvard University are helping these next-generation family members develop fluency, confidence, and networks. They also have more models to follow and point to, with some larger prestigious foundations providing credible pathways to start their families’ sustainable investing programs.

Economics 101: Supply & Demand

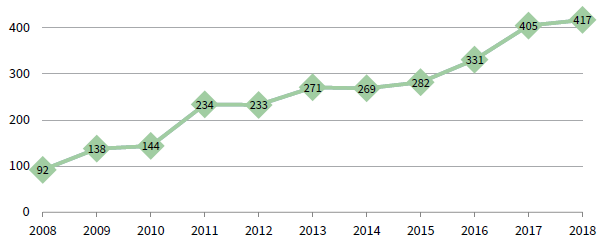

The sustainable investment marketplace appears to be behaving as basic economics would predict. Supply is increasing to meet the growing demand for sustainable investment opportunities. For example, Cambridge Associates is tracking more than 400 private market sustainable institutional investment managers, compared to fewer than 100 ten years ago.

NUMBER OF PRIVATE MARKET SUSTAINABLE INSTITUTIONAL INVESTMENT MANAGERS TRACKED BY CAMBRIDGE ASSOCIATES

2008–18

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Notwithstanding the increase in supply, constructing a high-quality portfolio of climate and sustainable investments can trip up even the most sophisticated wealth owners, which helps explain some the dynamics on the Sustainable Investor Path (SIP) Wheel described later.

The Rebound of the Sector

Investing successfully is difficult, and sustainable investing is no different. Many smart and well-intentioned investors, even those who are experienced asset owners and family office professionals, have gone through pain and learned valuable lessons. Investing best practices may sound intuitive, but consistently adhering to them is no easy task, particularly in an environment of shifting market conditions and ever-tempting behavioral biases.

Skeptics of sustainable investing often point to the historical underperformance of the cleantech sector. Indeed, many prominent investors “lost their shirts” in the 2000s cleantech wave, as one interviewee recounts. Yet, the appeal of cleantech venture capital in the mid-2000s was understandable. Some of the best known and successful venture capital firms in the world were moving into this sector; oil prices were rising, thereby making alternative fuels more economically attractive, and the policy landscape was appearing to favor cleantech. In fact, for some time there seemed to be bipartisan US congressional support for a cap-and-trade carbon policy.

But that chapter ended poorly for several reasons, including the global financial crisis, the shale boom, the race to the bottom in solar panel pricing, and the deterioration of policy support. But there were also specific investment red flags that were noteworthy and perhaps avoidable. Most venture capitalists in cleantech were not experts in energy or utilities; many were pivoting from other sectors such as telecom, semiconductors, or healthcare, which were out of favor at the time. Some firms employed relatively inexperienced professionals to lead cleantech investment activities. The demand pull for clean energy from the market, which was needed to optimize operating models, did not materialize as expected. Venture capitalists were consequently left without robust merger & acquisition activity to underpin the reliability of their exits. And perhaps most importantly, many firms used the venture capital model to back capital-intensive projects where the underlying technologies were still unproven at scale.

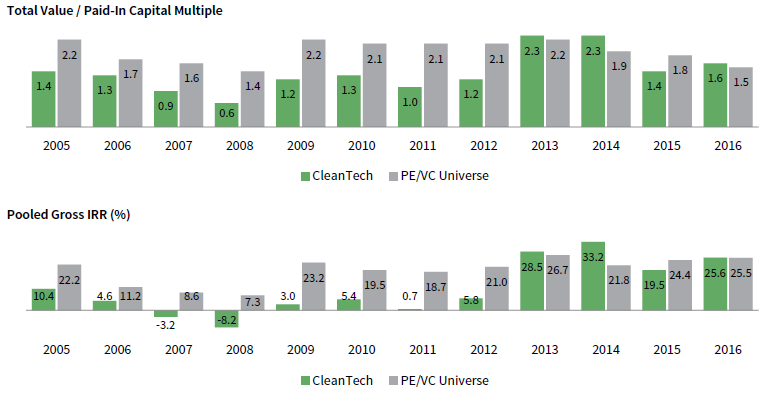

The sector’s returns from 2005 to 2009 disappointed, with gross-of-fee pooled internal rates of return (IRRs) of -0.8% according to Cambridge Associates data as of September 30, 2018. That said, cleantech companies receiving initial investments in 2010–16 generated a 13.4% gross-of-fee pooled IRR, with three out of four subsector groups returning more than a 15% gross-of-fee IRR. In fact, in several of the more recent calendar year cohorts, performance is looking quite strong, both on an absolute and relative basis compared to the broader PE/VC universe.

COMPANY ANALYSIS BY YEAR OF INITIAL INVESTMENT

As of September 30, 2018

Source: Cambridge Associates Private Investments Database.

Performance includes 1,352 investments and reflects gross deal level returns from 2005 to 2016. These investments comprise all company-level investments made by private equity and venture capital partnerships assessed as eligible for the CA Clean Tech Company Performance Statistics. As of September 2018, Cambridge Associates (CA) screened 81,248 investments held by 7,514 funds to identify cleantech investments. CA includes companies and projects in the cleantech sector if they (1) develop non-fossil fuel energy sources, (2) promote industrial efficiency by conserving resources and replacing existing processes with less-polluting alternatives, (3) recycle waste efficiently, or (4) provide a product or service that creates an environmental improvement. The full report is published quarterly and can be found at https://www.cambridgeassociates.com/private-investment-benchmarks/.

What caused the rebound? First, less capital has been chasing deals in the sector, and those firms that remain are much more cautious, phasing in capital based on operating milestones, as the venture capital model is supposed to be applied. Capital efficiency and unit economics became priorities, and there is generally less reliance on governmental subsidies or policy support to make the companies viable. In this new cleantech era, startup companies are intelligently integrating hardware and software solutions, and applying business model innovations to accelerate traditionally slow sales cycles. Hardware components in wind, solar, and energy storage have been dropping precipitously in cost, making renewable electricity generation cost competitive with traditional fossil fuel generation. Industrial energy efficiency applications have also benefited from declining costs due to scaled production of components used in other industries, such as consumer electronics and machine vision. Software costs have been driven down by the cloud and ever-increasing computing power.

These are some of the market conditions that sustainable investors are seeing today. While they are more favorable in many ways, there are still reasons to be cautious, given the late-cycle dynamics of the broader global economy. Prudent investors must maintain discipline, take a long-term view, and not lose sight of the fact that investing is a continuous learning curve. Those starting on the path today will be well-advised to connect with investors who have internalized prior learnings.

The Sustainable Investment Path (SIP) Wheel

Over time, no matter what type of wealth owner or family, a typical path has developed that creates a virtuous cycle, allowing investors to learn, reach some successes, and catalyze more follow-on capital into the space. This path is one of knowledge growth, learning, and doing. Though individual experiences may appear different, enough wealth owners have traversed the path that clear steps have emerged. The experiences of several different wealth owners inform the SIP Wheel.

SUSTAINABLE INVESTMENT PATH WHEEL

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC and CREO Family Office Syndicate Inc.

Step 1: Awareness

The pathway into sustainable investing starts with awareness. The observations driving awareness are unique to each wealth owner or family. For some, it comes simply from a human connection to the natural world around them. For instance, Raoul Slavin Julia of Treehouse Investments attributes his awareness to growing up in resource-scarce Puerto Rico. He says, “Puerto Rico depends on the rest of the world for everything. We’re a three- or four-day embargo away from running out of food and energy.” The combination of his geography with his personality as “a bit of science geek” led him to build awareness over time through reading and asking questions like, “How can I make my ecological footprint smaller?” The matriarch (the late Caroline “Polly” Keller Winter) of Temple Fennell’s family, a founder of the oil & gas business that amassed the family wealth, instilled good citizenship and stewardship of the community and the planet as family values. The family’s 3,500-acre farm in Louisiana provided a connection to the natural world and an opportunity for the family to reflect on its identity and values. That farm remains a central investment of the family office.

For larger, multi-generational families, a collective awareness may grow over time as more and more family members—often prodded by younger generations—inject their personal environmental connection into the family wealth management apparatus. The Laird Norton family, with roots in Minnesota and the US Pacific Northwest timber industries and around 500 members spanning four generations, became increasingly aware as a growing number of family members started asking their professional managers about sustainability in the 2010–12 time frame. Over the course of a few years, the family reached a consensus to bring sustainability to its investment approach.

For others, awareness about sustainable investing comes from adjacency. Before shifting toward an ESG investment strategy and founding Inherent Group, Tony Davis always had an interest in protecting the environment, and he had become involved in education reform and advocacy outside of his more traditional investment management role. When he decided to move on from that role to start Inherent Group, his experience helped him realize that ESG factors play a key role in long-term value creation. In turn, that led him to focus on sustainable investing. Marie Eriksson, an owner of Stena Corp, was trained as a lawyer and anticipated working on human rights. Under the auspices of the World Economic Forum, she convened a community of family-owned business leaders. Thinking about the purpose of that community, she recognized that many of the conversations were about sustainability, which led her to believe there was real opportunity in changing business operations and “investing for good.” Jeremy Grantham was originally interested in the relationship between land prices and economic growth. Seeking exposure to land as an investment brought him to forestry. Coupled with experiences his son had traveling in Paraguay, Grantham quickly recognized that tropical forests were pressured by loss of biodiversity and climate change. This prompted him to support a couple of major NGOs protecting forests and birds philanthropically. Over time, climate change demanded his attention because “the more you study it, the more desperate the situation seems.” As his interest grew, he helped sponsor two climate-focused academic institutes in the United Kingdom and one in India.

More generally, philanthropy was a part of awareness building for nearly every wealth owner interviewed for this paper. For some, like the Laird Norton family, the expectation was originally that environmental work would be part of the foundation rather than the investment office; in-house investment professionals now help the family members delineate ideas for which philanthropic capital can be more powerful than investment. The philanthropic work can also be more personal and direct. For nearly a decade prior to launching a sustainable assets fund, Reuben Munger pursued grantmaking to environmental NGOs as part of a growing desire to learn from others in the space. Eventually, he came to believe he could have a more meaningful effect via capital markets than through philanthropy. Nat Simons joined his father’s investment firm, Renaissance Technologies, in the 1990s, eventually spinning out and running the Meritage Group. He got involved in philanthropy in 2006, after seeing scientist (and later White House science advisor) John Holdren speak about climate on a local university campus. At a major philanthropic gathering shortly after, it struck him that philanthropists scarcely mentioned climate and clean energy. He saw major capital gaps on both the philanthropic and the private investment side. Simons maintains an emphasis on philanthropy and policy in addition to his climate-related investing and separates them into two related but differentiated categories. The low-carbon economy is an investment theme, and the fund in which Simons’ family’s philanthropic entities are limited partners has a returns-driven focus within that theme. Several other families have come to view investing as a major impact driver. One of the hallmarks of readiness to invest (not just donate) in sustainability was an awareness typified by one European wealth owner who said, “philanthropy just wasn’t enough.”

Step 2: Activation & Commitment

Once a family or individual develops some combination of sufficient aspiration and awareness, there is typically a trigger that activates commitment toward deploying capital. The trigger usually manifests as either an opportunity or frustration, but regardless of the form it takes, this stage is when an individual or a family decides “to do something,” as one wealth owner put it.

On the opportunity side, common activators include a family liquidity event, personal success creating capital and time, or even just an auspiciously timed investment opportunity. When Raoul Slavin Julia’s family generated liquidity through the sale of a substantial asset in 2004, there was an opportunity for him to put his time and capital toward climate investing. With encouragement from his family to pursue climate investing, he developed a wind energy portfolio together with his wife and sister-in-law. Reuben Munger had achieved success and personal wealth through professional investing, rising to the partner ranks within The Baupost Group. With that success in hand, he pivoted toward sustainability investing. When he saw a venture investment opportunity arising from one of the NGOs he was working with, he shifted his time and brought his capital toward it. Similarly, Tony Davis achieved enough success as a co-founder of Anchorage Capital Group to start a new firm, Inherent Group, and put his energy into executing an investment strategy where ESG plays a critical role in sourcing and underwriting potential investments. The Mulliez family, whose wealth was originally built through retailing in France in the mid-twentieth century and now spans across operating companies in multiple sectors, saw an opportunity to generate impact by getting people to eat better. Investing in sustainability across the entire food chain via Creadev, their evergreen investment firm, merged well-grounded convictions that there are serious environmental issues in agriculture and that obesity is a major public health issue together with a consumer trend toward healthier, more sustainable eating. Their operating companies gave them a vantage point from which to validate their observations.

One final type of opportunity is diversification. Reflecting on their values led Temple Fennell’s family, Keller Enterprises, to sustainable investing; they initially supported the wind developer industry that was struggling with volatility of the production tax credit (PTC). While thinking through the use cases of fossil fuels, Temple Fennell did a value-at-risk analysis that revealed the family wealth from oil & gas could be significantly impaired by the electrification of vehicles, carbon pricing, and the ongoing cost improvements in renewable energy technologies. The Keller family recognized that investing in wind might unlock a set of opportunities to hedge oil & gas ownership against future risks due to climate change, as well as allow them to be good stewards of the planet. Values led Fennell’s family to sustainability, but Fennell found a compelling financial opportunity well-suited to his family once he considered it.

Frustration can be just as powerful an activating force. For the Laird Norton family, a critical mass of family members became frustrated that a sustainability lens was not applied to investing. It had to be part of the business, not just a grant-making exercise in the foundation. While there were varying levels of sophistication among family members on financial matters, none would accept subpar returns; concessionary investments would not fly. This tension between their return expectations and their personal values—and the growing call for sustainable investments from shareholders—would drive the professional investment team to research new avenues and consider deals that previously would not have fit their mandate. Nat Simons was frustrated by the pace and scale of solutions for climate. To further the mission, he wanted strategic leverage any way he could get it, be it via philanthropic, political, or for-profit investments. New technologies and business models can change the carbon intensity of the economy, while delivering outsized returns to the investors. In 2009, Simons hired an investment manager to launch a low carbon investment practice, which led to the creation of Prelude Ventures in 2013. Simons’ family’s philanthropic entities are limited partners in Prelude, a venture capital firm focused exclusively on the low-carbon economy, managed by a general partnership of experienced venture investors.

Step 3: Sourcing & Executing First Deals

This is easily the least uniform step along the path. Making a personal commitment to invest can be empowering, but signing the first check may involve delving into family dynamics, convincing established advisors, finding new advisors, talking to experts, setting up new legal entities, reading, and then doing it all again—or not. It depends on the experience and temperament of the individual, the family, the source of capital, and the many relationships involved. One scenario is that a wealth owner will make the commitment to invest in sustainability, then follow a reputable contact or trusted friend into an upcoming deal hoping for the best. That happens and is perhaps even common. For instance, legendary investor Jeremy Grantham started out by simply co-investing in cleantech 1.0 deals with premier venture capital names. But our interviews suggest there is nuance at this step as varied as family offices themselves.

When France-based Creadev put their US investment team on the ground in New York a few years ago, there was already a strategy in place of diversifying investments out of the Mulliez family core retail sector and “empowering humans” mainly through healthcare, education, and renewable energy. But the United States brought challenges of high venture valuations and a complex and difficult healthcare system. Within renewable energy, Creadev saw specialist private equity firms with dedicated teams doing consistent deal volume in renewables and energy efficiency. Creadev eventually migrated toward food deals, just as some of the Mulliez-backed operating companies were surfacing new trends. But investing in the entire food chain, from production to new food to meal deliveries, was a new focus for Creadev. Delphine Descamps, Managing Director at Creadev, describes how they got comfortable enough to write a check: “We pulled together a focus group of 12, including family members, operating professionals, and the Creadev team. Over six months, we constructed a strategy by performing deep-dive research, consulting with experts, and embarking on a coast-to-coast US learning trip to better understand the food value chain. This allowed us to prioritize the segments we wanted to invest in.” They also sent a clear message that they were focusing on venture deals in food and agriculture in the United States, which differentiated them and brought them the targeted deal flow they sought.

For others we interviewed, moving from commitment to investment was easier. They identified a natural fit within sustainability investing by considering their existing knowledge and experience. Raoul Slavin Julia was part of a family that had generated wealth by investing in real estate that could be used by international manufacturers taking advantage of Puerto Rico’s tax inducements. He worked closely with a family team consisting of a lawyer, a CPA, and an engineer, all of whom had complementary skills and knowledge of asset acquisition and management. Slavin Julia settled on a strategy with some analogous attributes, and one that no else had tried: owning renewable energy assets in Puerto Rico. Tony Davis built his own wealth at Anchorage Capital Group managing hedged portfolios of value-oriented credit and equity investments. Convinced that the capital markets should reward financially material, positive social and environmental factors, he surveyed the landscape for funds that integrate these factors into their investment process. He found primarily long-only equity funds and exclusionary ESG funds that lagged the S&P 500 Index. In 2015, based on his observations, there were few, if any, options for investors interested in actively managed ESG-integrated strategies that invested long and short in credit and equity. So, he decided to create such a fund. Temple Fennell brought an understanding of tax equity structuring from experience in the music and film financing business and translated it into wind energy tax equity structuring. It helped that a former C-level business colleague had successfully built and sold a wind energy business; Fennell could rely on this colleague’s expertise to source deals for Keller and educate other family stakeholders.

Yet despite several stories of careful consideration between commitment and first check, that caricature of a wealth owner following acquaintances and friends in an investment can still be accurate. One wealth owner we interviewed admitted to quickly pursuing a sustainability-oriented investment based on relationships and without doing much diligence. Many companies continue to close financing from syndicates that consist almost entirely of a wealth owner and his or her friends.

Step 4: Trial & Error

“It’s fun at the beginning,” says one wealth owner a decade after starting sustainable investing. Without exception and regardless of the amount of preparation, the first investment for a wealth owner involves some trial and error, especially if the wealth owner or family office does not have prior experience with parallel investments in their traditional portfolio. Early investments mark a period of “learning by doing” where the educational dividend is large. Wealth owners at this stage almost always use a carve-out capital allocation, which is small relative to the broader portfolio. Multiple interviewees talked about allocations of a few million dollars. No matter the type of wealth owner, there is anecdotal evidence that he or she will start with seed or venture investments, given that these investments are viewed as more catalytic, involved, impactful, and measurable.

One US-based family office exemplifies a common experience. Having committed to climate investing, they started off by co-investing in early-stage deals using a very sector-focused strategy. They did not try to canvas everything across the spectrum of climate impact and renewable energy. Instead, they focused on animal agriculture and alternative proteins, which they determined could deliver significant climate impact. “It wasn’t super-technical, like fusion or semiconductors,” noted one of the family principals. Food products proved to be more understandable and relatable, and they could observe the consumer trends themselves. Their first investments were in syndicated venture deals for plant- and cellular-based meat alternatives.

Echoing a similar path, Reuben Munger describes the first investment he made into the space as a “relative one-off.” He had some extra time in 2007 because the markets were overpriced and his value- investing approach limited the number of interesting opportunities. At the time, he was particularly struck by the market dynamics around sustainable inputs and concluded that there were cost savings, opportunities for capital arbitrage, and financial returns available in removing gasoline from transportation. After he saw an idea in an NGO “that needed to be funded,” he dove in, did six months of diligence, and eventually made a venture investment in a company that was building a fuel-efficient line of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. The syndicate included Munger, an angel investor, an electric utility, and another family office. This investment occupied much of Munger’s time; he spent two years as Executive Chairman, followed by two years as CEO. Meanwhile, he also focused on grantmaking and did three more venture deals in 2009–10, followed by another six venture deals between 2011 and 2013. Munger says, “This was definitely a phase of learning and immersion.”

Trial and error can include breaking new ground. When Raoul Slavin Julia’s family decided to invest in wind for Puerto Rico in 2007, he started by buying a wind turbine secondhand from Europe—two turbines, plus a third for spare parts—without a place to put it up. “It was a leap in the dark,” he said. Slavin Julia spent a year trying to find a partner for a pilot project, a year marked by lots of confusion among potential partners about what he was trying to do. Some of the confusion was even sown by the local electric authority, which offered conflicting messages to site owners about interface with their grid. The first partner he landed was Bacardi, which was interested in onsite wind power for its distillery and could contract a power purchase agreement behind the meter. The Bacardi project broke even, and Slavin Julia suggests it might have even lost money if one were to account for the time he put in, but he learned a lot from it. Very quickly after that, Slavin Julia found he could get contracts for several other projects first in Puerto Rico and eventually beyond.

The trial and error step can create tensions between family members as real money goes out the door. One common source of tension is a difference among family members in the perceived importance and defined success of sustainable investing. The classic case is when part of the family wants to invest for impact, but the rest of the family is hesitant. The solution is usually a carve-out, but a side effect of this is that it increases the pressure on the family members who are doing impact to prove the strategy. THAT CARVE-OUT CAN BE PERCEIVED BY OTHERS AS A PASS/FAIL TEST, RATHER THAN A LEARNING VEHICLE. Multiple interviewees mentioned a longer-term aspiration to integrate sustainable investing within the broader family and that making an economic case for it is important. It makes the perceptual stakes high. As they themselves learn by doing, the family members most motivated by sustainability may simultaneously have to learn and teach their findings to other family members who may not have the time or inclination for impact investing. It is equally important to include the cost of learning into the success metric from the start.

Another source of family tension arises from strategy. In one family, discussions around venture investments raised differences of opinion about whether the family investment office should be pursuing that innovation or whether the family’s operating business should be incorporating it. When one branch of an American family with a successful history investing in oil & gas put together a presentation on impact investing for the broader family, it was not well received. It sparked a fear-like reaction and highlighted a wide gap in interest about sustainability. To avoid scaring the broader family with the sense that they wanted to convert all the investments to impact, in this case, the branch of the family realized that any movement toward a more thorough transition would need to be gradual and methodical. For example, this branch was able to convince the broader family to underwrite a solar development fund as part of its real asset strategy based solely on desirable risk, return, liquidity, and cash flow characteristics, without any impact consideration.

Step 5: Pain

It is common for new investors to encounter pain as they make early investments in impact, as in any area of investing. Systematically achieving an intended impact and financial return takes time and requires a lot of involvement. The track record of angels is poor. No experienced investor in the space claimed to get it right the first time and many bear the scars of their early efforts.

Occasionally, pain arises from new investors with enthusiastic, but flawed due diligence processes. There are multiple examples of impact funds that have gone through crises upon revelations about their authenticity, governance, or outright fraud. A European wealth owner described investing in a fund management company amid their fundraising process. The company was associated with several credible names and the wealth owner relied largely on their commitment and evaluation of the company. After investing, the wealth owner discovered that those individuals were not as involved with the company and that the management company was in a materially different financial position than initially understood. In contrast, prior to making a second investment—a direct venture-stage deal in water—this wealth owner carefully reviewed it, including speaking with multiple references on the technology, the team, and the customers.

Sometimes, pain is an unavoidable side effect of being a new entrant in the space. As Nat Simons tells it, “To establish yourself as a new player in the venture space is hard.” He founded Prelude in 2013, after he and his team were already making investments. In the wake of the financial crisis, investments in the low-carbon economy declined dramatically, but even then, competition was fierce for good deals led by experienced entrepreneurs. As a first-time fund, Prelude occasionally lost deals to more established funds. For example, it once lost a deal to a major name-brand Silicon Valley venture firm, even though that fund offered the company a term sheet at a 30% lower valuation. The lesson for Prelude: no matter the market, capital always competes for good deals led by strong entrepreneurs; experience, reputation, and track record still matter. Separately, in the mid-to-late 2000s, Jeremy Grantham was looking to invest alongside those name-brand firms, thinking they would do much of the heavy diligence work for him. “Nobody told me they would lose their shirts.” Grantham lost money and realized he would need to rethink how he pursued venture investing.

In other cases, pain arises from inherent characteristics of the investment, like the figurative thorn on a rose. Reuben Munger and Raoul Slavin Julia both miscalculated how the government might affect their early investments. Munger’s first investment (the hybrid automotive company spun out of an NGO in 2008) shut down in 2012, after waiting three years for a US DOE loan guarantee that never materialized. For Slavia Julia, starting in his backyard offered practical advantages, but he noted in the same breath that “Puerto Rico was the problem.” He found that he could readily get power purchase agreement contracts, but at the same time, the electric authority was creating permitting challenges or offering special discount grid-power pricing only to customers with whom Slavin Julia was working on renewable projects. “The lesson was don’t try to do something where the government doesn’t want you.” Investors may not be aware of government’s influence as a stakeholder in a given sustainability deal, a wrinkle that adds complexity to making capital decisions.

A refrain among many investors who shared their experiences with us was that they learned greatly from the pain.

Step 6: Realization

The path at this point can force a reckoning; sustainable investing is harder than originally expected. Some new investors feel the urge to cut and run. There is anecdotal evidence that when many new investors fail, they tend to flee the sector entirely. They also tell their friends. These stories, along with the well-reported failures during Cleantech 1.0 and later, can loom large. After all, there is no global database for sustainability investing across asset classes, meaning there is no easy way to analyze these stories quantitatively. Yet, in sustainability-oriented sectors, access to good deals largely depends on networking with trusted and aligned partners. The more a new investor does everything needed to succeed—build awareness, network vigorously, learn by doing—the more that investor will encounter stories of how investing in climate and sustainability proved harder than expected. In contrast to exiting the sector, many at this point reaffirmed their commitment to sustainability investing. Sensing an opportunity to expand or refine their investment theses, these investors have tended to change their strategy and correct course.

A combination of personal reflection and lessons from early trial and error helped Marie Eriksson settle on a path ahead in impact investing. After her stint at the World Economic Forum, she learned a lot from and was enthusiastic about some early investments from a capital carve-out, so she endeavored to launch a fund for her family. She pitched her family on creating a large technology-oriented impact fund, a gap she perceived in Europe. The family eventually committed a substantial sum to her fund and she spent three to four months in the Bay Area. She interviewed several dozen people to join her team and discovered it was hard to find people; the best talent wanted to start their own funds and/or be compensated like they had their own fund. Meanwhile, she was generating a significant amount of venture deal flow, reviewing around ten companies per day. She decided she didn’t want to do all this work herself and might have more of an impact if she allocated her time differently. Instead of doing direct deals, she has opted to focus on fund investments. As part of her work, she got to know fund managers well on a personal basis. Putting money into funds has allowed her the time to reflect upon investment ideas, ask questions, and really examine her level of trust in fund managers she has encountered. There remains room for co-investment with the funds into direct deals.

After the pain of his initial forays into sustainable venture capital, Jeremy Grantham set a new standard: if he was going to invest money in a green project and take the risk of losing capital, he would at least make sure it passes the test that “it will be important and very impactful.” If an investment passed that test and lost money, he could live with it. But if an investment was only “faintly green” to make money and he took a financial loss, that would be unacceptable. His strategy shifted toward real assets (thinking that would align him with Reuben Munger) and other investments that had different risk profiles from venture, potentially with more structure and downside protection. He also decided that he wanted to catalyze new teams, developing sustainable investment talent that could benefit the entire industry.

Laird Norton Company professional managers realized that they would need to expand their investment profile to meet the needs of the family. As a critical mass of shareholders drove the family enterprise toward sustainability around 2012, there was still an existing general investment strategy, namely investing in established operating businesses based in the US Northwest and investing $10 million–$50 million for stakes of 15%–80%. Much like Creadev found a few years later, Laird Norton Company executives had to contend with valuations that were driven very high. As Brian McGuigan, Laird Norton’s VP Investments, notes, “Laird Norton did not make venture capital investments. But around 2012, investing [in sustainability] meant young companies with less proven technologies and teams.” To meet the family’s demand to incorporate sustainability, McGuigan and his colleagues had to adapt their existing strategy and consider venture capital investments, if they still met the other criteria of the broader investment strategy.

Step 7: Plan, Expand, Scale

It is at this point along the path that a wealth owner starts to gain dividends from greater self-awareness, growing experience, and, sometimes, family interactions. It is the opportune time to introduce nuance, personalization, and new theses to an individual investment plan. Observationally, many experienced investors have at one point or another done an analytical deep dive to assess how they can best invest, and after an initial realization of the challenges of sustainable investing, it is a natural point to assess. Almost always, advisors, peers, family members, fund managers, limited partners, technical experts, and other stakeholders play roles in that exercise. At the same time, some wealth owners also revert to an exercise examining their values—again seeking peers and trusted confidants to help them refine their sustainability objectives.

By 2013, Reuben Munger had invested in ten venture deals, including the electric automotive company where he stepped into the CEO role; it had shut down after four years of operation, three of which were spent waiting for a government loan guarantee. At that point, he shifted out of his period of learning and immersion. He undertook a year-long systematic process with a close colleague to develop a new investment strategy in climate and sustainability. That process involved engaging a consulting firm, convening multiple offsite meetings, and drawing upon the knowledge of many experienced contacts. He concluded that his expertise interpreting financial market risk paired with an objective to bring in capital that would scale climate and sustainability impact with commensurate outsized financial returns. Much of the systematic analysis was devoted to specifying the resources, capital, and talent needed to meet that objective. Munger’s Vision Ridge Partners launched a sustainable asset fund in 2014. The investors in the initial close included himself, Jeremy Grantham, and another like-minded family office investor, but a broader set of investors followed and eventually capitalized the fund at $430 million.

Venture capital is still part of the strategy for some. Jeremy Grantham’s next phase of philanthropic and investment activity is focused on what he calls Neglected Climate Opportunities. It involves making early-stage deals in truly impactful and underfunded opportunities. In addition, he remains committed to US venture capital, seeing it as a mispriced asset in relationship to the rest of the US market. Whereas the other parts of the US capital ecosystem are suffering from sluggish growth and reduced R&D compared to the past, US-based venture capital is healthy. Thirty percent of his portfolio is committed to venture capital. Nat Simons continues to invest heavily in venture through Prelude. The Prelude team is now well known in the market and has a diverse portfolio of companies across the low-carbon economy in advanced energy, food and agriculture, transportation and logistics, advanced manufacturing and materials, and computing. Furthermore, Prelude has seen several exits, marking both a maturation of the fund and of the strategy. While Prelude is a long-term investor, it does not view itself as “patient capital”—rather it understands the time horizons for some hardware and materials focused companies. Nevertheless, it expects from its partners and delivers to its limited partners returns on par with other venture firms, on both a cash-on-cash and an IRR basis.

The pain of working in Puerto Rico prompted Raoul Slavin Julia to look beyond his backyard and led him to establish Treehouse Investments to invest globally. “It was scary at first,” he admitted. Slavin Julia knew he had to expand geographically and that he would need a team-based approach. “We knew there were certain things we could do directly, others where we could supervise teams, and still others where we would need to supervise those who supervise.” No longer just putting up wind turbines in Puerto Rico, it became essential to parse what they could do in-house, as well as trust and understand how others work. Treehouse’s core investment philosophy is scale, which in turn requires business sustainability. But Slavin Julia had learned enough about renewable energy and dealing with political risk that Treehouse felt comfortable putting money toward solar development in Kenya and mini-grids in Ghana in addition to the US-based wind assets that were a natural extension of Slavin Julia’s early steps in Puerto Rico.

Marie Eriksson relied heavily on personal reflection to help her organize a methodical investing strategy that could help move her family and their operating businesses toward sustainability leadership, while also allowing her to invest in opportunities that matched her personal vision without jeopardizing the assets or sensibilities of her family. She describes “a shift in thinking: Going from stewarding money for the family into stewarding money for the world.” Together with her family, she devised a structure that consisted of a larger pool of family capital that they would invest for financial return, as well as positive environmental and social impact, Formica Capital, and a second, smaller pool of her own money that she puts into “heart-centered” projects. Eriksson sits on the investment committee of Formica Capital and manages the venture part of the business, Formica Ventures. However, she spends the majority of her time on her own fund, Heartflow Ventures. Heartflow has an impact-first approach, supporting projects, people, technologies, and start-ups that Eriksson wants to see more of in the world. A big part of the fund is committed to creating spaces where people can experience inner transformation to expand their vision of conscious ways, enabling a world where people are more deeply connected with themselves, with each other, and with nature. Eriksson’s ultimate intention with Heartflow is to support a shift in global consciousness.

Six values at the heart of Temple Fennell’s family investment strategy are reaffirmed at every board meeting and annual family gathering. Though the strategy rests on family values, having a long time horizon and a network of trusted peers is a key differentiator. It was important for Fennell’s family early on to define a clear scope for sustainable investing that concentrated initially on large-scale wind and solar development and then sustainable agriculture. That focus kept the amount of capital and internal bandwidth well within the capacity of the family. Currently, there are three family members actively pursuing sustainable investments. By active choice, they do not employ any non-family investment professionals. Fennell prefers that family members make the investment decisions because most hired investment professionals expect compensation to be rewarded on one-year alpha, which Fennell sees as a mismatch with the family’s time horizon and may motivate passive resistance to particular deals. An investment strategy informed by values and that is understood by all family stakeholders, regardless of each individual’s investment engagement or expertise, allows the family to learn, plan and expand within a shared context. Combining sector-specific investment acumen with values-driven directionality underlies the subtle complexity for wealth owners investing in sustainability. Good information is critical to untangling the complexity. Peer networks and educational platforms like CREO, Prime Coalition, Confluence Philanthropy, and other like-minded reputable organizations, along with investment firms such as Cambridge Associates, are purposely helping to bring investors toward a much more methodical and institutionalized strategy. They strive to provide coherent approaches to designing and implementing an integrated portfolio that satisfies wealth owner needs while delivering financial returns with impact.

Step 8: Success

The final step along the path is success. With time, financial returns and impact start to trickle in, thereby generating more awareness and insights. In turn, investors gain new awareness (and a return of capital), which loops them back to the first step of the cycle.

If part of success is delivering results that draw more capital to sustainability, Reuben Munger and Vision Ridge are on track with their sustainable asset strategy. Critically, family office money provided much of the capital to Fund I for Vision Ridge, which provided a track record that foundations, endowments, and a pension fund needed to invest in a subsequent fund. In fact, most of their new investors committed purely on the economic value proposition, further validating the original financial thesis of the early investors. Building on initial investments by several family offices, Generate Capital, another project finance–oriented sustainable investment firm, raised $200 million in late 2017 to back battery storage and other distributed energy projects on smaller scales than traditional financing companies. 4 This fundraising success is in turn spurring the development of even more avenues for sustainable investing. A growing cohort of fund-of-funds designs, like The Low Carbon Cornerstone Fund, are proposing to aggregate specialist sustainable investing funds to help make institutional investment more accessible.

Finally, it is important as part of planning, scaling, and expanding to establish a definition of success. Any carve-out should have a risk-informed rate of return target. Though many wealth owners start with venture, ultimate success may not necessarily follow a venture capital model. Tony Davis’ firm, Inherent Group, for example, is focused primarily on the public markets, investing globally across the capital structure. A different model means that the financial metrics of success must be different. If the financial return metric is personal, the impact return metric is doubly so. At the same, several investors are seeking to influence corporate performance, either in public companies or their family businesses. Drawing in more capital—the way Reuben Munger has done—ranked highly as an ambition for many. As one investor said, “Success is world domination. The world is on fire and we are royally screwed if we don’t get this right.”

Coming Full Circle

Over time, wealth owners can expect to experience more and more success stories, but several give up as they travel the steps of trial and error. Yet, this is a virtuous cycle if completed. Families that “complete the circle” tend to be more aligned, become better investors, and can use valuable insights to kick off another cycle of insight, action, and capital deployment. Wealth owners can also minimize the negative impact of trial and error, and pain, by tapping into the insights of those wealth owners who have completed the circle already. Those insights offer wealth owners a shortcut for onward progress through the SIP Wheel, minimizing pain.

Learning from Trailblazers

A recent adage claims, “If you know one family office, you know…one family office.” Each wealth owner is different from the next, from legal structure and investment strategy to committee process. They also differ in their definitions of success, the intensity of their convictions or the breadth of their impact focus. Generalizing across such a varied population is hard, but there are some lessons that have emerged that are true far more often than they are not. Understanding these lessons can help investors move through the different stages of the SIP Wheel faster and minimize the pain and questioning stages of the journey. They are shortcuts—not necessary to bypass any one stage, but to progress more quickly and more effectively through the cycle.

Remember There Is a Path

Trying to deliver returns and impact at the same time is difficult, and investors can spend more time than others at different stages of the wheel. It is relatively easy to be overwhelmed at the options or disappointed at not meeting one’s own early expectations, especially since most investors are new at this. Knowing that most wealth owners went through a similar process, had similar moments of questioning and hesitation, made mistakes, but emerged on the other side with potentially successful, sustainable investment models can be very comforting to investors just starting to walk this path. Many wealth owners we have met over the years assumed that the roadblocks or questions they faced on their journey were unique, or that others had never faced the same dilemmas and setbacks. That belief can have its own set of negative consequences—dissention among stakeholders, doubts about the mission—and can even cause an investor to abandon the objective altogether.

This is particularly true because impact investing is still relatively novel. An investment in real estate that disappoints is usually filed away as a mistake with a lesson for an investor but may not cause him or her to question the asset class as a whole. AN INVESTMENT IN CLEAN ENERGY OR OTHER SUSTAINABLE SECTORS THAT DISAPPOINTS CAN CAUSE THE INVESTOR TO ABANDON THE SECTOR ALTOGETHER. Hence, the knowledge that most successful groups in the sector have gone through a full iteration (or more!) of the SIP Wheel, including the pain points, can be very important in maintaining momentum through the early sections of the Wheel.

Derive Value from Early Efforts

The early investments that a wealth owner makes (steps three to four through the first cycle of the SIP Wheel) are usually not the best ones. This can be true for almost any asset class, but the lack of experience with impact investing tends to make this worse. Nevertheless, early investments are crucial for several reasons. First, they allow the investor to build familiarity and pattern recognition in the space—a pre-condition for being able to sustainably generate returns. Second, they provide an opportunity to reflect on questions that tend to be unique to sustainable investing. For instance, did the investments provide the impact that the investor sought? What methodology does one use to measure the impact? How much time will this category of investments demand? Early investments allow investors to build a set of metrics and of vocabulary that will become increasingly useful and sophisticated as they progress through multiple iterations of the SIP Wheel.

There are two key variables that early efforts seem to materially influence. First, there is the definition of impact. Wealth owners start their journey with a definition of impact and of success that is usually well-crafted intellectually and that resonates emotionally. After a few investments, however, almost all investors review and refine these definitions, as well as their strategies more broadly. Realities, such as access to relevant deal flow, risk tolerance, structuring complexity, and growth potential, are difficult to assess without having made a few concrete investments.

Second, there is the wealth owner’s bandwidth itself (and closely related to this, the composition, expertise, and size of the team that will drive these investments). Again, prior to making some early investments, most investors allocate a certain amount of time and staff to these types of investments, but this often changes after actual deals are completed. For instance, some strategies emerge that are attractive but require more bandwidth.

Connect with Peers

One key lesson from wealth owners who have completed a cycle of the SIP Wheel is the need for connections to other like-minded investors. These connections are critical for several reasons. Mission-aligned wealth owners working together can share lessons learned to avoid repeating mistakes others have made. They can share investment opportunities, serve as sounding boards, and partner on key opportunities, usually resulting in better structures and more resilient companies. They can also share new ideas and develop innovative strategies that leverage their flexibility—family offices have pioneered approaches such as adapting traditional project finance approaches to earlier-stage companies, for example.

Connecting with other wealth owners and institutional investors does not just mean occasionally showing them deals and being on a first-name basis. For the connections to be meaningful and useful, there needs to be trust between the investors. Family offices tend to be more private than most other institutional investors by nature. But we observe that some of the wealth owners who are quickest to succeed in this space had building and maintaining a network of trusted peers as an explicit component of their strategy. They intentionally committed time and resources to do so. It is not easy to build, but a trusted network of aligned investors is one of the most powerful assets any investor can create over time.

Do Not Re-Invent the Wheel

The sustainable investing arena is attracting more and more investors. A wealth owner’s reflex may be to tackle this space with a strategy developed from scratch. Though this approach has its benefits, it is important to recognize that hundreds of wealth owners have been active in the space for several years, uncovering many lessons and best practices. There are useful frameworks available today to help wealth owners align their values with their investment strategy. For instance, the Sustainable Cycle of Investing Engagement (SCIE) 5 leverages a design thinking framework to specifically guide a family through a five-step process: establishing family values, framing strategy, developing strategy, implementing strategy, and communication and learning. Each step builds questions for wealth owners to grapple with, resulting in clear objectives the wealth owner expects to achieve. Within the “what” of the SIP Wheel, the SCIE provides a “how” for wealth owners just starting. It is a single example; connecting with others will expose families to other frameworks.

With common values and objectives established, wealth owners can then turn to proven investment models in various verticals that have generated both impact and financial returns. There are also allocation models that help shift capital over time from a standard portfolio to an impact portfolio. In other words, while the space is relatively new, there are many tools and lessons available so new entrants need not develop the basic tools de novo. This is especially true since focusing on impact investing has implications for the rest of the portfolio. Family offices are increasingly asked to be consistent; selecting some already-established tools and models can ensure consistency between a family’s wider wealth strategy and the impact investments.

Regularly Reaffirm the Leadership

In some cases, well-intentioned and well-structured efforts to invest in sustainability fall prey to conservative execution. Often, a new strategy proceeds too cautiously as those charged with executing it are concerned about career risk or embarrassment with family members or other decision makers when outcomes inevitably diverge from initial expectations. While this is the reality of working with those who are steeped in more traditional investment strategies and practices—or stakeholders new to fiduciary responsibilities—this challenge should not be underestimated. There are very few circumstances in which principal investment decision makers are making these decisions on their own. That means they are likely subject to internal and external pressure to revert to the norm, including reverting to a shorter-term performance time frame and more conventional sectoral interests. Beginning with an established stakeholder alignment tool, such as the SCIE framework, provides all investment decision makers the shared understanding to resist such pressures.

Market conforming behavior tends not to generate alpha in any investment strategy, regardless of sector. So far, outstanding performance using a sustainability strategy has tended to come from wealth owners who have provided clear goals to their investment teams and allowed investment decision makers to develop the execution strategy, take calculated risks, and not be subject to unnecessary hurdles driven by short term setbacks. Wealth owners that constantly affirm their long-term sustainable investing mandates, align structure and compensation with that mandate, preserve decision making independence, and consistently follow an investment process will create challenges at times with conventional forces. Investment decision makers in these sectors need implicit “career risk insurance” through these measures so that they are looking forward, rather than over their shoulders.

Design Durable Strategies from the Beginning

As wealth owners accumulate knowledge about sustainable investing, they reach a position where they can develop investment strategies with longer time horizons. When the timeframe grows, family member interest may wax or wane, investment professionals may change, market dynamics may evolve, science and technology will progress, and ideas about sustainability may shift. Conscious forethought to refine the right mix of structural flexibility and resilience can greatly enhance the overall durability of the strategy, and conveyance of the original intent. In practice, we have seen some common design features that enhance the durability over the long term. First, align compensation of managers, whether family members or outside professional investors, with both explicit financial and impact objectives. Second, insulate vehicles used to make sustainable investments from the wealth owner’s short-term financial, legal or operational dynamics to allow at least the time needed to assess the outcome of strategies. Those managing the investments should have the time and space needed to execute the strategy; at least seven, and often ten years is a benchmark. Third, very long-term strategies require structures that can outlive current family principals or key decision makers. One way to achieve this is spin out independent managers with families as anchor investors in funds, new general partners, and/or key governance input. Such a design has worked for CREO member Capricorn Investment Group, originally founded in 2000 by eBay executive Jeff Skoll. According to its public website, since 2014 “Capricorn has created multiple investment partnerships that manage more than $3.5 billion and focus on specific areas of impact or sustainability.”

Create Values-Based Touchstones

“Why are we doing this?” is a common question for the most effective investors in this sector. While long-term economic or business drivers stand behind their decision to invest sustainably, more of them are anchored in a commitment to make the world a better place for themselves, their children, and future generations. Their commitment derives from a sense of stewardship of the planet and people, as well as over their wealth and preservation of it. Although an economic thesis is crucial to an effective investment strategy, so is a long-term commitment to values. It is usually shared values rather than economic factors that bind families and teams together, create deeper connections with internal and external stakeholders, other wealth owners, and related investment teams, and ultimately make wealth owners feel fulfilled in meeting their own missions. The underlying passion that brings wealth owners to sustainable investing should be recognized and preserved through storytelling, mission statements, or other reconnections during generational change, roadblocks or other tough times. Investing in sustainability for multi-generational impact is a journey, not a destination.

Conclusion

Wealth owners all embark on a distinctive path when they invest in sustainability. Of course, investing in a new asset class, such as private equity, venture, or real estate, will involve a learning period. But impact investing is different: it cuts across all asset classes in the same way that risk and return does. It introduces the notion of impact, which is more difficult to measure than simply calculating financial returns. It raises questions that are deeply personal and meaningful for the families that sponsor them. It requires toolkits, including networks, expertise, and frameworks, different from those needed for assessing risk and return, and more difficult to build, in part because they need to be customized to reflect the theory of change and impact objective.

All of this makes the journey that wealth owners take when they decide to focus on sustainable and impact investments more complex than simply adding a new asset class to the portfolio. For most of them, that journey will include many of the steps highlighted in the SIP Wheel above. This may be concerning at first blush—beginning any process with a stage marked “pain” may be disconcerting to many. But as we have seen hundreds of investors progress in their journey, we have come to appreciate that all the stages of the SIP Wheel have value. They help investors focus their attention on building valuable networks, access the required knowledge, expertise and tools to build defensible investment theses that aim to generate successful impact and returns. It is not necessarily an easy journey, and folks who promise “easy” impact and sustainability investing success at no cost and no pain should be viewed skeptically. Learning how to do this well is not trivial—the lessons described above should hopefully help make the process easier—although still not easy. But Theodore Roosevelt said that “nothing in the world is worth having or worth doing unless it means effort, pain, difficulty.” We think that those same family offices that have emerged from their first or second cycle of the SIP Wheel would agree that this is a journey well worth taking. ■

An Invitation

This publication has presented several stories of wealth owners as they made their way through the SIP Wheel. This fast-growing community has more stories to tell. CREO and Cambridge Associates invite wealth owners to tell us—and other wealth owners investing in the space—their stories so that we can more quickly and more effectively grow the capital going toward sustainable investments. Join the conversation.

LEAD AUTHORS

Daniel Matross, Ph.D., CREO Syndicate

Liqian Ma, Cambridge Associates

AUTHORS

Christian Zabbal, CREO Syndicate

Régine Clément, CREO Syndicate

Tom Mitchell, Cambridge Associates

Jason Scott, CREO Syndicate

Rob Day, CREO Syndicate

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the wealth owners—named and anonymous—who contributed their stories. For providing information, review, and constructive feedback directly or indirectly, we also thank Michael Ellis, Lydia Thew, Gabriel Kra, Ramsay Ravenel, and four additional anonymous reviewers. We also acknowledge the contribution of Christie Zarkovich in helping to initiate this project.

About CREO

CREO, which stands for Clean, Renewable and Environmental Opportunities, is a NYC-based 501(c)3 public charity founded by wealth owners and family offices to address some of the most pressing environmental challenges of our time—climate change and resource scarcity. CREO delivers on its mission by catalyzing capital into innovative solutions to protect and preserve the environment and accelerate the transition to a more sustainable economy for the benefit of the public.

CREO works closely with a broad set of global stakeholders, including Members (wealth owners and family offices), Friends (aligned investors such as pension funds and university endowments), and Partners (government, not-for-profit organizations and academia) who collaboratively develop and invest in solutions across sectors, asset classes and geographies.

CREO activities include 1) capacity building by providing an expert and peer-to-peer educational platform where Members and other stakeholders can share applied knowledge and expertise, resources, and investment opportunities; 2) relationship building; 3) conducting research to support the advancement of its mission, and 4) providing deal flow as an extension of its educational program. For more information, please visit www.creosyndicate.org.

About Cambridge Associates

Cambridge Associates is a global investment firm that aims to help endowments & foundations, healthcare systems, pension plans, and private clients implement and manage custom investment portfolios to generate outperformance so they can maximize their impact on the world. With more than 45 years of institutional investing insights, the firm has helped to shape and implement investment best practices and built strong global investment networks with the purpose of driving outperformance for clients. Cambridge Associates delivers a range of services, including outsourced CIO, non-discretionary portfolio management, staff extension and alternative asset class mandates.

Cambridge Associates established a formal impact investing practice in 2008 to stay ahead of the increasing demand for top-tier investment ideas that align with clients’ missions and ESG priorities. The practice is now fully integrated with the firm’s global research and investment platform. Cambridge has more than 20 ESG/impact-focused investment professionals working across the platform, which includes research and investment teams, serving all core client segments, including endowments & foundations, private clients, and pensions.

Cambridge Associates maintains offices in Boston; Arlington, VA; Beijing; Dallas; London; Menlo Park, CA; New York; San Francisco; Singapore; and Sydney. Cambridge Associates consists of five global investment affiliates that are all under common ownership and control. For more information, please visit www.cambridgeassociates.com.

Footnotes

- Sara Bernow et al., “From ‘Why’ to ‘Why Not’: Sustainable Investing as the New Normal,” McKinsey, 2017.

- IPCC, 2017: “Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty” [V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, H. O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J. B. R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M. I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, T. Waterfield (eds.)], United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- World Economic Forum, “Global Risks Report: 14th Edition,” 2019.

- Brian Eckhouse, “Generate Capital Raises $200 million to Back Clean Energy,” Bloomberg, October 24, 2017.

- Kirby Rosplock, The Complete Direct Investing Handbook: A Guide for Family Offices, Qualified Purchasers, and Accredited Investors (New York: Bloomberg Press), 2017.