Outlook 2019: More Risk for Less Return?

In last year’s outlook we suggested that synchronizing global growth and healthy earnings projections (especially in the United States) seemed a benevolent backdrop for equity investors. We were far more cautious on sovereign bonds, given prospects for rate hikes and increased supply in the United States to fund growing deficits. As we go to press in early December, global equities are slightly in the red during 2018, and diversification plays including sovereign bonds and listed real assets have offered little consolation. Investors may be feeling a bit skittish as talk has shifted to rising rates, slowing economic growth, and growing geopolitical risks. A neutral allocation to equities still seems appropriate in 2019, but we acknowledge that risks are rising.

A key question for 2019 is whether this recent volatility marks an intermission of the nearly decade-long bull market or if it represents a turning point. We think the former, but the second act may be far shorter than the first. The US Fed is hiking rates and trimming its balance sheet, and other central banks seem poised to follow suit. Economic growth is slowing and desynchronizing across regions, even before the impacts of rising tariffs have been fully felt. Still, not all signals are discouraging. Equity valuations have improved in most regions and earnings growth expectations are not overly ambitious. Credit spreads have risen despite falling leverage and improving fundamentals, boosting the likelihood of higher returns. Central banks may change their tune should political worries start to bleed into hard data.

The following sections outline our views across asset classes and how we are weighing economic, political, and fundamental cross-currents against valuations. In developed equities, earnings growth and reasonable valuations (outside the United States) should bolster returns, though European stocks face rising political uncertainty and weak momentum. Despite rising macroeconomic headwinds and trade disputes between the United States and China, valuations still favor emerging markets stocks for investors with strong stomachs. Credit investors should look closely at opportunities in CLOs and bank capital securities. Sovereign bonds remain challenging, especially in the United States, given expected rate hikes while deficits increase and foreign demand wanes. Higher rates may not be enough to support the US dollar given stretched positioning and valuations, though a flight to safety would. Finally, we expect returns for many real assets to be muted in 2019, and remain focused on playing secular themes in both real estate and infrastructure.

While the continued presence of geopolitical risks and higher cash yields might suggest that investors reduce allocations to risk assets, we still think a roughly neutral allocation to risk is the right approach. That said, if we are right about prospects for future volatility, some of the laggards from this recent cycle (including active versus passive, and niche credit opportunities versus stocks) may finally have their day.

Wade O’Brien, Managing Director

Published December 10, 2018

Developed Markets Equities: Upside Potential, But Temper Expectations

While it’s extremely difficult to forecast one-year returns with any level of accuracy, developed markets equities should benefit in 2019 from starting dividend yields well above long-term averages outside the United States, slowing but still positive economic and per-share earnings growth expected across most markets, and continued robust US share buybacks stemming from the recent tax cut windfall. US equity valuations remain stretched despite the recent correction; with US profitability elevated relative to history and the business cycle looking long in the tooth, these rich valuations could be a headwind given expectations for further Fed tightening and higher interest rates. Valuations in most other markets are much more reasonable, but ongoing political risks in Europe and trade tensions with the United States could continue to weigh on developed ex US markets.

2018 in Brief: A Return to Divergence

Following a synchronized GDP acceleration across the major developed economies in 2017, global growth has been slowing this year and is no longer synchronized across the major economies. The US economy and corporate earnings grew at some of the highest rates of the cycle on the back of recent fiscal stimulus, including the sugar high of corporate tax cuts. Meanwhile, a cooling Chinese economy, trade uncertainty as a result of rising US protectionism and the United Kingdom’s impending Brexit, and tightening financial conditions all weighed on economic activity outside the United States. PMI 1 levels remain in expansion territory but have trended down in recent months, and the latest readings in the EMU and the United Kingdom are now below median levels of the past five years. PMIs for the United Kingdom are particularly subdued given uncertainty surrounding the prolonged and politically fraught Brexit process.

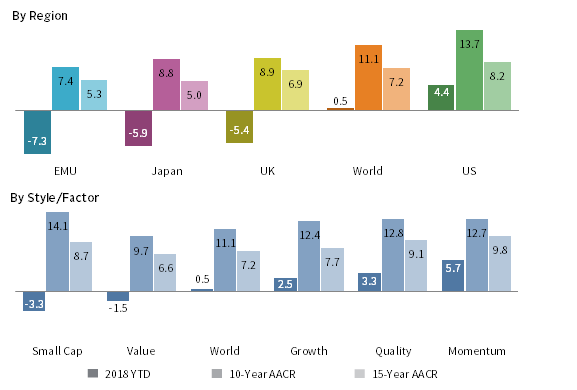

Developed markets equities (MSCI World 0.5% in local currency terms as of November 30) treaded water in 2018 after rallying 18.5% in 2017 and enjoying an 11.1% annualized gain over the last decade. Of the four major developed markets regions—the United States, EMU, United Kingdom, and Japan—all but the United States declined this year, consistent with the cycle-long trend of US outperformance but in contrast with 2017’s broad double-digit rally. The return dispersion across regions in 2018 was even wider in unhedged common currency terms given renewed USD strength.

Style and factor performance leadership in 2018 was also mostly consistent with the longer trends observed over the current cycle. Momentum, quality, and growth have continued to lead the way, with further gains year-to-date, whereas value—the perennial laggard this cycle—actually declined. Developed markets small caps are also down, but this result must be set in the context of small caps’ meaningful outperformance vis-à-vis large caps over the last two cycles. This year it appears that concerns about slowing growth, tightening liquidity conditions, and rising political and policy risk weighed on small caps due to their stretched valuations, more cyclical and less diversified revenues, and lower profit margins (primarily in the United States). As a result of the recent underperformance of small caps, ongoing struggle of value equities, and continued outperformance of high-priced growth and momentum stocks, 2018 was yet another year where headwinds to traditional active management (i.e., bottom-up stock picking) were mostly stronger than the tailwinds.

DEVELOPED MARKETS EQUITY PERFORMANCE BY REGION AND STYLE/FACTOR

As of November 30, 2018 • Local Currency • Percent (%)

Sources: MSCI Inc. and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: Total return data for all MSCI indexes are net of dividend taxes. Style/Factor indexes are based on the respective style or factor for the MSCI World Index.

Developed markets sector returns (not shown) are more difficult to generalize for 2018. The most common themes are the underperformance of financials, materials, and industrials and the outperformance of healthcare and utilities across major developed markets equity regions. Meanwhile, the relative performance of consumer staples, energy, real estate, and telecommunication services depended on the individual region or market. Information technology and consumer discretionary stocks significantly outperformed in the United States but meaningfully lagged outside the United States, though Europe’s far lower IT exposure meant the sector’s underperformance was only a relatively modest drag on absolute returns. These conflicting results reflect differences in the underlying industry composition of these sectors in US and non-US markets. Within the United States, the IT and consumer discretionary sectors—and, going forward, the rebranded communication services sector 2 —are much more tilted toward a handful of disruptive, very large, and highly profitable internet-driven businesses in contrast to those sectors in developed ex US markets. This has been one of the largest drivers of US and growth index outperformance this cycle, though technology stocks’ recent sharp correction may reflect the market beginning to question the sustainability of their superior margins and top-line growth.

2019 Outlook: Steady Dividends but Slowing EPS Growth and Uncertain Macro

Despite mixed results in 2018—including two sizeable corrections—the long post-GFC bull market cycle in developed markets equities has entered its tenth year. Now one of the longest on record, this cycle’s advanced age naturally begs the question of how much further it can continue. Our outlook for developed markets equities in 2019 is modestly constructive. Specifically, we believe the current bull market will continue at least another year, albeit with increasing volatility given tightening liquidity and rising economic uncertainty.

We maintain that equity bull markets do not die of old age alone—historically, the US economic cycle has driven the US equity cycle (which, in turn, has tended to drive the global equity market cycle). This dynamic may be even more likely next year, given that the US business cycle is well ahead of its developed markets peers. While the current US expansion is getting long in the tooth from a historical perspective, the post-crisis economic recovery has been unusually tepid due to household deleveraging, tighter financial regulations, and fiscal retrenchment (until recently). We acknowledge that US cyclical indicators suggest we are now in the later innings—the output gap has closed, the unemployment rate is historically low, and the yield curve has continued to flatten as the Fed normalizes its policy rate. Yet today there are few signs of excesses—aside from very elevated levels of non-financial corporate leverage as a result of a long period of historically low interest rates—that typically spell the end of business cycles.

In any case, absent an endogenous or exogenous shock, one predictive model for determining near-term US recession risk, based on the term spread between ten-year and three-month Treasury rates, currently suggests a roughly 16% probability of a downturn over the next 12 months, 3 signaling a slightly lower near-term recession risk than the unconditional probability of a recession occurring in any given year based on historical observations. 4 In the absence of this indicator suggesting an above-average risk of a near-term recession, we can look to the most recent trailing dividend yields and the prospects for 2019 EPS growth—these are important long-term equity return drivers—though one-year returns for equities can be heavily impacted by unpredictable factors, as we’ll discuss below.

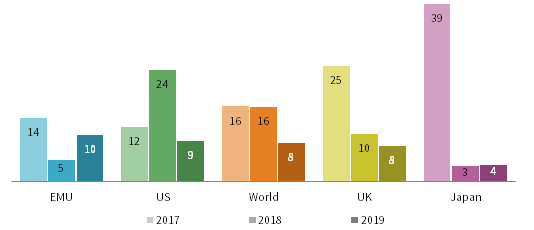

Sell-side analysts’ 2019 consensus EPS growth expectations are considerably more moderate than the mid-teens growth observed over the last two years. We may be on the backside of a cyclical peak, during which global earnings recovered from the China and US shale–driven commodity bear market and industrial mini-recession. US earnings growth also benefited this year from a one-time windfall as a result of substantial corporate tax cuts. We also must remind ourselves that “Street” analysts are perennially bullish: prior to 2017–18, developed markets’ realized EPS growth had consistently disappointed relative to consensus estimates coming into each year of the current cycle. Furthermore, the roughly 8% EPS growth currently estimated for developed markets equities in 2019 still meaningfully exceeds the actual trailing 15-year compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.5% and even more so the 5.6% realized CAGR since 1970. Assuming EPS growth reverts more toward these longer-term trends and setting aside any changes to price/earnings multiples, a combination of dividend yield and expected EPS growth on their own would suggest nominal total returns of 8%–9% for developed markets equities in 2019.Dividends are the most stable contributors to long-term equity total returns, and starting yields are a good approximation for the returns from dividend income over subsequent one-year periods. While the MSCI World’s current 2.5% yield is just below its long-term median, trailing dividend yields are actually well above average in all regions with the exception of the United States (2.0%). UK equities now yield 4.6%, more than double that of the United States, and EMU stocks currently offer a 3.5% yield. Even Japan (2.3%) now yields more than the United States, as a result of the Japanese market being out of favor and Japan’s progress on corporate governance reforms over six years of “Abenomics.”

CALENDAR YEAR CONSENSUS EPS GROWTH ESTIMATES

As of November 30, 2018 • Percent (%)

Sources: I/B/E/S, MSCI Inc. and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: EPS growth estimates data are updated weekly. MSCI World estimates are in USD terms and reflect the impact of currency fluctuations. All other regional estimates are in local currency terms. EPS data for Japan are for its fiscal year (April 1 to March 31).

The challenge with forecasting equity market returns over near-term horizons such as one year with any degree of accuracy is that unforeseeable economic, political, or social developments (and the sometimes irrational investor reactions they engender) can profoundly impact equity risk premiums in the short term. That said, we can look at recent levels and trends in valuations, fundamentals, and price momentum to get hints on what equity markets are currently pricing in.

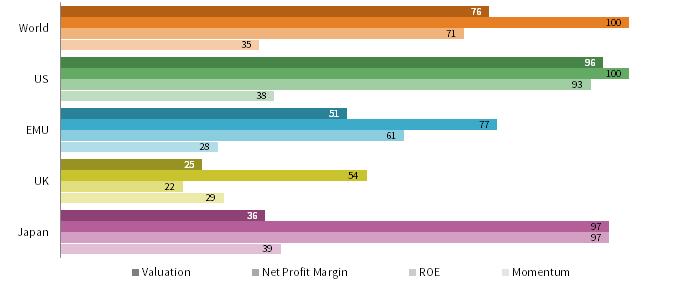

PERCENTILE RANKING OF VALUATION, PROFIT MARGIN, RETURN ON EQUITY, AND PRICE MOMENTUM

As of November 30, 2018 • Percentile (%)

Sources: I/B/E/S, Markit, MSCI Inc., and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: Percentile rankings are based on monthly observations beginning November 30, 2003, except for profit margin data, which begin on January 31, 2004. Valuation is based on the composite normalized P/E ratio for all markets except Japan, which is based on the ROE-adjusted P/E ratio. Profit margin data are calculated based on the IBES trailing 12-month weighted average sales per share and earnings per share. ROE is defined as the ratio of earnings per share to equity book value per share. Price momentum is the average of three-, nine-, 12-, 24-, and 30-month percentage changes in the index price level in local currency terms.

Valuations and profitability for most developed markets do not present significant headwinds. Following the recent correction, valuations across all developed markets are now below where they started the year, and developed ex US valuations are now effectively at or below historical medians. The main concerns are still-heady US valuations and near-record net profit margins in both the United States and Japan. However, both markets have benefited from corporate tax cuts and, relative to European equities, US and Japanese equities enjoy above average exposure to internet-driven technology, media, and telecom companies that have captured the lion’s share of economic rents in recent years. As mentioned, Japan’s government has also made a concerted effort to lean on the corporate sector to put its excess savings to better use in the economy, specifically targeting improvements in ROE with good success, though reform momentum has slowed considerably. Meanwhile, profit margins and ROE have steadily improved over the past two years across all regions as a result of the cyclical earnings rebound, though UK return on equity remains depressed relative to history due, in part, to outsized commodity exposure.

Share-price momentum is also not extreme in any major region, and has weakened as a result of the recent correction. Weak momentum is becoming an increasing headwind in Europe in light of ongoing political and economic uncertainty due to rising populism, the ongoing fits and starts of the Brexit process, and the recent showdown between Italy’s new government and the EU over the former’s spending plans. Price momentum is somewhat more supportive in the United States and Japan.

Summary

Despite known headwinds, the outlook for developed markets equities heading into 2019 appears moderately constructive overall. Absent unforeseen developments that affect global equity risk premiums, developed markets equities could generate positive mid- to high-single-digit total returns in 2019 based on expectations for stable dividend yields and slowing, but still respectable, earnings growth. The US business cycle is advanced, but risks of a near-term recession remain low. Global economic growth will remain supportive if it stabilizes near current levels, but a further slowdown would certainly present an additional headwind, with trade and political developments standing out as wildcards for the outlook. Share repurchase activity should also continue providing a modest boost to earnings growth on a per-share basis, particularly in the United States, where the recent record pace of buybacks should continue for another few quarters, as well as in Japan given record corporate cash balances and continued focus on governance improvements. Dividends should also continue growing at a healthy clip due to still decent free cash flow generation and better capital discipline. With EPS growth likely to slow from peak rates of the last two years, dividends should become a larger contributor to total returns next year.

For the most part, valuations remain supportive, particularly relative to overvalued bonds outside the United States; the main exception is stretched US equity multiples, which could succumb to a further back-up in interest rates. Price momentum is one signal flashing yellow as we enter 2019, especially in Europe, though again trends look marginally better in the United States and Japan. With the potential for trade tensions and political uncertainty to continue weighing on non-US markets, 2019 could be another year of US equity outperformance despite much higher starting valuations. UK equities are the dark horses going into next year, given quite undemanding valuations reflecting high economic uncertainty, middling fundamentals, poor sentiment, and weak momentum. All that said, if Prime Minister May can somehow shepherd her Brexit compromise with the EU through Parliament, UK assets could be off to the races, particularly more domestic-oriented mid-cap stocks, which would face fewer headwinds than large caps from the expected sterling rally associated with an orderly Brexit outcome. However, for developed ex US equities to outperform US equivalents in 2019, a further shift in market sentiment toward value stocks and away from growth and momentum stocks would need to occur. Such a scenario would also suggest a more conducive environment for traditional active managers to generate excess returns, as would a rebound in smaller stocks relative to large caps and a further rise in USD cash yields.

Emerging Markets Equities: Has the Gloom Gotten Ahead of the Fundamentals?

2018 was a difficult year for emerging markets equity investors. Returns were poor in the face of geopolitical challenges, many of which are likely to persist into 2019. We are concerned about the impact of tariffs, slowing Chinese growth, and continued Fed tightening (which pressures EM currencies). However, earnings growth remains respectable. Given reasonable valuations and supportive fundamentals, the medium- to long-term outlook is favorable, but the macro environment is likely to stir the volatility pot again in 2019.

2018 in Brief

In our 2018 outlook, we were mainly sanguine about the prospects for emerging markets equities, noting that macroeconomic conditions for emerging markets countries were favorable, as were valuations and earnings prospects. However, our report also highlighted the risk from more aggressive US trade policies, and we noted that if the Fed hiked rates this year at the aggressive pace that its own economists expected rather than the more measured pace that markets then implied, “that could goose the US dollar and negatively impact emerging markets shares and currencies.” We are frustrated to report that the exogenous risks we highlighted have more than outweighed the many positives we cited, 5 and emerging markets equities are on track to turn in a double-digit negative calendar year in USD terms, the thirteenth such result since the inception of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index in 1988.

Emerging markets equities returned -12.2% during the first 11 months of 2018 for an unhedged USD investor, with currency impacts driving about one-third of the decline. EM equities have declined 20% from their January peak levels, which is not a rare occurrence (over the past 21 years, investors in the asset class have experienced 16 declines of 20% or more). Euro-based and sterling-based investors fared better, with year-to-date returns of about -7% (their base currencies appreciated much more modestly versus the equity-weighted basket of emerging markets currencies). Unlike in the developed world, the sizable tech sector underperformed, 6 and value topped growth (however, as in the developed markets, small caps trailed large caps).

Looking Ahead to 2019

In 2019, some of the same macroeconomic factors that dimmed investor confidence in emerging markets will likely still be present. Tariffs could weigh on growth while boosting inflation, Chinese growth continues to slow, and the Fed is likely to continue boosting rates (perhaps lifting the dollar even higher). Emerging markets corporate fundamentals are not yet weakening: forecasters believe emerging markets companies will boost earnings by 10% next year, on top of this year’s expected 13% increase. Valuations, meanwhile (both of emerging markets equities and of their associated currencies), have improved amid this year’s declines.

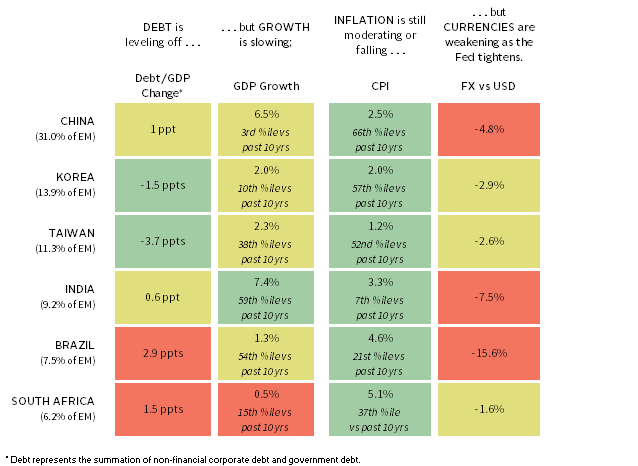

Macro Environment May Not Be Supportive

When we assessed the health of emerging markets economies in last year’s Outlook, we saw that governments were reining in debt growth without killing off economic growth, and that stable currencies and low inflation were allowing central banks to avoid growth-killing rate hikes. A year later, this narrative has evolved somewhat. Debt growth remains largely contained, but now economic growth is weakening, and four of the six largest emerging markets equity markets are growing at rates less than 2.5% (last year, only Brazil and South Africa were). Inflation is still in check, but with the average currency of these six countries depreciating 6% against the US dollar, rising inflation (and concomitant pressure on the country’s central bank to hike rates) could follow. If central banks feel the need to hike rates to defend their currencies or nip incipient inflation in the bud, that would whack growth and investor sentiment. We have not reached this point, but this is a medium-term risk.

MACROECONOMIC CONDITIONS FOR SELECTED EMERGING MARKETS COUNTRIES

As of November 30, 2018

Sources: Bank for International Settlements, Institute of International Finance, International Monetary Fund, MSCI Inc., National Sources, Oxford Economics, and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: All data represent year-over-year trend. Debt/GDP ratio data are as of second quarter 2018; GDP growth data are as of third quarter 2018. Consumer Price Index (CPI) data are as of October 31, 2018. Currency and policy rate data are as of November 30, 2018.

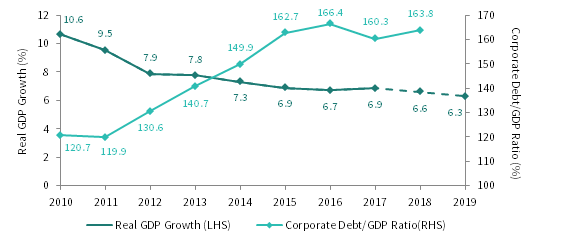

China’s government is having some success in its efforts to stem the expansion of the country’s debt mountain. Excesses from the borrowing binge that unfolded over much of the past ten years, however, pose continued risks. China’s corporate debt pile now totals some US$26 trillion (compared to about US$31 trillion for US corporations), after growing by 15% over the past two years. However, that is slower than the nominal growth of the Chinese economy. Chinese officials have been putting out one debt-fueled fire after another, moving from trust products and wealth-management products, to local government financing vehicles, to property-developer bonds. A year ago, China had no USD-denominated high-yield bonds trading at distressed levels, and now it has more than any other nation. 7 Most of China’s debt is held by Chinese investors rather than foreigners, and the Chinese government in all likelihood has sufficient resources and centralized control necessary to tamp down such fires before they spread. However, to the extent that China’s growth has been debt-fueled, will the government’s success at stemming debt growth prevent the economy from growing at a rapid pace?

Debt constraints are not the only factor limiting Chinese growth, however. Tariffs on more than US$250 billion in Chinese exports to the United States are likely to take a bite out of growth. 8 Barclays estimated that if the United States were to impose 20% tariffs on all Chinese goods imported into the United States, and the Chinese government were to respond proportionately, it would nick the US economy by 0.8% and Chinese GDP by 1.3%. This impact is not yet showing up in export stats: Chinese total exports rose 15.6% in October compared to a year ago (easily surpassing consensus expectations for 11% growth), and exports to the United States rose 13%. (The October data may still include the impact of some front-loading.) Regardless, a slowdown in Chinese exports to the United States will have very little direct impact on the firms in the MSCI China Index (only 2% of their revenue comes from exports to the United States).

Even before tariffs take a toll on the Chinese economy, deceleration stemming from the debt crackdown is evident: China’s real GDP grew 6.5% in the third quarter compared to the prior year, the smallest increase since the financial crisis, and a prominent government think tank estimates that next year, the economy will grow 6.3% (if the prediction is correct, this would be the slowest annual growth since 1990).

Regulatory risks are perennial in emerging markets, where roughly a quarter of the free-float market capitalization is allocated to state-owned enterprises. These markets are also vulnerable to tighter monetary policy, both homegrown (when local central banks boost rates to stem inflation or defend the currency, this constrains growth) and led by the largest developed markets central banks: Fed policymakers expect policy rates to continue perking up in 2019, 9 and this will place upward pressure on an already strong dollar.

CHINESE REAL GDP GROWTH AND CORPORATE DEBT-TO-GDP RATIO

2010–19

Sources: Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Institute of International Finance, National Bureau of Statistics of China, and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Notes: Real GDP growth for 2018 and 2019 are Chinese Academy of Social Sciences forecasts and represented by the dashed line. The corporate debt-to-GDP ratio is based on non-financial corporate debt. Corporate debt/GDP data for 2018 are as of second quarter. No forecasts of the corporate debt/GDP ratio are included.

Will Macro Malaise Continue to Swamp Fundamentals and Valuations?

Despite the clear challenges from tariffs, the Chinese government’s debt crackdown, and the Fed-enhanced US dollar, emerging markets fundamentals remain strong. At 12.4%, ROE for emerging markets index components is higher than it’s been in more than four years (and is considerably higher than the EAFE universe’s 10.9% ROE). Analysts collectively peg 2018 earnings growth at 13% and estimate that firms will grow earnings by another 10% next year. 10

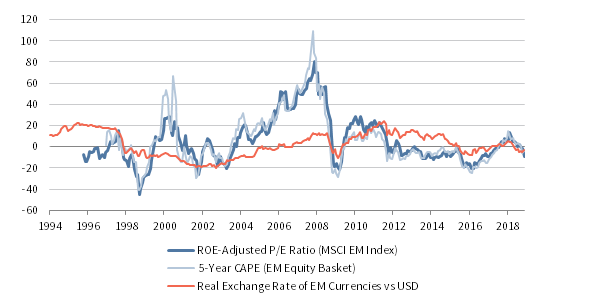

And valuations, which have much more influence on returns over long periods than short periods, are forgiving today after this year’s price declines. We evaluate the MSCI Emerging Markets Index according to its ROE-adjusted P/E ratio. That ratio is 7% below its historical median, and in the 30th percentile of historical observations. Secondarily, we try to eliminate the impact of changes in the index country mix over the years by calculating the CAPE ratio over the past two decades for today’s emerging markets country basket: the CAPE metric has been higher 58% of the time historically than it is today, where it trades at a 4% discount to the historical median CAPE. Emerging markets equities are also trading at a 33% discount to developed markets (measured by the two markets’ ROE-adjusted P/E ratios); this is deeper than the 28% historical median discount. And finally, we look at the real exchange rate of emerging markets currencies with the US dollar; that rate is at a 3% discount to its post-1994 median level.

VALUATION OF EM EQUITIES AND OF THEIR ASSOCIATED CURRENCIES

January 31, 1994 – November 30, 2018 • Percent Deviation from Median (%)

Sources: MSCI Inc. and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: The five-year CAPE is calculated for each country in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index today and then combined at today’s weights to create a historical valuation series. Valuation for emerging markets currencies uses the same countries and weights as in this EM equity basket.

Summary

In 2017, emerging markets equities could do no wrong. In 2018, they could do no right, and this had little to do with fundamentals. In 2019, some of the same macroeconomic influences could weigh on sentiment toward emerging markets assets. While emerging markets don’t appear vulnerable to a 1998-style debt crisis, the macro backdrop is not all that appealing. Economic growth is likely to continue slowing as the Chinese restrain the buildup of debt and as tariffs begin to bite. Currencies could face continued pressure from a Fed-emboldened dollar.

On the other hand, fundamentals at this point appear reasonable, and with a P/E multiple of just 13 and a nearly 3% dividend yield, emerging markets equities might not be all that sensitive to fluctuations in expected earnings. For investors that can stomach the considerable drama that this asset class metes out, we advise modestly overweighting both EM and developed ex US markets, underweighting the expensive US market. We believe that over the medium and long term, this posture will boost returns; however, if the overall environment for equities were to darken, the cheapness of emerging markets will not matter over shorter periods.

Sean McLaughlin, Head of the US Southeast & Mid-Atlantic Endowment & Foundation Practice

Credit: Challenges Remain

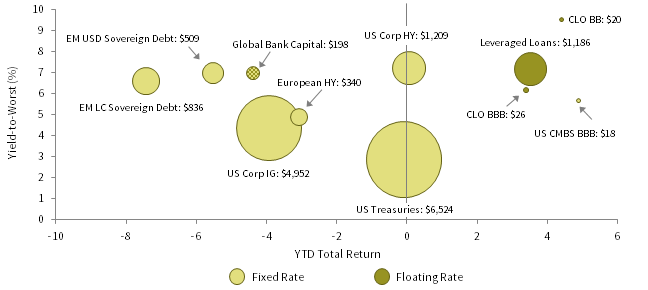

2018 was a lackluster year for many types of risk assets, and credit returns for the most part were no exception. Credit assets struggled amid choppy equity markets, rising interest rates, and a barrage of negative headlines warning over everything from weakening loan documents to rising fallen-angel risks. The late stage in the economic cycle elevates risks to credit investors, but these threats are well known. Spreads and yields are now more generous than at the start of 2018, offering some cushion if conditions deteriorate. Overall, our thoughts on relative value have not changed significantly: we still prefer structured credit (including CLO debt and equity) over more liquid markets, and floating-rate to fixed-rate exposures. Generally speaking we are more enthusiastic about private than public opportunities, though we are not enthused about the US$300 billion mound of dry powder in the former and suggest being especially selective in popular strategies such as direct lending.

2018 in Brief

Low yields and skinny spreads on many credit assets at the start of 2018 left them vulnerable to rising rates and macro uncertainty as the year unfolded. US high-yield bonds were basically flat in 2018 (0.1%) as yields rose more than 100 bps during the year. Leveraged loans (3.5%) easily bested high-yield bonds, a historically rare event and counterintuitive in a year of low defaults, helped by rising Libor and stable spreads. Investment-grade bonds generated a moderate loss (-3.9%) as yields rose to their highest level since 2010. Structured credit assets outperformed most of these more liquid alternatives, helped by higher starting spreads, floating-rate coupons (for many assets) and strong fundamentals in underlying exposures such as commercial and residential property. Hard currency emerging markets debt suffered given both rising rates and idiosyncratic problems for issuers including Argentina and Turkey; local currency emerging markets debt fared even worse in major currency terms as EM currencies plunged against the US dollar.

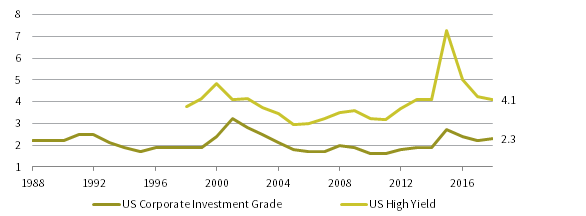

Concerns around fundamentals and market technicals also impacted credit performance. The US$5 trillion US corporate investment-grade market was affected by worries over the growing share of BBB-rated borrowers (now nearly 50% of the index), and whether the much smaller (US$1.2 trillion) US high-yield index might be able to absorb the impact if some of these bonds were downgraded by rating agencies and became “fallen angels.” The sheer volume of some of these BBB-rated credits presents concentration risks that may make a downgrade even harder to digest; for example, General Electric’s US$110 billion debt load alone is the equivalent of almost 10% of the US high-yield index. Meanwhile, leveraged credit investors fretted over (among other things) weakening loan documentation and what rising rates might mean for debt affordability. Lost amid the negative sentiment was that accelerating US economic growth and tax cuts meant fundamentals were improving. Leverage fell and interest coverage rose across the high-yield and investment-grade markets, despite some signs of more aggressive (read: acquisition-related) issuance.

DEBT MARKETS BY YIELD, PERFORMANCE, AND MARKET VALUE

As of November 30, 2018 • Local Currency

Sources: Bloomberg Index Services Limited, Credit Suisse, J.P. Morgan Securities, Inc., and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Notes: The area of each bubble represents the current market value of each index, shown in USD billions. Global Bank Capital are represented by the Bloomberg Barclays Global Contingent Capital Index, CLO BBB by the J.P. Morgan CLO BBB Index, CLO BB by the J.P. Morgan CLO BB Index, US CMBS BBB by the Bloomberg Barclays US CMBS Investment Grade Baa Index, US Corp IG by the Bloomberg Barclays US Corporate Investment Grade Index, EM LC Sovereign Debt by the J.P. Morgan GBI-EM Global Diversified Index, EM USD Sovereign Debt by the J.P. Morgan EMBI Global Diversified Index, European HY by the Bloomberg Barclays Pan European High Yield Index, Leveraged Loans by the Credit Suisse Leveraged Loan Index, US Corp HY by the Bloomberg Barclays US Corporate High Yield Index, and US Treasuries by the Bloomberg Barclays US Intermediate Treasury Index. Total returns data for EM LC Sovereign Debt are in USD terms. Yield for the Credit Suisse Leveraged Loan Index is calculated as the three-month LIBOR plus three-year discount rate.

What to Make of the Credit Wall of Worry in 2019

Markets will need to continue climbing this wall of worry if 2019 is to prove more fruitful. As central banks continue to roll back stimulus and the clock ticks ever later on this expansion cycle, focus is likely to shift to the timing of the next recession and related default cycle. The better news is that improved valuations on many credit instruments offer a bigger cushion than was the case 12 months ago. High-yield spreads are closer to fair value, and 7%+ yields should be better able to offset the impact if the Fed continues to tighten. Similarly, rising short-term rates should continue to lift coupons on leveraged loans, as well as those on structured finance instruments like non-Agency mortgage-backed bonds and CLO debt.

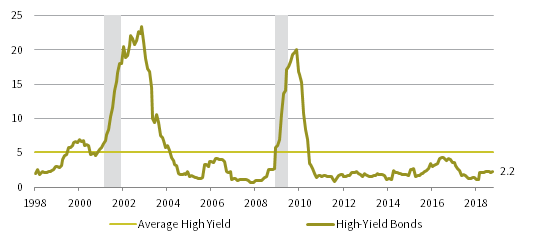

Some worries may prove overblown. Additional Fed hikes will mean interest costs increase for floating-rate borrowers, but this is coming off a low base; interest coverage for high-yield borrowers stands around 4.0 times, above the long-term average of 3.4 times. Given that the Fed’s pace of rate hikes would likely slow if economic conditions deteriorate, continued rate increases should also be accompanied by improving earnings. High-yield bonds have historically posted decent returns in periods when ten-year Treasury yields have risen 50 bps or more; over the past 20 years only two of these periods (during 2004 and 2005) were associated with negative returns for high-yield bonds.

NET LEVERAGE RATIOS: US CORP INVESTMENT-GRADE BONDS VS HIGH-YIELD BONDS

1988–2018

Sources: Bloomberg Index Services Limited and Intercontinental Exchange, Inc.

Notes: Data are annual. Data for US high-yield bonds begin in 1998. US corporate investment-grade and US high-yield net leverage data are calculated as net debt/trailing 12-month EBITDA for the Bloomberg Barclays US Corporate Investment Grade (ex Financials) Index and ICE BofAML US High Yield Master II Index, respectively. Data for 2018 are as of second quarter 2018.

Steady economic growth in the United States and other developed markets, even if slower than in 2018, also means a surge in defaults is unlikely. Spikes in defaults historically have occurred only after recessions have begun, as was the case in 2008–09 and before that 2001–03. The positive macro backdrop may mean distressed funds continue to struggle finding opportunities, and fewer secular themes (like retail in 2018) seem to stand out. Over-levered companies exist and some will provide idiosyncratic opportunities, but distressed specialists may need to look farther afield (including outside the United States) and avoid getting shorts wrong, given higher credit spreads.

US HIGH-YIELD DEFAULT RATES

January 31, 1998 – October 31, 2018 • Percent (%)

Sources: Deutsche Bank Securities Inc., Moody’s Investors Service, and National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

Notes: Data are monthly. Default rate data include distressed exchanges. Default rate data represent the trailing 12-month USD-weighted (par-weighted) default rate. Data prior to June 30, 2017, are represented by Moody’s default rates as provided by the Deutsche Bank US Credit Strategy Chartbook. All default rate data on and after June 30, 2017, are sourced from the Moody’s Investors Service Default Report. Shaded areas indicate NBER-defined recessions.

Credit bears may concede these points but warily eye weakening loan documents, the near-90% share of covenant-lite transactions, and other signs of late-cycle excess such as the increase in acquisition-related finance. These worries have merit. However, adverse economic conditions, which are not on the visible horizon, are much more typically associated with struggling corporate borrowers than looser documentation. Practical reasons help explain why some customs have changed in the leveraged loan market. Today’s loan borrowers are larger and more stable than historically has been the case. Twenty years ago, only 32% of the loan market consisted of deals larger than US$500 million; today 78% of loans exceed that amount. As the size of loans has increased, the practicality of enforcing covenants among a necessarily larger group of lenders has suffered. Weaker protections for borrowers are likely to lead to lower recoveries for investors when defaults do occur; this may be exacerbated for loan investors, given the rising share of loan-only borrowers. But, above-trend economic growth and reasonable leverage mean today’s low default rates are unlikely to change materially in the next several quarters.

What We Recommend

Investors would also do well to look at European CLO debt and equity, as well as some of the subordinated debt issued by Eurozone banks that has taken a drubbing in recent months. Euro-denominated contingent capital securities (so-called CoCos) typically have BB ratings. Yet, given weaker equity markets and concerns over certain issuers’ exposure to emerging markets, their current OAS of around 461 is well above that offered by comparably rated euro corporate bonds. USD-oriented investors that have the ability to currency hedge may find these types of lower-rated and high spread euro-denominated instruments attractive, given the current cross-currency basis swap (from euro back to US dollar) means they could pick up around 300 bps of additional yield.Investors should be selective with credit investments in 2019. Despite 2018’s repricing, some credit assets and strategies remain overvalued and may continue to generate low returns. US leveraged loans, which currently yield 7.2%, still seem attractive relative to high-yield bonds. The catch? In the next recession, not that we are necessarily forecasting one for 2019, loan recoveries will likely be lower than during prior downturns. Given higher spreads, structured credit remains more attractive than either, though the opportunity set is shrinking as legacy assets including non-Agency mortgage-backed bonds continue to pay down. CLO debt and equity offer exposure to leveraged loans, with an additional expected-return premium for their illiquidity and complexity. This premium can be substantial; for example, despite lower historical default rates, BB-rated CLO debt now offers yields over 9%; their 645 bp spread is about double the level of similarly rated high-yield bonds. CLO equity, which currently is accompanied by long-term debt that has been issued at attractive spreads, may offer attractive optionality if the credit cycle turns in the next couple of years. 11 Investors should implement only through skilled third-party managers 12 (charging reasonable fees) that have expertise both in analyzing the underlying loans in the structures, as well as familiarity with how individual CLO managers have performed through the cycle.

Private credit opportunities are harder to generalize about, as manager selection remains paramount. Strategies including royalties, leasing, and life settlements have higher barriers to entry than liquid credit and will continue to offer non-correlated return streams, as well as high current yields. These strategies seem to have attracted less capital than others like direct lending, where a capital overhang is growing and standards are slipping. As mentioned above, US-focused distressed strategies may also struggle to put capital to work. Conversely, the opportunity set may be growing for distressed and capital appreciation strategies focused in other regions. The US distressed ratio has fallen from 6% in January to less than 4% in September, but has quadrupled in emerging markets to more than 10%. China may be a key country for emerging markets distressed managers in 2019 given slowing growth and reduced credit availability. Some managers are targeting Chinese companies that can pledge offshore assets as collateral for loans, easing concerns over local bankruptcy proceedings. For investors that don’t want to lock up capital, rising yields on emerging markets high-yield bonds (which have risen 276 bps in 2018 to 8.60%) could make the asset class an increasingly fertile area for skilled credit pickers.

Summary

A year ago, we advised investors to be patient when investing in expensive liquid credit and seek out opportunities in structured credit and private funds, including those focused on real estate debt. Today spreads are higher across most instruments, reflecting rising risks. Aggressive practices in loan underwriting are becoming more pervasive and perhaps more importantly the backstop of central bank asset purchases is steadily dissipating. Structured credit remains attractive, though we are less constructive on picked-over real estate–backed bonds and more interested in CLO paper. As was the case in 2018, some of these assets/strategies may outperform equities next year, especially in fully priced markets like the United States. European equity valuations seem more reasonable but earnings growth looks threatened, thus select credit opportunities like bank capital may also compare favorably with stocks, especially on a risk-adjusted basis. Emerging markets debt has also significantly repriced, and attractive opportunities are being created for public and private funds. Other private strategies that remain of interest are capital appreciation funds, which would be well-placed if conditions suddenly shifted. Looking across other private credit opportunities, we note that nearly 200 managers were in the market with new direct-lending funds as the year came to a close—the returns on at least some of these are likely to disappoint.

Wade O’Brien, Managing Director

Real Assets: Shoring Up Defenses

Recent months have reminded investors that markets are volatile. As we enter 2019—a year in which markets may be forced to continue contending with slowing global growth, heightened geopolitical tensions, and tightening monetary policies—we see few reasons to expect a return to the subdued levels of volatility that characterized years past. Against this backdrop, and considering the richness of real estate markets, the uncertain outlook for commodity demand, and the amount of capital that has poured into infrastructure markets, we think real asset investors would be well served by focusing on managers and investments that are positioned to perform well through the business cycle.

To address these challenges, three tactics may help shore up portfolio defenses. First, investors should understand how current investments are thematically linked to secular trends, such as e-commerce growth and demographic shifts. Second, investors should rebalance to ensure portfolios hold diversified sources of risk, favoring investments more closely linked to secular trends than cyclical. Lastly, investors should consider favoring lower-risk, income-producing strategies when allocating additional capital. Within this context, we highlight the current state of major real asset markets and how they may evolve in 2019.

2018 in Brief

Public real assets delivered uninspiring returns in 2018. While investments in natural resources shined through much of the year, as tightening oil market conditions briefly pushed the price of Brent crude above US$85 per barrel, investment gains didn’t last. With data raising doubts about the state of the global economy and US crude production surprising to the upside, oil prices suffered a historic rout, prompting energy-linked investments to sell off. The Bloomberg Commodity Index, MSCI World Natural Resources Index, and Alerian MLP Index this year returned -4.7%, -8.9%, and -3.4% in unhedged USD terms, respectively.

Other real asset investment options fared better this year. Listed property and infrastructure companies suffered considerable setbacks in February, when volatility spiked across risk assets and forced prices lower. Not until mid-year had these securities climbed back into the black, aided by a softening in monetary policy expectations and their high-income nature. Ultimately, the FTSE NAREIT All Equity Index, the FTSE EPRA/NAREIT Developed Index, and the FTSE Developed Core Infrastructure 50/50 Index returned 4.2%, 0.7%, and 0.4% in unhedged USD terms, respectively.

Real Estate

Commercial real estate prices have risen substantially since the end of the GFC. One global benchmark indicates prices across all commercial real estate sectors are up by almost 50% since cratering at the end of 2009. While the benchmark’s performance does mask dispersion, many of the best-performing countries and sectors in real estate since 2009 were those hardest hit during the crisis. Nowhere is this truer than in the United States, where commercial real estate prices in aggregate are up roughly 90% and multifamily in particular are up more than 140%. Yet, in looking across different geographies and asset types, one thing appears clear—real estate is expensive and it is getting late in the cycle.

One way to judge the richness of a real estate market is to review the rates of return implied by that market’s expected income. This measure, which is known as the market’s capitalization rate or yield, suggests long-term returns are likely to be low for virtually all countries and sectors for which data exist. Consider that the latest aggregate US cap rate reading is just below 5%, which is the lowest level offered in four decades of data. A similar UK measure suggests yields are slightly below 6% and near their all-time low across three decades of data. In continental Europe and Asia, property yields aren’t telling a meaningfully different story.

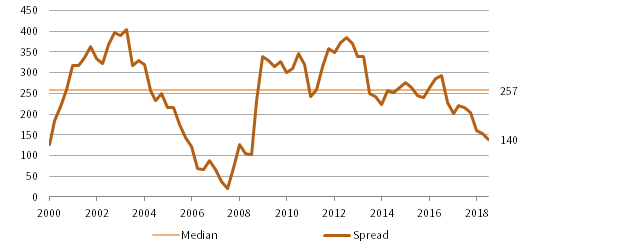

Today’s low cap rates suggest property values may be vulnerable. Indeed, price growth has slowed in some countries and sectors. In the United States, prices grew by just 4% over the last four quarters, down from a nearly 7% pace in 2016, as the Fed has tightened monetary policy. The reality has impacted the spread between cap rates and the yield on ten-year Treasuries. This spread, which represents a risk premium investors require of real estate, compressed to 140 bps by third quarter 2018, its lowest level in a decade and a far cry from the 257 bp cushion that US real estate has enjoyed on average since 2000.

US COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE CAP RATE SPREAD OVER 10-YEAR TREASURY YIELDS

First Quarter 2000 – Third Quarter 2018 • Basis Points

Sources: Federal Reserve, National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries, and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Note: The capitalization-rate spread over ten-year Treasuries represents the spread of the quarterly market value–based cap rate on the NCREIF Property Index over the quarterly average ten-year Treasury yield.

Still, commercial real estate fundamentals look reasonable. In general, construction has been moderate this cycle, limiting growth in supply and prompting vacancy rates to fall to low levels. But, in considering how far prices have come and the murky economic outlook, investors could soon require a greater real estate risk premium than the small spread currently demanded. If that happens, it would impact growth in real estate prices, if not undercut it altogether. Private high-income real estate strategies that exploit long-term secular trends, such as the need for last-mile logistics or healthcare, may best support real asset portfolios next year.

Natural Resources

Unlike real estate, natural resources investments have performed poorly this business cycle. A broad commodity futures index returned -19% since prices bottomed in early 2009. 13 Even natural resources companies, which can partly manage underlying commodity price volatility with hedges, returned only 60% across the same time period, underperforming developed markets equities by more than 170 ppts. This challenging environment has led many investors to question whether these investments even make sense in a broad portfolio setting. Yet, this poor performance is precisely why these investments shouldn’t be shunned.

Lackluster returns have meant valuations remain fair. Looking at long-term inflation-adjusted prices of a diversified commodity basket highlights that its current price is not substantially different from its historical record. Natural resources equities, which we prefer to commodity futures, trade at a reasonable 12x composite normalized earnings and look cheap relative to developed markets equities. What’s more, these firms are expected to grow next year—analysts are currently penciling in earnings growth of roughly 15% for natural resources equities, relative to 8% for developed markets equities as a whole—from their current low level of earnings.

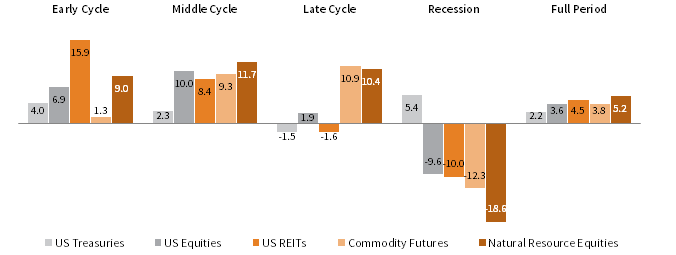

These investments have also tended to perform well as business cycles age. In reviewing the last six US business cycles that ended with the GFC, commodity futures and natural resources equities historically outperformed other major investment categories by considerable margins in late-cycle expansionary periods. These investments were helped by the fact that as business cycles aged, excess capacity tended to shrink. Shrinking supply prompted input costs, such as commodities or labor, to rise. However, as business cycles advanced from late-cycle to recessionary periods, both of these investments have tended to underperform.

A challenging aspect of natural resources investments is their high levels of volatility. Just a few months ago, concerns about the trajectory of global economic growth raised doubts about the future of commodity demand and triggered sell-offs in both commodity futures indexes and natural resources equities. Yet, the dramatic global drop in new well and mine investment, from nearly US$1 trillion in 2014 to less than US$600 billion today, suggests commodity markets shouldn’t be saturated by a jump in supplies. In our view, exposure to commodities—in either public or private equity form—may be prized by the market longer term, as energy-thirsty emerging markets and new metals-hungry technologies increasingly take center stage.

ANNUALIZED EXCESS RETURNS OVER CASH ACROSS LAST SIX ECONOMIC CYCLES

December 31, 1970 – June 30, 2009 • USD Terms

Sources: FTSE International Limited, Global Financial Data, Inc., National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts, National Bureau of Economic Research, Standard & Poor’s, and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Notes: Data reflect the annualized value of geometrically linked, monthly total returns net of cash across different economic environments. Recessions reflect National Bureau of Economic Research definitions. All expansionary periods were divided into three equal parts by date and named early, middle, and late cycle. If the number of months in each expansionary period was not divisible by 3, an extra month was allocated to early or early and middle. Data end with the end of the last recession in June 2009, given the need to know when the next recession will occur to divide the expansionary period into parts. Asset classes represented by the Global Financial Data (GFD) 10-Year US Treasury Index (US Treasuries), S&P 500 Index (US Equities), a blend of the GFD S&P REIT Index from December 1970 through December 1971 and the FTSE NAREIT All Equity REITs Index from January 1972 onwards (US REITs), S&P GSCI™ Index (Commodity Futures), and a blend of the GFD S&P 500 Energy Index from December 1970 through January 1973 and a custom composite of the Datastream Developed Markets Industrial Metals and Mines Index, Datastream Developed Markets Mining Index, and the Datastream Developed Markets Oil & Gas Index from February 1973 onward (Natural Resource Equities).

Infrastructure

Volatility doesn’t characterize infrastructure investments in the same manner as commodity-related investments. In fact, the former’s low sensitivity to business cycle conditions and market swings are primary selling points. Looking at public real assets performance across the last decade, infrastructure returns were nearly half as volatile as commodity futures, natural resources equities, and US REITs. Even with lower volatility, infrastructure outperformed commodity-linked investments and fared well relative to US REITs during that time period. But many will not consider investing in this seemingly vanilla asset class, even considering the murky economic outlook. We advise otherwise.

The resiliency of infrastructure investments stems from their predictable cash flows, which are often contracted, regulated, and connected to inelastic sources of demand. As private infrastructure equity funds typically finance individual projects rather than corporate entities, they represent a more direct exposure to the underlying assets. Corporate entities may also engage in business lines outside of what is traditionally considered infrastructure, making those cash flows more correlated to conditions in those markets. Assets that are more “pure-play” infrastructure should be more resilient in a downturn and should better diversify traditional business cycle-sensitive investment holdings.

While money has poured into private infrastructure—we estimate funds raised roughly US$55 billion in 2017—and transaction multiples have expanded from roughly 9x EBITDA following the crisis to 12x today, funds have a broad opportunity set within which to invest. Toll roads, utilities, and ports may come to many investors’ minds, but opportunities exist in renewable energy, as well as healthcare (and in debt instruments that support infrastructure assets). These investments offer exposure to some long-term trends that are inaccessible elsewhere. Although tightening global monetary policies may pressure returns, the long-term nature of these investments should provide some comfort to investors fearing the business cycle’s end.

Kevin Rosenbaum, Head of Capital Markets Research

Sovereign Bonds: Hungry Borrowers, But Sated Bondholders?

As 2018 comes to a close, global sovereign bonds appear set to deliver a negative calendar year return, a relatively rare event for this reliable (and sometimes sleepy) asset class. Should the FTSE World Government Bond Index end 2018 in the red (it returned -3.2% in unhedged USD terms year-to-date through November 30), this would be just the third time since the index’s inception in 1985 we have seen negative calendar year returns for both global equities and bonds. Given the implications for other risk assets of the direction of interest rates in 2019 (in short: additional yield increases could be bearish for risky assets, by increasing the discount rate), even those investors with small allocations to sovereign bonds may be interested in the following discussion of the broader impacts of rising debt levels and stingier central banks.

2018 in Brief

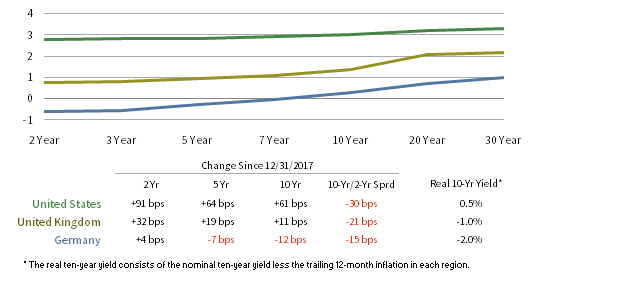

Much of the blame for the year’s negative return for global sovereign bonds can be placed on rising US Treasury yields. The yield on ten-year US Treasuries rose 61 bps over the course of 2018 to 3.0%, and J.P. Morgan’s US government bond index returned -1.4%. The long end of the Treasury curve moved up a bit less than the ten-year note; natural demand from pensions and insurers may be helping to constrain the increase. Moves in other markets were more moderate. Similar maturity UK gilt yields increased 11 bps, and German bund yields fell 12 bps. Nervousness surrounding the election and subsequent budget drama in Italy, and the Brexit negotiations, helped support demand for core Eurozone sovereign bonds. Parsimonious Germany (which runs a budget surplus and where government debt/GDP of 72% is roughly half of Italy’s) has also seen bund prices supported by ECB buying; according to one estimate only about 5% of existing bunds are held by the private sector today.

YIELD CURVES IN THE UNITED STATES, THE UNITED KINGDOM, AND GERMANY

As of November 30, 2018 • Percent (%)

Sources: Bank of England, Federal Reserve, German Federal Statistics Office, Thomson Reuters Datastream, UK Office For National Statistics, and US Department of Labor – Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Note: US and UK inflation data are as of October 31, 2018.

Yield curves have flattened across markets, but to the greatest extent in the United States, where the markets have been factoring in recent Fed rate hikes. Over the course of 2018 the yield on the two-year Treasury increased by 91 bps, narrowing the spread between ten-year yields and two-year yields to just 21 bps. Investors watch yield curves closely, because they have inverted before every US recession since 1960 (however, occasionally the curve inverts without a recession following on its heels). When the Fed will stop hiking is unknown, but for now voting members of the Fed have flagged 3.125% as a reasonable expectation for the Fed funds rate at the end of 2019. 14

Looking Ahead to 2019: What Yield Will Tempt Buyers for the Coming Glut of Treasuries?

At first blush, the disproportionate rise in US yields over the course of 2018 might suggest this market offers value for investors heading into 2019. However, US Treasuries might continue to suffer in 2019 given worsening technicals. Treasury issuance is ballooning to fund the growing fiscal deficit at the same time as the Fed aggressively reduces its balance sheet. Foreign appetite has also been waning, as interest-rate differentials make it painful to own currency-hedged Treasuries.

Debt Supply in Europe Remains Scarce, but US Treasury Issuance Is Spooling Up Quickly

Gilt issuance is tumbling in the United Kingdom, and European QE has hoovered up most of the safest bonds (there are plenty of Italian bonds on offer, and as the ECB stops expanding its bond purchases, availability of other bonds will slowly increase,), but US issuance may continue to run well ahead of buyer interest. The primary culprit is a fiscal deficit estimated at US$1 trillion in the coming year (the result of falling revenues from the corporate tax cut and of a two-year, US$300 billion program of spending increases), though rising interest rates mean debt servicing costs are also soaring. According to Deutsche Bank, the United States will spend over US$600 billion on interest payments in 2019, roughly 50% more than three years ago. Adding it all up, BlackRock believes that in 2019 the government could issue three times the net amount of Treasuries that it issued in 2017.

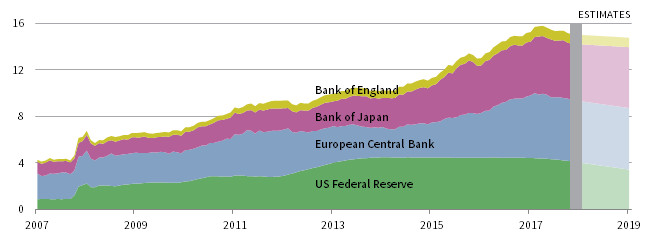

Central Banks: Thanks, But We’re Losing Our Appetite

The assets of four major central banks swelled from US$10 trillion to nearly US$16 trillion from the end of 2013 to early 2018. Since then, stronger economic growth has encouraged a pullback. Since then, central bank balance sheets have shrunk by US$770 billion, and they could dip below US$15 trillion early next year. While still massive, this previous tailwind for bonds (and risk assets in general) is turning into a stiff headwind.

The US Fed has led in efforts to shrink its balance sheet, and is now allowing its balance sheet to shrink by around US$50 billion per month. The ECB, as expected, is following a few steps behind, allowing the interest rate differentials to depress the euro and providing ongoing stimulus to help salve ongoing political wounds. Still, the ECB is expected to make its last net purchases this December, and the bank plans to only reinvest capital beyond that point. That plan, of course, would likely be subject to change if the budget impasse in Europe worsened and if Italian bond prices collapsed (endangering Italian banks). Currently, Italian bonds yield about 300 bps more than German bunds, but Spanish and Portuguese spreads haven’t spiraled higher in sympathy. Meanwhile, the BOJ’s monthly level of asset purchases, while officially unchanged, continues to shrink and is running at roughly US$30 billion per month (about half the official target).

CUMULATIVE BALANCE SHEET ASSETS FOR MAJOR CENTRAL BANKS

December 31, 2007 – December 31, 2019 • USD Trillions • Estimates begin after November 30, 2018

Sources: Bank of England, Bank of Japan, European Central Bank, Federal Reserve, and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Notes: Data are monthly and converted into USD based on the prevailing exchange rate at each month end. The Bank of Japan is estimated to make monthly purchases through 2019 equivalent to the trailing three-month average as of November 30, 2018. All other estimates are based on each bank’s announcements regarding its asset purchase plan through the end of 2019 and converted to USD based on November 30, 2018 exchange rates. Beginning September 2014, the Bank of England discontinued reporting of its total balance sheet asset value, instead detailing approximately 90% of the value of total assets. Therefore, after that time we assume that reported assets total 90% of total asset value (and adjust the reported values upward accordingly).

Hedged European Buyers: Treasuries? You’d Have to Pay Me

Investors might read our bearish preceding sections and posit that the marginal Treasury buyer is pretty clear: with Treasury yields sitting at multiples of the yields on gilts, bunds, or Japanese government bonds, foreign demand should help mop up the large volume of Treasury supply coming in the near future. Unfortunately, this overlooks the impact of hedging costs. Woe betide the bond investor that owns foreign bonds for stability and yet neglects to hedge the currency. What happens to the bond manager in Frankfurt or London or Tokyo who buys a Treasury today? The relatively fat 3.0% Treasury yield, once the currency is hedged, shrinks below their home market’s paltry yields. 15 For more than a year, the yield pickup from a hedged Treasury has been paltry or negative for both UK and German investors, and tilted negative in recent months for a Japanese investor. That’s not to say that non-US buyers will necessarily become heavy sellers of Treasuries (some of their ownership is likely to be sticky), but they cannot be relied upon to pick up much of the increased issuance. Three years ago, foreign investors owned 45% of Treasuries, and today that percentage has shrunk to less than 40%.

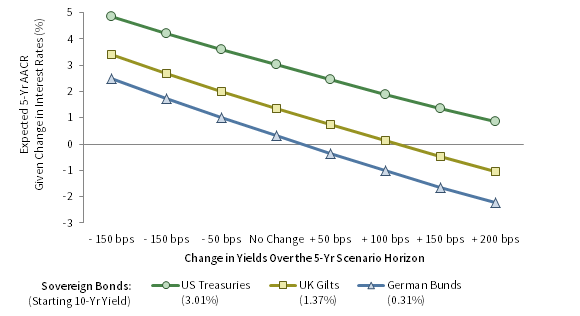

What Do Today’s Yields Mean for Returns?

Investors might wonder whether today’s starting yields would offer sufficient cushion to offset any price declines, should yields need to rise to attract buyers. Even if yields only rose by 50 bps, bunds today would fail to generate a positive return over the next five years. 16 Gilt returns would likely be positive in the face of a 100 bp yield increase, but would dip into negative territory if yields were to move to levels similar to those offered today by Treasuries. Given a starting yield of 3.0%, a ten-year Treasury’s return would be much more insulated from yield increases, remaining positive even assuming a 200 bp increase in yields. Treasury yields have doubled compared to the level at their nadir in July 2016, boosting the attractiveness of their prospective return. We refer here to nominal returns; real returns would likely be materially worse. Recall from this section’s first chart that the real yield for bunds and gilts is today hovering around -2% and -1%, respectively (it’s positive in the United States: 1%).

EXPECTED NOMINAL 5-YEAR AACR FOR 10-YEAR SOVEREIGN BONDS UNDER VARIOUS INTEREST RATE SCENARIOS

As of November 30, 2018

Sources: Bank of England, Federal Reserve, and Thomson Reuters Datastream.

Notes: Projections are based on the starting 10-year yield for each region. Shifts in yield are based on a starting yield that subsequently approaches terminal yield on a linear basis over a period of five years. The scenario does not incorporate a roll-yield assumption or an allowance for default losses.

Investors that fear that yields are headed much higher could boycott the longer end of the curve. With yield curves relatively flat, the yield pickup from owning the more yield-sensitive longer bonds is not all that large. A two-year Treasury, for instance, has about one-quarter as much interest rate sensitivity as a ten-year Treasury, but offers about nine-tenths as much yield. Of course, investors shortening their duration are reminded that an inverted yield curve (not today’s relatively flat curve) is associated with near-term slowing of the economy, an outcome historically has rewarded holders of long-term bonds.

Summary

The bond market has not delivered for investors in 2018. And 2019 is not looking great either, given that central banks and other recent categories of buyers are unlikely to mop up the increased supply that stems from rising US fiscal deficits. That said, 2018’s yield increase makes bonds less unattractive (especially in the United States), and yields of Treasuries and gilts would need to move much higher for investors to receive negative five-year returns. Investors that are focused on the risk of higher yields (and comfortable underperforming in any periods when bonds are surging and the rest of the portfolio is likely suffering) might consider shifting some exposure to the front end of the curve, accepting a slightly lower yield for a much smaller sensitivity to interest rate changes.

Sean McLaughlin, Head of the US Southeast & Mid-Atlantic Endowment & Foundation Practice

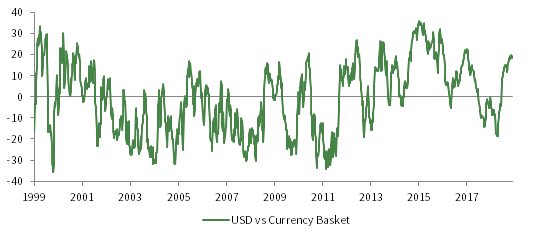

Currencies: Breakout, or Breakdown?

2019 will see whether the US dollar can continue to rally and breakout to reach new highs for this cycle, or lose steam and breakdown, confirming that the USD bull market is over. While we think the USD bull market has more to run, we would not be surprised to see the US dollar suffer another sharp reversal in 2019, especially if the Fed fails to follow through on hiking interest rates.

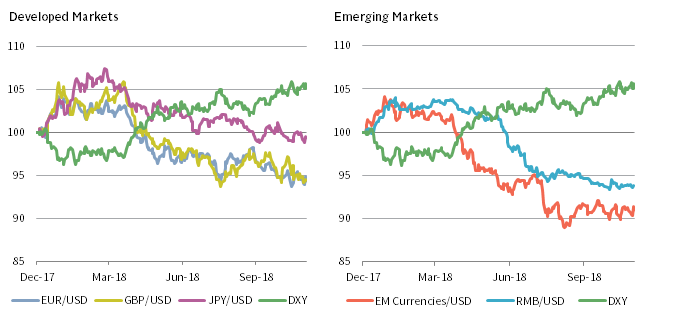

2018 in Brief

2018 was the mirror image of 2017; the US dollar began the year by weakening sharply, only to reverse course and enjoy a broad-based rally for the rest of the year. The turning point was April 2018, when hawkish comments by new Fed Chairman Jerome Powell combined with strong US economic data and disappointing data from Europe powered the dollar higher. At the same time, the Trump administration’s aggressive trade policies and rising US interest rates put emerging markets currencies under pressure. Emerging markets countries with current account deficits were hardest hit, with Argentina and Turkey undergoing a classic currency crisis. China was also hit, with the renminbi tumbling 6.2% to a decade low and nearly breaching the USD/CNY 7.0 level. All in all, by the end of November the DXY basket that tracks the US dollar versus major developed markets currencies was up 5.6% for the year, and a basket tracking emerging markets currencies was down 9.1% relative to the US dollar.

YTD 2018 CURRENCY MOVEMENTS

As of November 30, 2018 • December 31, 2017 = 100

Notes: Data are daily. EM Currencies is based on the implied basket of currencies in the J.P. Morgan GBI-EM Diversified Index.

Looking Ahead to 2019

2019 could see a repeat of 2017’s sell-off in the US dollar. After such a strong run, the market is already net-long the dollar to almost the same extent as 2017. Continued USD strength is predicated on the Fed continuing to signal it will hike rates 75 bps in 2019 and 25 bps in 2020. Any sign of wavering in this regard could catalyze a sharp reversal in the US dollar. Investors had a taste of this in late November when the US dollar sold off abruptly following comments by Fed Chairman Powell that the Fed Funds rate is “just below” the neutral level. While market pundits debate the true meaning of Powell’s comments, a dovish Fed would clip the wings of the US dollar. This is especially the case should the ECB or other global central banks turn more hawkish and begin hiking rates. At the same time, rising US rates have increased negative carry for non-USD investors hedging their currency exposure, and this may crimp demand for US assets in 2019.

Sources: Thomson Reuters, Thomson Reuters Datastream, and US Commodity Futures Trading Commission.

Notes: Data are weekly. USD positioning tracks the net aggregate futures positions of non-commercial speculators against the Australian dollar, Canadian dollar, euro, Japanese yen, Mexican peso, New Zealand dollar, Swiss franc, and UK pound traded on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange as a percent of the total open interest. A negative number indicates a net short position on the dollar, while a positive number indicates a net long position.

A bout of USD weakness would see emerging markets currencies rally sharply, as weakness in emerging markets currencies in 2018 has driven valuations to the edge of our undervaluation range. Rate hikes by EM central banks could provide some support for EM currencies in 2019. However, EM currencies still face the headwind of tightening global liquidity. Indeed, as the Fed continues to contract its balance sheet, the ECB ends its QE program, and the BOJ continues to slow its asset purchases, global liquidity may contract in 2019 for the first time in nearly a decade. Add to this the prospect of continued US-China trade tensions, and we remain cautious on EM currencies, although we admit they may be primed for another short-lived rebound. Indeed, the recent “cease-fire” in the US-China trade war agreed to at the G20 Summit in Argentina triggered such a bounce, although there remains broad skepticism that the peace will last beyond the 90 days given to strike a formal trade deal.

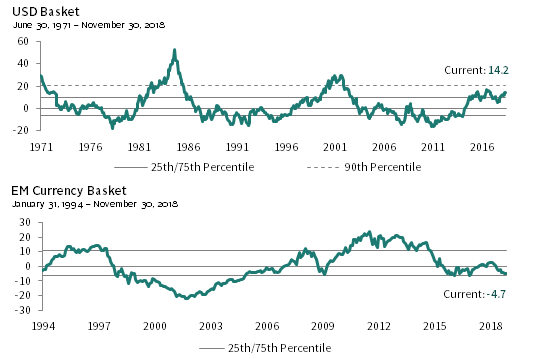

REAL EXCHANGE RATE: PERCENT FROM MEDIAN

Percent (%)

Sources: International Monetary Fund, MSCI Inc., and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Note: The USD basket includes six developed markets currencies and the EM FX basket includes 20 emerging markets currencies.

Summary

The US dollar may come under pressure in 2019, given that market positioning is almost as stretched as in early 2017. The likely catalyst for any renewed dollar selling would be any signal the Fed might not follow through with rate hikes in 2019, or signs other central banks are turning more hawkish. However, political risk in Europe (both Italy and Brexit) and ongoing US-China trade tensions also complicate the outlook. Our big picture outlook for currency markets has not changed; we are near the end of the strong-dollar cycle, and both history and valuations suggest the US dollar will weaken over the coming years. Increased US fiscal deficits also add to the negative longer-term outlook for the US dollar. 17 However, this may not occur until after the next US recession, as the USD typically rallies around recessions amid the global flight to safety. Thus, the US dollar may remain well supported until the next recession, the timing of which is uncertain.

Aaron Costello, Managing Director

Conclusion

As we head into 2019, a key question for investors is if the economic expansion is coming to a close or if the economy is downshifting to a slower rate of growth. We see prospects for continued economic and earnings growth: fundamentals remain solid in most places and typical recession indicators are not yet flashing red. However, the US economy is in the later stages of its cycle, growth is slowing globally, rates have been trending up—recent softening aside—and market volatility has been on the rise. As economic growth remains above trend, we continue to see nascent inflation pressures in the United States that suggest the US Fed will continue to tighten and shrink its balance sheet, creating rate volatility as Treasury supply outruns structural demand. Relative US economic strength and related higher US interest rates have supported the US dollar, creating pressures for markets dependent on USD liquidity, particularly emerging markets, at a time when Chinese economic growth is decelerating. The outlook is further complicated by ongoing geopolitical risks.

Because these risks and uncertainties are offset by continued conditions for growth, we recommend investors remain roughly neutral on risk assets, while also developing a strategy for managing through a recession-related bear market. Our central view is that the economic expansion will continue through 2019, but that volatility will remain elevated (i.e., trending closer to historical averages than to the very low levels of the recent past) in the absence of aggressive monetary stimulus. In other words, as in 2018, investors may see more risk and less return than in recent years. Even though the market may yet reach new highs over the coming year, it is never too early to develop a plan for navigating the next broad-based bear market. It is always difficult to stick with a plan while in the grip of market stress, and to do so without prior review and debate among stakeholders would be nearly impossible. Indeed, given the length of this bull market, it is quite likely that investment committee turnover has left many investors with stakeholders that have not been through a bear market together or had a serious discussion about strategy in such an environment.

What should such a strategy look like? Investors should first seek to understand their risk tolerance and then seek to maintain relatively neutral risk positions. Second, identifying liquidity uses and sources, especially in stressed environments, is essential to navigating through difficult periods while meeting spending obligations and capital calls. After those important issues are taken care of, investors should then look to maintain a high level of diversification across investments, seeking out exposure to assets that can be expected to provide competitive long-term returns from exposure to a range of economic drivers.

Among the most defensive assets, we recommend holding some cash or short-duration high-quality sovereign bonds in place of their longer-duration counterparts, particularly where yield curves are flat, as well as certain investment strategies that have relatively low reliance on economic growth, such as trend-following strategies, hedge funds that have low sensitivities to equity markets or credit spreads, private investments in infrastructure assets with relatively predictable cash flows, and other diversifying illiquid strategies including royalties and life settlements. In implementing the illiquid strategies on this list, investors should first evaluate if they have the ability to take on more portfolio illiquidity, even as these strategies distribute income. Second, investors should weigh the diversification benefits of such investments against other illiquid investments with higher return prospects when well-implemented, such as venture capital and private equity (especially early-stage venture, lower/middle market growth equity, and sector-focused funds, as well as co-investments and direct investments in secondaries). We think most investors have room for both types of illiquid assets in portfolios and regard diversification as valuable.

With regard to cash, it can be used in combination with higher risk/reward investments to create a portfolio risk barbell by substituting for a portion of sovereign bond allocations and liquid inflation-sensitive assets, such as commodities, intended to support spending when equities hit a rough patch. Since cash can serve as an effective liquidity reserve under a variety of economic scenarios, covering a year or so of anticipated spending demands a smaller allocation to cash than to a combination of sovereign bonds and inflation sensitive assets. This in turn allows investors to allocate more of the portfolio to investments with high expected returns, providing a more certain spending reserve for stressed environments, while leaving the portfolio’s risk/reward profile unaltered.