Implementing a Sustainable and Impact Investing Strategy – A Family Perspective

In the second of our two-part series on philanthropy and sustainable investing, we take a closer look at portfolio implementation best practices for families. In doing so, we outline how families may wish to identify opportunities within sustainable and impact investing (SII) themes. We discuss the broad opportunity set, how to construct and then actively manage an investment portfolio of these strategies, and why families are well positioned to deploy capital in this space.

Implementing an SII strategy is complex because it does not occur in a vacuum; rather, it is one important element in a larger portfolio construction process. For the purpose of this piece, however, we focus on the nuances involved in implementing an effective SII portfolio strategy. We put forward four guiding principles and conclude that a ‘one size fits all’ approach doesn’t work – individual choices should be made based on family values, goals, and circumstances, including available time and resources.

Opportunity Set

The Global Sustainable Investment Alliance currently estimates that total SII assets stand at USD 35.3 trillion globally (35.9% of total global AUM), an amount that has grown substantially in recent years. This is seemingly good news, as there are now numerous opportunities for families to consider. (Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, ‘Global Sustainable Investment Review 2020,’ Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, July 2021. This combines environmental, social, and governance (ESG) and all impact-related investment opportunities.) However, on a more practical level, this can be slightly overwhelming for families trying to identify relevant, aligned, and compelling investments within such a large universe. A useful tip is to focus on how to invest – in other words, what to exclude as well as what to include. This can help avoid technical debate over terminology and better enable the portfolio construction to align with the family’s vision (Figure 1).

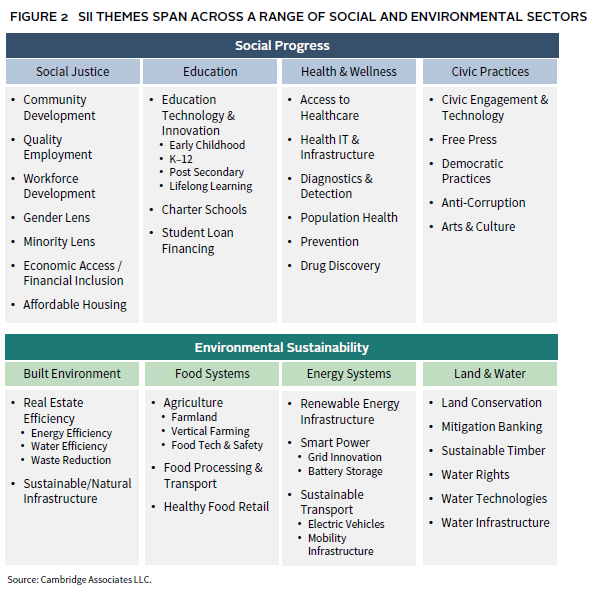

Screening for what not to invest in is an easy way to reduce the investment universe and is best practically done by agreeing to a list of sectors that the family does not want to have exposure to. Once in place, a debate can then be had about what to include. Here again, a framework is useful to guide conversations. Figure 2 presents an example of sectoral lenses that families can consider.

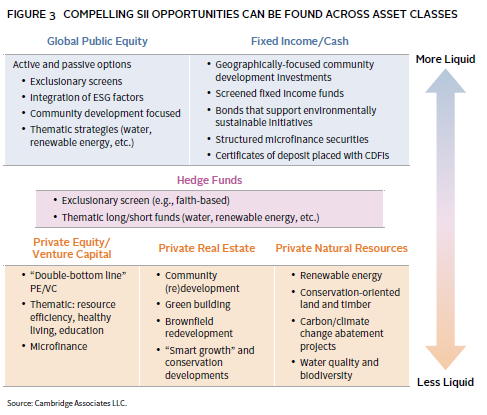

Equally, opportunities can also be subdivided by liquidity profile (Figure 3) so as to create a thematic/liquidity matrix that reflects a family’s values, as well as the opportunity set.

The Role of SII – Re-wiring Risk and Return

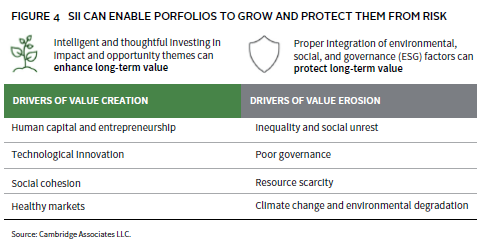

With a large proportion of global assets influenced by SII themes, it is rational to argue that SII is financially material to all investors, either directly or indirectly. What is perhaps less apparent is that SII can be both a risk mitigator as well as a return driver within a portfolio, as shown in Figure 4.

Intuitively, it makes sense that over the long run, well-governed – as well as socially and environmentally progressive – companies are likely to be more stable and efficient businesses, all other things being equal. However, the traditional approach of evaluating investments by looking to identify short-term drivers of risk and return can result in an excessive focus on quarterly earnings, with less attention paid to strategy, fundamentals, and long-term value creation. Many companies respond to short-term pressures by reducing expenditures on research and development and foregoing investment opportunities with a positive long-term potential. As a result, these companies can be discouraged from developing sustainable products, investing in measures that deliver operational efficiencies, developing their human capital, or effectively managing the social and environmental risks to their business. If families are able to view SII initiatives through a longer-term, risk mitigation lens – which is often possible when thinking about multigenerational wealth – they put themselves at a structural advantage over other investors. In so doing they also direct capital to businesses that are operating more sustainably, thereby incentivising management to continue to think progressively and with an eye to the long term.

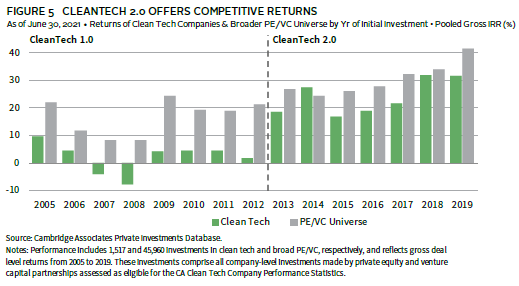

A common misconception is that SII, and impact investing in particular, comes with a trade-off between impact (social and environmental return) and risk-adjusted financial return. Whilst recognising that in all asset classes there will be a dispersion of returns, the financial competitiveness of SII strategies is now backed by clear evidence. Clean technology is a case in point. As can be seen in Figure 5, from 2005 to 2012 – a period referred to as ‘Cleantech 1.0’ – returns from clean technology were not compelling, as the commercial viability of many of the technologies were contingent on governmental subsidies. That changed after 2012 (‘Cleantech 2.0’), when second-generation breakthroughs enabled technology to be viable and therefore scalable on a stand-alone basis. The clean technology sector outperformed almost all others in the subsequent decade and its returns competed with private equity and venture, which have historically been some of the best-performing asset classes of all.

SII investments, then, have a dual function in a portfolio – to generate returns and reduce risk.

SII Portfolio Construction Decision Making for Families

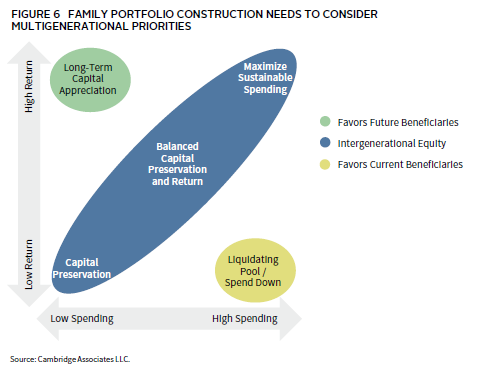

A number of factors should be considered in constructing a robust SII investment portfolio. Some of these are qualitative, such as articulating individual values and priorities, while others are more quantitative and include, for example, risk, return, and liquidity expectations. Ensuring that each element is considered is an important top-down starting point as this will shape the look and feel of the portfolio, as well as how it performs over time. However, this is easier said than done when constructing one family portfolio with multiple beneficiaries, as complexities can arise due to differing family member priorities. Income requirements are a case in point as future generations who have no current-day income requirements would make an argument for higher returning, lower income-generating investments. Conversely, members who are current beneficiaries are likely to favour lower risk, more liquid, and higher income-generating investments as they age (Figure 6).

One way around these competing interests is for family members to agree on and document their investment philosophy in an ‘investment charter’ prior to drafting a formal Investment Policy Statement. This concept is similar to charters designed to mitigate behaviourial risks within families; however an investment charter focuses on the compromises each family member is willing to accept to stay true to the family’s guiding (SII) principles. If this is not possible, and the pool of wealth is sufficient, it may make sense to create individual portfolios for members, each of which can be completely tailored to specific interests. Ultimately, the best solution will be what the family is most comfortable with.

With this in mind, below we outline four guiding principles that can help the SII portfolio construction exercise:

1. Pick Your Pillar

As we have discussed, the opportunity set within SII is broad but a good starting point is to pick a pillar, or pillars, that the family or individual really cares about, and focus the investment strategy in these areas (across asset classes). This can serve to improve focus and achieve more impact as a result.

2. Best in Class is Not Always Best

When pursuing SII many families tend to assume that, to have the biggest impact, they should direct their attention to the most highly rated, well-managed businesses. This makes intuitive sense, but actually may not be the best strategy, for several reasons. Firstly, purely from a financial perspective, if the market recognizes the same as you, then these businesses are likely to be in demand and therefore expensive. Expensive companies can still be profitable investments but, all other things being equal, buying good companies cheaply is likely to be a more attractive proposition.

Secondly, if families wish to be truly impactful, there is a strong argument for directing capital to well-run, second-tier businesses, or to businesses transforming their strategy. Examples could include high-carbon industries such as cement/steel/auto manufacturing moving to greener materials (e.g., green steel), as well as oil exploration companies transitioning to producing energy from renewable resources. We caveat this by recognising that family entities operating on a stand-alone basis are unlikely to have the power to influence decision making in large, listed businesses. However, by collaborating with like-minded investors, or via advisors who can engage on behalf of all of their clients, family capital can be catalytic.

Thirdly, by definition, in simply focusing on the very best companies, families are significantly reducing their investable universe, which increases tracking error versus a benchmark and also likely increases the volatility of returns (due to a higher position concentration). Whilst not a problem in itself, investors should be aware of, and willing to accept, these risks.

3. Alignment and Measurement

A third tip is to assess whether company management is actually aligned to the investor’s values and whether the company has established specific criteria by which to measure SII success or failure. Measurement is particularly important as, with the growth of SII, many businesses have sought to attract capital by marketing their green credentials without tangibly evidencing progress made (commonly referred to as ‘greenwashing’). To avoid this, careful due diligence and ongoing inspection is essential to ensuring that chosen companies or funds produce specific, measurable, short and long-term targets, which can be reported on at least annually. In so doing, management should be renumerated not just on the financial performance of the company, but also specifically (and separately) on SII criteria.

4. Consider Illiquid Investments

Families also should recognize that being truly impactful takes time. Consequently, ensuring that investment funds or individual companies have time to fulfill their potential often requires accepting some illiquidity. This is not to say that investors can’t find socially or environmentally impactful businesses that are listed on exchanges, and so may be sold at the click of a button, but to solve the world’s hardest problems – at a micro or macro level – often requires patience. As a result many impact funds tend to be structured as private vehicles, which typically have ten-year lock ups. Recognising that great returns and long-term positive impacts don’t materialise instantly is an important starting point for families and is a good reminder that conducting thorough due diligence on SII investments prior to committing to them is extremely important.

Conclusion

Much has been written on SII in recent years, but in this paper we have tried to keep family investors front and center. In so doing, our core message is that each family portfolio will have unique goals, but also often specific constraints. A generic approach to implementing sustainability is therefore not recommended. Instead, we suggest focusing on family values and priorities whilst remembering that investors don’t need all the answers on day one – SII is a journey. The most important thing to do is to start the iterative process of learning by doing. A clear focus, combined with an open mind, can help drive continued success.

The other paper in this two-part series, Unblurring the Boundary Between Philanthropy and Impact Investing for Families, addresses some of the motivations behind philanthropy and how philanthropy relates to impact investing.