The Foundation of Good Governance for Endowments and Investment Committees

Suboptimal governance can extend disappointing performance or perpetuate suboptimal past decisions. By contrast, good governance leads of its own design to necessary mid-course corrections. To create the conditions for good governance, endowments should assess whether they have in place the appropriate model for portfolio oversight and management, are upholding their fiduciary responsibilities, and are learning about peer best practices in structure, process, policies, and role of the portfolio.

Concern about governance is in the air. In conversations with our clients it comes up all the time, in three specific ways:

- Worry about whether the long-term investment portfolio is being managed optimally

- Unease about fiduciary responsibilities

- Curiosity about “best practices” in place at other institutions or organizations

Some have concerns that insufficient steps were taken to make governance more robust after the wake-up call of the 2008 financial crisis. Others worry about investment return assumptions or distribution (spending) rules, and how to deal with such misgivings—e.g., decisions much discussed but not taken, divided committee, inattentive committee, “analysis paralysis,” or any of many other ailments. Still others are discomfited by occasional (not necessarily accurate) headlines describing institutions’ investment mistakes or fiduciary shortcomings. On the bright side, some portfolios have grown so successfully—through performance, fundraising, or both—that trustees wonder whether a different governance and/or management are in order for the larger assets.

Investment return prospects in a low-return environment, regulatory pressures, the public focus on “large endowments” and tax-favored treatment, and (for some) the rapid portfolio growth through capital campaigns have combined to put governance at center stage. All eyes are on board decisions. A regrettable investment performance vis-à-vis peers, a worry about purported conflict of interest, an overlooked debt covenant, a fraught budget process involving liquidity or endowment spending, an internal disagreement about the right portfolio return assumption, an upcoming capital campaign—governance determines if and how such matters can arise, and whether they will be handled well or poorly.

The three types of governance issues listed above are related and yet distinct, raising different questions:

- Optimal portfolio oversight and management: governance responsibilities vs management responsibilities. Is our long-term investment portfolio (LTIP) being dealt with adequately? Who’s supposed to be doing what? (What are the roles of the investment committee members, the investment staff, and external advisors?) Does this change when our portfolio reaches a certain size? How many people do we need to look after our portfolio? What are their roles, and how much will it cost?

- Fiduciary responsibilities. What are our legal obligations? Are our overarching legal guidelines (charters, and/or bylaws) being followed? Have recent changes in the law 1 been incorporated into our decision-making? Do we have the appropriate policies in place for investing, spending (distributions), conflicts of interest, and gift acceptance?

- Best practices. What are the practices that work well? How are our best-performing peers handling their governance? Would it be relatively easy, or difficult, to adopt changes to improve our investment decision-making?

These three ways to address governance can blend into one another. Nevertheless, it’s useful to address them separately, if only to reduce the complexity of the discussion and to improve the articulation of next steps.

Endowment or LTIP Management

Many “governance” discussions are actually discussions about who should handle the management of the endowment or LTIP. No investment committee can shed its fiduciary responsibility: governance cannot be delegated. But management can certainly be delegated, and it should be, once assets become large enough to challenge the abilities, experience, and time commitment of investment committee members to deal with alone. After recognizing the advisability of delegating management, then the next question is: should the management be internal (an internal chief investment officer) or external (an outsourced chief investment officer or OCIO)? 2

How large is “large enough”? No demarcation applies to all. If the investment committee consists of individuals with enough time, enough skill, and an excellent portfolio track record—and the ability to continue to provide outstanding implementation—then perhaps they can manage successfully as assets grow. However, most committee members experienced in institutional investing have other professional responsibilities to meet (their “day jobs”), or they may live too far from the institution to show up in person at the meetings necessary to successful implementation. Some may worry that their knowledge about certain complex asset classes is insufficient, or they may simply prefer not to be held accountable for delivering at this level of granularity. Finally, in addition to delivering on implementation, they are also responsible for the “big picture.” Needing to deliver on both governance and management is not an attractive option for most investment committee members. And indeed as assets grow, it becomes ever more difficult for a committee without adequate staff to meet the fiduciary standard of care across the portfolio.

Thus, sooner or later, investment committees come to the staffing issue. How many people does it take to run an LTIP with sufficient skill? Can we attract a top-notch CIO to our location? How much will we have to pay the CIO, and the additional staff picked to provide further expertise? How much will it cost to retain them should they become successful and thereby receive other job offers?

And if we consider an OCIO, how much discretion are we willing to give? How much customization can the OCIO provide us? Will we own the assets in our portfolio, or will we own unitized shares of a commingled portfolio? How much breadth will we be given, in terms of investment opportunities? Will we be limited mostly to the OCIO’s in-house products or will we have access to the full universe of possibilities? If we decide to fire the OCIO, or to exit partially, can we do so without a delay, and would we keep our positions (our assets) or be required to receive cash for the value of our positions?

What is an appropriate amount to pay for endowment management, whether internal or external? If internal, do we want a separate office or “management company”? Do we want the CIO to report to the president of the institution or to the top financial person with responsibility for the institution’s entire business model? If external, should we outsource all portfolio management, or only certain parts of the endowment or portfolio? Should we book the management fees directly to the endowment, in accordance with most accounting guidance, or charge the fees to the annual operating budget?

To answer these important questions, a governance study may well be in order, especially for institutions that have had undesirable turnover in investment staff, have seen their LTIP grow substantially through both performance and gifts, or have investment committee members uneasy about responsibilities that entail management as well as governance. Governance that makes arrangements for excellent management, as well as strong oversight, is a goal central to the financial health of any endowed institution.

Fiduciary Responsibilities

Necessary to strong governance is also the successful fulfillment of fiduciary responsibilities, as defined by state and sometimes federal law. A well-designed management/governance structure, as just discussed, will readily accommodate the fulfillment of fiduciary responsibilities. A suboptimal arrangement will make this more difficult.

The standard fiduciary responsibilities of board members of tax-exempt institutions are the duty of care, the duty of loyalty, and the duty of mission (or “obedience”). Duty of care requires the most time and focus on the part of a board member. The trustee must not only be present (preferably in person) 3 at virtually all committee meetings, but must also exercise sufficient “care” to identify the relevant issues, to become knowledgeable about the issues, and to have weighed the choices systematically and with sufficient due diligence before making decisions. A corollary is that board members must have access to sufficient investment resources—whether internal or external—to make informed decisions.

The duty of loyalty is typically met by means of a conflict of interest policy that spells out a process for dealing with any conflicting loyalties. The policy must be adhered to and periodically reviewed, because over time additional kinds of conflicts of interest may arise. Rarely can all conflicts be avoided, but they can be managed, through policy.

The duty of mission means making decisions that are consistent with the mission of the institution as a whole. Breach of this duty is less frequent than missteps in connection with the other two duties. (In some states, mission is defined as “obedience,” as in obedience to the law.)

The overlap between the particular portfolio oversight/management arrangement on the one hand and fiduciary responsibility on the other hand usually involves the investment committee’s adherence to the duty of care. Specifically, is the portfolio run in such a way that investment committee members can adequately fulfill their duty of care? And if not, how can it be better run? The duty of care is most often the focus when endowment decisions go awry. In addition, though less frequently, the absence of a conflict of interest policy, or a failure to enforce such a policy, can result in a breach of the duty of loyalty. A poor decision that is or even appears to have been influenced by unexamined divided loyalties will put an investment committee in an uncomfortable position.

Best Practices

Here we get into the specifics of what works, and what does not, when it comes to the day-to-day business of portfolio oversight and management. Boards and investment committees that adopt a combination of best practices generally see better portfolio performance. Having reviewed their situation in terms of best practice (or lack thereof), some committees may find it daunting to move from where they are to where they would like to be. They can learn from other committees’ experience in correcting subpar attributes.

The important areas of best practice are: the structure of the investment committee, the process (how it does its job), the governing policies, and how the portfolio serves the broader institution or organization.

When it comes to structure, there are many, many levers for effecting change or preserving excellence, as the case may be. No committee lives forever in its present form, and ensuring both continuity and new perspectives (e.g., via effective terms of service) is important, particularly in situations where assets have grown substantially and/or the investment environment has changed, whether suddenly or gradually.

Process is as important as structure. The best driver behind the wheel cannot go anywhere without established roads. As with the oversight/management arrangement (whether internal or outsourced), process bears most upon duty of care. Without a well-functioning process, diligence and perspective can fall short. Investment oversight can become bogged down in less essential disagreements or unfocused discussions, or it can stall in a dead end that leads to no decisions. Important issues can be tabled indefinitely, or “fall off the agenda,” or become buried by temporary crises. There are many ways to go wrong, but certain steps can reduce the probability of adverse outcomes.

Governance-related policies require considerable judgment in language and some thought with respect to breadth of coverage (how much should be captured and spelled out in writing?). Best practice as it relates to investment committees generally involves the following policies: investment policy, distribution policy (“spending policy”), and conflict of interest policy. Other policies may be in place, as required—for example, a withdrawal policy in place at some “internal banks.”

Finally, the portfolio’s relation to the institution and its enterprise risk must not be overlooked. Too often, investment committees focus only on performance and intra-portfolio risk, with little regard for how the performance relates to the broader institution. Thus, for example, a higher-growth investment portfolio may carry a level of volatility that is unexpected and unaddressed by spending (distribution) policy. Or, alternatively, the risk may be failing to earn what’s expected to support the institution—for example, an overly conservative liquidity profile. Best practice requires process and policy adjustments to address enterprise risk.

Best practice overlaps with fiduciary responsibility in all three areas: duty of care (especially process), duty of loyalty (conflict of interest policy), and duty of mission (adequate attention to the portfolio’s support of the enterprise and its mission). It overlaps with portfolio oversight and management primarily in the area of best practice structure; e.g., size and composition of the investment committee in both internal and outsourced portfolio management.

Summary

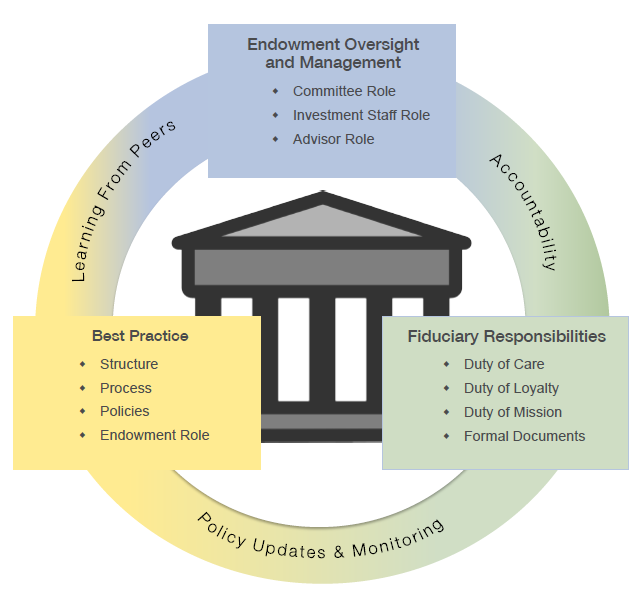

On the following page we depict the foundation of good governance. The three areas discussed above are shown in the boxes, and the areas of overlap are shown between the boxes. Together these essential pieces provide a strong foundation for investment oversight.

Governance can be a headache, or it can work so well that an institution is barely aware of it as the necessary decisions are made and implemented. We’ve worked with organizations that have questions or difficulties with all three kinds of governance issues, or with only one. Improving governance can be accomplished in a variety of ways and no two ways are exactly alike, because no two institutions are exactly alike. A given problem has multiple possible solutions, and few need be difficult. Observable outcomes are not necessarily predictable: good investment performance can coexist with poor governance, yet successful performance cannot be sustained into the future when there are governance headwinds. Conversely, poor performance can accompany good governance, yet with good governance in place, such performance improves in the future as better governance drives the process to produce the necessary portfolio adjustments.

And yet, governance is not carved in stone. Even an institution with a firm foundation in place cannot assume that its good governance will continue indefinitely without occasional review. The investment environment may change, requiring new skill sets on the investment committee. New conflicts of interest may arise through external events. Committees may fall into suboptimal process patterns. The key policies may need to be updated. And so forth. For these and other reasons, institutions are well advised to undertake a routine periodic governance review or update, perhaps every five or ten years, or as circumstances require.

In conclusion, suboptimal governance can extend disappointing performance or perpetuate suboptimal past decisions. By contrast, good governance leads of its own design to necessary mid-course corrections. Given that no individual and no committee is always right in its investment choices, it is far preferable to identify the necessary portfolio adjustments and deal with them not as a matter of stress, but as a matter of routine that arises from a firm foundation for good governance.

The Foundation of Good Governance

Footnotes

- For example, the Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act (UPMIFA), in most states; the federal law governing private foundations, where appropriate; and nonprofit corporate law, trust law, and case law where appropriate.

- Endowment/LTIP tasks are: determining investment strategy, setting policies, and evaluating performance. Endowment management tasks are: implementing policy, selecting and terminating asset managers, rebalancing the portfolio, and monitoring portfolio performance. External expertise can be engaged at the governance level, the management level, or both.

- Best practice, if not bylaws, require a sufficient level of in-person attendance.

About Cambridge Associates

Cambridge Associates is a global investment firm with 50+ years of institutional investing experience. The firm aims to help pension plans, endowments & foundations, healthcare systems, and private clients achieve their investment goals and maximize their impact on the world. Cambridge Associates delivers a range of services, including outsourced CIO, non-discretionary portfolio management, staff extension and alternative asset class mandates. Contact us today.