Don't Discount Fixed Income Investing for US Pension Plans

Most plan sponsors recognize the importance of including long-duration fixed income in their pension portfolios. Doing so is essential to pension plan de-risking, as it can protect funded status by hedging interest rates and reducing equity beta risk. While this approach appears simple enough, a great deal of nuance lies beneath, especially for credit-oriented strategies. Although long-duration credit may provide a sound hedge and yield match for pension plan liabilities, an array of mismatches still exist that can expose a plan to funded status deterioration. The general notion is that active management in fixed income helps avoid this “slippage” in portfolios. Yet effective active management can actually contribute much more by also serving as a valuable source of manager value-add, or alpha. 1

While alpha is commonly recognized as a key lever in maintaining or improving funded status, it is often mistakenly limited to purely equity or lower-liquidity investment opportunities. For plan sponsors, this can be a costly misconception and result in leaving a powerful investment tool unused. In fact, Cambridge Associates’ research shows that active fixed income management can contribute valuable alpha, resulting in significant benefits to plan outcomes. Ignoring the potential advantages of this approach can result in undue funded status risk for hibernating 2 plans, or add additional years to a pension plan’s expected lifetime for organizations wishing to terminate their plans.

Gauging (and Addressing) Pension Plan Liabilities

To calculate the market value of liabilities for pension plans, US and international accounting standards require the use of a discount curve derived from corporate AA bond yields. Pension plan liabilities are long-term in nature. As such, they are sensitive to interest rate movement risk, or changes in the US Treasury rates and credit spreads that comprise AA bond yields. This risk ultimately manifests itself in funded status and contribution 3 volatility. To help compensate for these risks, plan sponsors use long-duration fixed income—mainly US Treasuries and investment-grade credit—which have similar risk profiles to the liability.

Although long-duration credit can provide a good hedge for pension plan liabilities, two significant basis risks still exist:

- Pension plan liabilities are valued under AA-rated bond yields, while most long-credit managers use the entire investment-grade universe (BBB – AAA yields). These fixed income asset classes inhabit different ranges of yield movement over time and can therefore deliver a wider range of potential returns. As a result, fixed income portfolios can behave differently than liabilities.

- Pension plan liabilities are immune from credit downgrade or default risk, but the same is not true for the investable fixed income universe. Increased funding status risk may result, as asset portfolios may experience losses from these events, while liabilities will not.

Uncovering Alpha to Help Manage Risk

There is no good answer to compensate for these pension portfolio risks, outside of earning enough in the investment portfolio to overcome any funded status deterioration from any basis mismatch. This outperformance can come from the overall asset allocation, or within individual allocations through manager alpha.

A pension plan’s funded status, or a comparison of assets to liabilities, is a central focus of plan sponsors. Dispersion of plans’ funded status in the United States is extremely wide, ranging from poorly funded (i.e., below 70% or more) to overfunded (i.e., more than 100%). Typically, a fixed income allocation changes along with a plan’s funded status, with better funded plans employing more fixed income in the portfolios. The allocation is set up by a glide path, which is a systematic way of de-risking a pension portfolio, reallocating over time from growth-oriented strategies (e.g., equities) to liability-hedging strategies (e.g., investment-grade fixed income).

For underfunded plans with lower allocations to fixed income, alpha generation in the fixed income portfolio may have a lesser impact. Here, the growth portfolio dominates the allocation and may include larger allocations to certain asset classes, such as private equity and venture capital, that have much higher alpha-generating potential. Fixed income for these allocations is likely tilted more toward Treasury securities to compensate for significant beta exposure from the rest of the portfolio—resulting in less fixed income alpha potential.

For better funded plans with higher allocations to fixed income, the growth portfolio may not be able to achieve both funded status improvement and alpha generation without taking undue funded status risk. At this stage, private equity and venture capital strategies can be less appropriate. The growth portfolio is better suited to more liquid and efficient asset classes with lower alpha expectations. Fixed income for such plans is typically geared toward significant reduction in funded status volatility to preserve that status, which can mean that alpha generation is put aside as a top objective. The result is often the mistaken perception that fixed income is meant only for risk reduction—with many plan sponsors denying themselves an opportunity for valuable degrees of return generation and funded status improvement.

In fact, pension plans could potentially generate 30 basis points (bps) to 180 bps of additional return from their fixed income managers over a market cycle, which can translate to between 1.5% and 5.6% of additional funded status improvement over a five-year period. 4 This outperformance can amount to millions of dollars, and can make or break the decision of whether the plan can effectively terminate or hibernate.

How Active Can Beat Passive in Fixed Income Investing

Most investors are aware of the decades-old debate about active versus passive investing. The passive camp contends that over the long term it is impossible to outperform the benchmark, while the active camp suggests that market inefficiencies can provide for manager value add. When it comes to equity investments, a definitive answer to this debate is likely to remain elusive. But for plan sponsors considering fixed income strategies, more clarity is available. Because fixed income markets are larger and not as efficient as equity markets, there is ample opportunity for portfolio managers to add value through active security and sector selection. Put another way, passive fixed income strategies are virtually impossible to implement, given the large number of total issuers. Benchmark indexes may also exclude certain bonds that could be advantageous to purchase from a return perspective while still providing liability-hedging properties.

Ultimately, the most important evidence to consider is results. Over multi-year periods, many active fixed income managers have consistently outperformed their passive benchmarks. Based on Cambridge Associates’ database, 97% of managers have outperformed their benchmarks over a ten-year (or longest available) period. Additionally, many have accomplished this while maintaining similar or lower volatility than the benchmark. In other words, skilled active managers have consistently added alpha without creating additional portfolio risk.

Not All Active Fixed Income Strategies Are Created Equal

Most active fixed income managers look to avoid uncompensated tracking error relative to their benchmark, which is typically the Bloomberg Barclays US Long Credit Index. 5 Instead, managers aim for outperformance while keeping the volatility comparable to the benchmark.

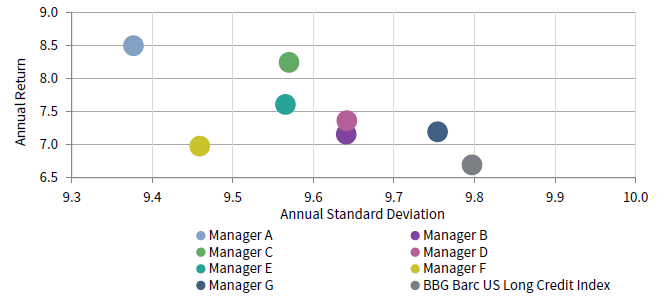

Figure 1 depicts a sample group of active fixed income managers, with varying degrees of outperformance between April 2016 and March 2021—some by considerable margins. The top manager outperformed by 180 bps annually over the five-year period, while some of the more conservative managers outperformed by 30 bps to 50 bps over the same period. In all cases, standard deviation of the performance was below the benchmark, indicating that volatility was well-managed and the managers did not produce additional risk in an asset allocation context.

FIGURE 1 ACTIVE FIXED INCOME MANAGERS EXHIBIT BENEFICIAL

RISK/RETURN CHARACTERISTICS

April 1, 2016 – March 31, 2021 • Percent (%)

Sources: Bloomberg Index Services Limited and Cambridge Associates LLC.

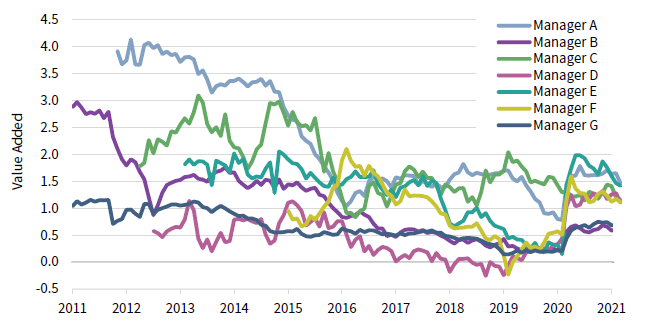

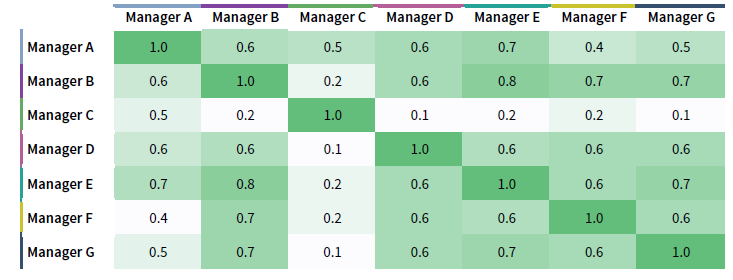

In Figure 1, the pure alpha generating abilities of these managers appears strong and consistent, but Figure 2 demonstrates that it can vary. This variance results from the tendency of fixed income managers to generate their value-add in different ways relative to other managers. Some are better at security selection, while others may be better at sector allocation. For some, allocations may be more quantitatively based, while others may be more qualitative. These differences show up over time in the correlation of returns in excess of the benchmark, as depicted in Figure 3. Lower figures (or lighter shades of green to white) indicate that excess returns are less correlated.

FIGURE 2 ALPHA GENERATION STRATEGIES FOR FIXED INCOME MANAGERS CAN VARY

January 1, 2011 – March 31, 2021 • Value-Added (%) Relatvie to BBG Barc Long Credit • Rolling 3-Yr Period • USD Terms

Sources: Bloomberg Index Services Limited and Cambridge Associates LLC.

Note: Data for each manager begin with the first year available.

FIGURE 3 DIFFERENT VALUE-ADD METHODS IMPACT RETURNS IN EXCESS OF BENCHMARK

April 1, 2016 – March 31, 2021 • Correlation of Excess Returns vs BBG Barc US Long Credit Index

Sources: Bloomberg Index Services Limited and Cambridge Associates LLC.

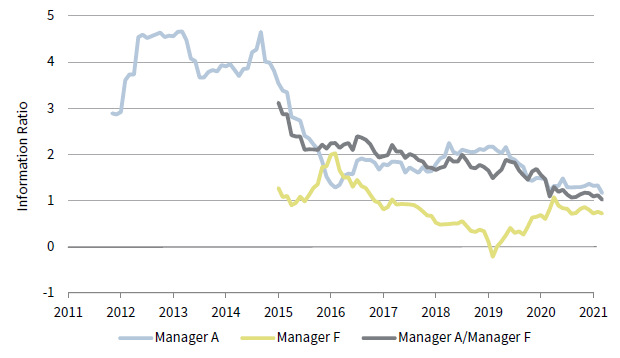

Creating a portfolio of different active fixed income managers with different strategies may aid portfolios more than relying on just one manager. For example, consider a simple portfolio composed of two active fixed income managers with equal capital allocations, but different approaches to portfolio management. The different strategies help lower the portfolio’s tracking error and create a more stable return pattern. As a result, the portfolio has a more stable—and potentially higher—information ratio, as depicted by the Manager A/Manager F line in Figure 4. This can enable a plan sponsor’s fixed income portfolio to maintain alpha generation with lower volatility to the plan’s liability while also reducing manager selection risk.

FIGURE 4 A PORTFOLIO OF DIFFERENT ACTIVE FIXED INCOME MANAGERS HAS A

MORE STABLE INFORMATION RATIO

March 31, 2011 – March 31, 2021 • Rolling 3-Yr Period

Sources: Bloomberg Index Services Limited and Cambridge Associates LLC.

Note: Data for each manager begin with the first year available.

Defining the Active Advantage

Fixed income, and particularly investment-grade credit, is an important part of defined benefit pension portfolios. It helps protect funded status and matches many of the pension plan liability characteristics. It can also offer ample opportunity for managers to add alpha, which is beneficial as plans become better funded. In terms of historical performance, active management in this space has proven itself over time, as most fixed income managers have consistently demonstrated an ability to generate value-add over their respective benchmarks while mitigating additional portfolio risk.

Being able to effectively select managers and size them appropriately in a portfolio is no simple task, but if done correctly, can add valuable funded status improvement and help plan sponsors reach their objectives more quickly and effectively. Investors cannot replicate these results with passive strategies alone. Having a sound understanding of the underlying mechanics of how each manager operates is crucial, since past performance is not indicative of future results. Actionable knowledge about managers, their investment methodologies, and investment team can only result from effective research.

Plan sponsors should not discount the potential for actively managed fixed income to provide alpha and mitigate portfolio risk. Done effectively, active fixed income can help plan sponsors more easily maintain pension plans on their balance sheets and allow for risk transfer to take place in a timely and less costly manner.

Katherine Brophy also contributed to this publication.

Footnotes

- While this paper focuses mainly on long-duration credit strategies, similar results can be achieved with intermediate or more broad-based credit strategies.

- Hibernating refers to maintaining the pension plan on the plan sponsor’s balance sheet for the indefinite future while terminating refers to complete transfer of liabilities to an insurance company.

- While the recent American Rescue Plan Act allows for more smoothing in the liability amounts used to determine contribution requirements, other liabilities measures, such as those for calculating Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation premiums, are still exposed to interest rate risk.

- This scenario assumes 60% of the portfolio is invested in long/intermediate credit managers.

- The Bloomberg Barclays US Long Credit Index measures the performance of investment-grade, US dollar–denominated, fixed rate, taxable corporate and government-related debt with at least ten years to maturity. It is composed of a corporate and a non-corporate component that includes non-US agencies, sovereigns, supranationals, and local authorities.