VantagePoint: Asia Opportunities Amid Shifting Geopolitics – Part II

The shifting geopolitical realities between the United States and China have already impacted trade and investment flows. In this two-part series of VantagePoint, we review this reality and consider investment implications alongside those of other key factors—such as domestic structural developments, macroeconomic conditions, and valuations. In Part I, we focused on opportunities in China specifically. In this companion piece, we discuss investment opportunities beyond China.

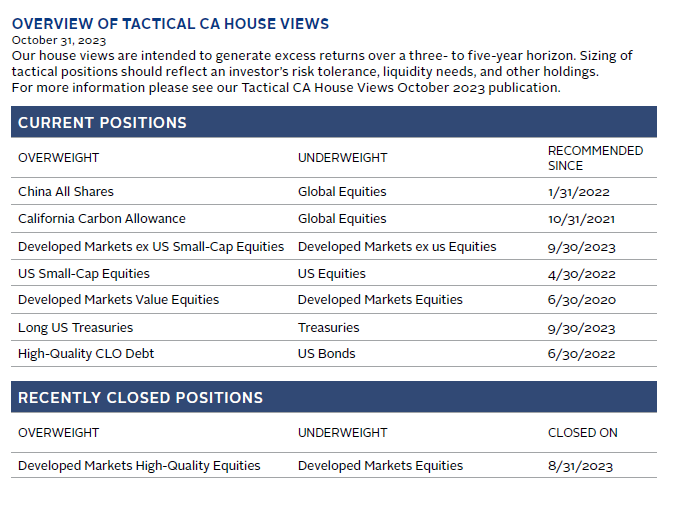

In sum, China remains an important destination for investor capital, while geopolitical realities are creating additional investment opportunities elsewhere in Asia. We recommend modest overweights to Chinese public equities relative to global equities, as cheap valuations compensate for the risks. We take a more cautious and selective approach toward venture capital (VC) due to longer-term risks, especially the uncertainty associated with US policies to discourage investment in China and restrict access to advanced technology. We see promising macro developments across much of Asia, particularly in India, Japan, and Southeast Asia (also referred to as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations [ASEAN]). 1 That said, valuations keep us neutral on public equities in India and Japan, although we view Indian VC and Japanese buyouts offering more appeal today. For ASEAN, the macro backdrop looks attractive, but the limited opportunity set poses implementation challenges today.

India: Long-Term Bullish, Neutral for Now

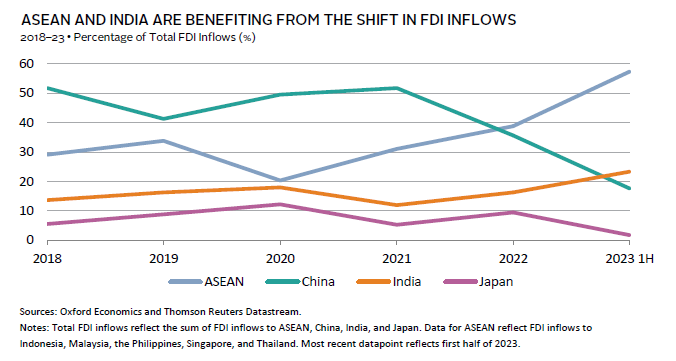

India’s relatively compelling economic backdrop has garnered investor attention. India’s economy is now the third largest in Asia and fifth largest globally, and despite slowing global growth, its projected GDP growth for fiscal year 2024–25 remains strong at north of 6%. And unlike China, India’s population is relatively young and fast growing. These factors, combined with a series of business reforms and government incentives over recent years, have improved the landscape for foreign investments and led to a gradual rise in foreign direct investment (FDI), including investments from US tech companies such as Google and Apple. While there is some political uncertainty over the stability of these reforms ahead of India’s 2024 general elections and Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s re-election, current opinion polls remain in his favor and would suggest continuity for now.

Indian equities outperformed global equities in 2022, as global central banks aggressively tightened monetary policy in response to surging inflation, while the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) did not have to tighten as much because India’s inflation remained largely in line with historical levels. As a result, consumer confidence and domestic activity were strong, and domestic purchases of Indian equities reached a record high. Further, given India’s economy and market are domestically oriented relative to other Asian markets, they have been sheltered from slowing global growth and trade. Economic growth projections for India remain resilient, and foreign capital has rotated back into India in 2023 on the back of stronger investor sentiment.

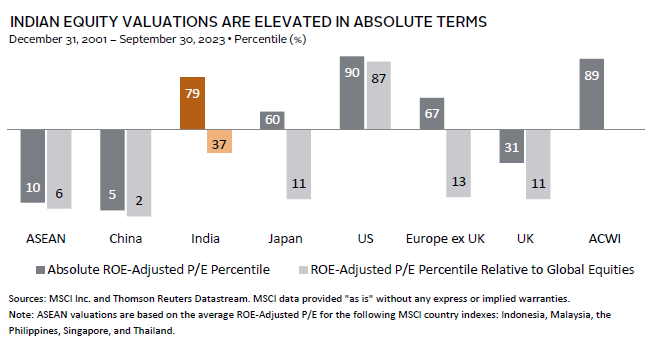

Given recent performance, valuations for Indian equities remain expensive relative to their own history and broader EM equities, although they still trade below their historical average relative to DM equities. Earnings growth expectations are also very high, which, taken together with elevated valuations, increases the downside risks of disappointment. And while the RBI has been on an extended pause since February 2023, upside risks to inflation arising from volatile food prices and higher oil prices could drive the central bank to further tighten policy, which could weigh on the equity market.

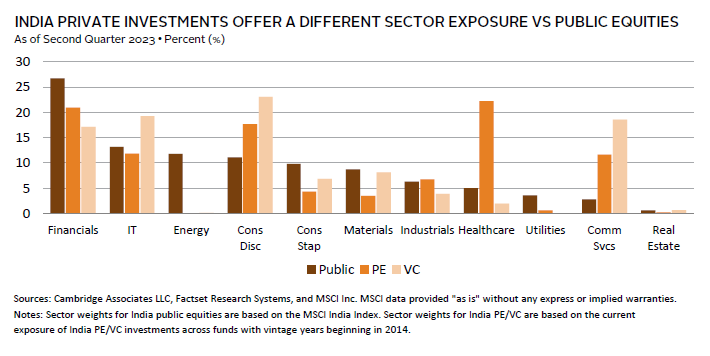

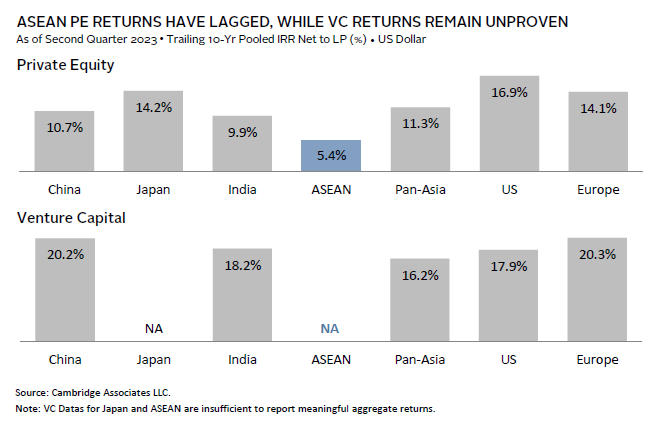

Indian private investments, particularly Indian VC, are more attractive in capturing the longer-term opportunities arising from shifting demographics, increased digitalization of the market, and the growth in demand for consumer services (e.g., e-commerce), business services (e.g., software applications), and financial services (e.g., financial mobile apps). Trailing ten-year returns for Indian VC have been comparable to US VC in USD terms, albeit lagging Chinese VC. However, return prospects have improved with the strengthening of manager expertise, an increase in exit channels (e.g., local capital markets, NASDAQ, financial sponsors, and strategics), and a buildup in the track record of exits. Valuations have also corrected from their 2022 highs, which, taken together with the strong macro fundamentals, create an attractive entry point for a ten-year VC investment strategy. Indian private equity (PE) offers less appeal as the manager opportunity set is less deep compared to Indian VC. In addition, the difference in sector exposures (e.g., PE focuses on brick-and-mortar retail, finance companies, and hospitals) results in lower target returns, which, after accounting for INR depreciation, makes the market less attractive relative to Indian VC.

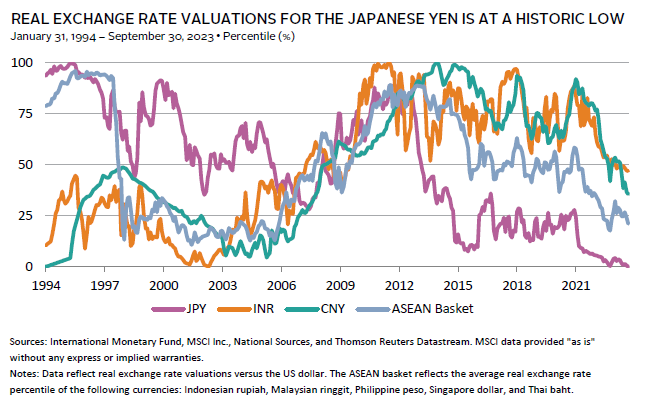

A key consideration when investing in India is the currency. Over the past three decades, the rupee has depreciated by around 3% to 4% annually on average versus the US dollar, in line with the spread in relative inflation between the United States and India. The rupee is also sensitive to movements in oil prices as India is a net importer of oil. With oil prices rising that could add to inflationary pressures in India, there may be additional downward pressure on the rupee in the near term. However, if the Federal Reserve and other major central banks begin cutting rates, this may provide some support to the currency, especially since real exchange rate valuations for the rupee versus the US dollar are not at overvalued levels, and the spread between global and Indian inflation may be narrower going forward.

Overall, India is set to benefit from domestic structural improvements, as well as current US-China geopolitical tensions, but there are some near-terms risks, given stretched valuations and economic overheating. Furthermore, India will need to capitalize on the current optimism by maintaining its pro-business reforms and political stability. For public equities, this leaves us neutral relative to the broad market. Given the improved long-term outlook, we would seek to overweight India should valuations materially improve. We are more constructive today on Indian VC, given the appealing sector focus and improved valuations.

ASEAN: The Stars Have Aligned, but Implementation Is Challenging

Like India, ASEAN is another market facing tailwinds from positive demographic changes and the global shift in supply-chain diversification from China. Currently, the region seems to be a key beneficiary of US-China tensions, gaining export share in the United States at the expense of China, but simultaneously seeing a rise in Chinese imports and investments. FDI inflows to the region increased by more than 50% in 2021–22 from 2019–20 levels. While Singapore continues to see the bulk of inflows, countries such as Vietnam have seen a rise in manufacturing investments, including some capital from Chinese companies looking to reduce labor costs and diversify their own manufacturing base. Meanwhile, FDI inflows to Indonesia also remain high, driven by mining industry investments.

Despite the positive macro backdrop, valuations for ASEAN equities (as proxied by the MSCI AC ASEAN Index) remain low, which is in part due to the current composition of the domestic equity market. ASEAN equities are meaningfully underweight tech, for which valuations have generally run up amid the previous low interest rate environment, and are overweight cyclical sectors, with close to 60% of the index made up of banks, industrials, and real estate companies. ASEAN’s sector composition resulted in strong earnings growth and outperformance relative to other Asian markets in 2022. However, relative earnings growth expectations have rolled over and relative performance reversed YTD, reflecting concerns over the export-oriented and cyclical nature of the market amid slowing global growth and trade. Yet, lower starting equity valuations provide a cushion, and ASEAN equities have more upside potential when the global economic cycle turns back up. Furthermore, ASEAN currencies also appear undervalued in real terms, and currency appreciation could help boost returns for investors, particularly if the Fed and other major global central banks begin to ease.

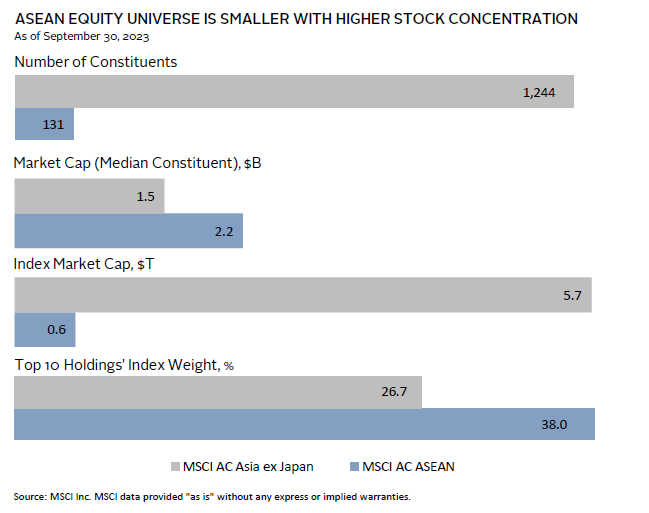

A challenge when investing in ASEAN equities is the smaller investable universe and the market’s higher stock concentration. This could gradually improve over time with capital inflows and as the markets deepen. But for now, the narrower opportunity set is also reflected in the limited number of dedicated ASEAN implementation options—both passive and active—that are available, making it difficult to meaningfully overweight this market directly via ASEAN mandates. Further, Vietnam, which has grown as a share of ASEAN’s GDP (11%) and exports (19%) over the past decade, is classified as a frontier market and not a part of the MSCI ACWI or MSCI ASEAN Index. At $30 billion, the MSCI Vietnam Index would only account for 5% of the MSCI AC ASEAN Index and 0.5% of the MSCI AC Asia ex Japan Index market cap if included.

In theory, the sector focus of private investments in ASEAN should better leverage the secular trends arising from the region’s growing population and increase in consumer demand for goods and services. When aggregated, the size of ASEAN’s GDP is comparable to that of India. However, the heterogeneous nature of the underlying economies has posed a challenge for managers. For instance, market dynamics in Indonesia are very different from those in Thailand, limiting scalability of businesses. Growth/buyout returns in ASEAN have lagged those of their Asia counterparts over the past ten years. For VC, the maturity of portfolios and track record of returns still need time to be realized. For instance, some managers have attractive internal rates of return, but distributions have been limited and performance is concentrated in a few deals and a few funds. Further, ASEAN VC exit routes are comparably fewer and investment opportunities are concentrated in a few key markets, such as Indonesia, resulting in high competition for deals. As a result, private market valuations may not be as depressed as public markets would suggest.

Over time, the influx of capital and talent (both globally and from China) could strengthen the entrepreneurial and manager ecosystem within ASEAN and improve future returns and deepen the opportunity set. However, in the near term, ASEAN PE/VC remains less attractive compared to other Asian or global markets and faces implementation challenges.

Overall, we see ASEAN as that rare combination of positive macro backdrop with attractive valuations, but the small size of the public markets and limited dedicated implementation options create some challenges for global investors to meaningfully increase exposure to the region. As a result, for now we think investor are better served gaining exposure to ASEAN via broader Asia mandates in public and private markets rather than dedicated exposure, at least until the manager opportunity set deepens.

Japan: Is the Sun Rising Again?

Japan is another market that is now on investors’ radars for different reasons than India and ASEAN. While there is an expectation that Japan will benefit from the geopolitical shift in supply chains away from China and the need for increased manufacturing capacity globally, Japan has yet to see a meaningful pick-up in annual FDI inflows or a meaningful increase in its export share to the United States and Europe. The renewed interest in Japan in part stems from the market’s relative resilience over 2022, alongside increased optimism that its economy may now be seeing a structural shift, with rising nominal wages and higher inflation driving a virtuous cycle of increased spending and investments, and, in turn, higher corporate profits and wages. New rules by the Tokyo Stock Exchange released in 2022 and 2023 to further enhance corporate governance and capital efficiency have also led to increased shareholder buybacks and improved the outlook for shareholder returns.

Since December 2021, Japanese equities have outperformed global equities in local currency terms, in large part due to the divergence in the Bank of Japan’s (BOJ) monetary policy versus other major central banks. With interest rates in Japan remaining low while having risen dramatically elsewhere, this has led to a sharp decline in the yen that boosted the overseas earnings and export orders of Japanese companies. Year-to-date, the market was also supported by a surge in foreign equity inflows. That being said, the weakness in the yen implies outperformance over the MSCI ACWI in USD terms has been modest, at 2.9 cumulative percentage points since December 2021.

The recent support for Japanese equities from a weaker yen and low rates could fade if the BOJ needs to tighten policy in the face of high inflation, especially at a time when other central banks are at or near the end of their tightening cycles. Higher inflation is also weighing on domestic consumption, while the weaker outlook for global growth is another risk, given the equity market’s overweight to the industrials and consumer discretionary sectors. Japan’s real GDP growth forecast for 2024 remains muted at 1.0%, and corporate earnings growth expectations have rolled over.

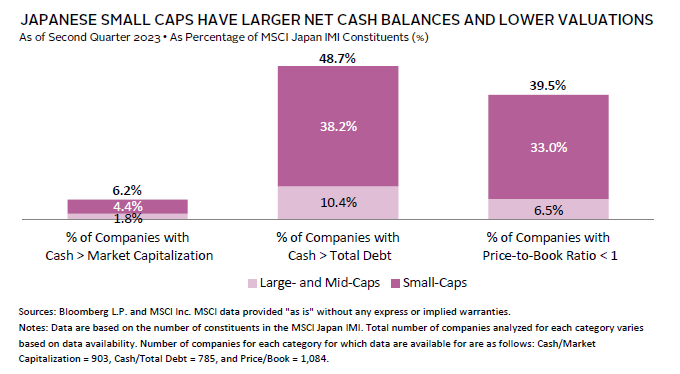

Valuations also may not offer a sufficient cushion against downside risks. Given the recent rally, the MSCI Japan Index is fair-to-expensive across the valuation metrics we track, although it still trades at a discount to global equities for which valuations are even higher. However, there is a long tail of smaller and somewhat illiquid companies in Japan that still trade at below–book value valuations and some with cash balances larger than their debt or even market cap that are often cited as evidence of Japanese equities being “cheap.”

As such, we remain neutral on Japanese equities broadly relative to the global equities. We would not want to be underweight today and think investors are better served looking at strategies less sensitive to broad Japanese market beta. One such area is activist managers, which could better capitalize on ongoing corporate reform initiatives to generate value. Small-cap Japanese equities may also benefit from corporate reform. Our newly initiated modest tactical overweight to DM ex US small-cap equities relative to their mid- to large-cap cousins is overweight Japanese small-cap equities when implemented with MSCI indexes. Within private markets, the VC market in Japan is underdeveloped with very limited options for foreign investors. However, the buyout market is attractive with established manager options available. Buyout managers are finding opportunities are increasing amid a wave of corporate succession deals arising from Japan’s aging demographics and other corporate actions are becoming more common (take-privates, conglomerate divestments/spinouts). Return prospects for Japan buyouts remain positive, given significantly lower borrowing costs and structural changes that are set to improve ROE and capital efficiency. While we are concerned about a reversal in the yen weighing on the overall market in the near term, fundamentally the currency is very cheap and likely to appreciate over the coming years, which should benefit long-term investors in such strategies.

In sum, uncertainty over the BOJ’s policy path creates near-term risks, particularly if the central bank moves to meaningfully tighten policy in the face of weakening domestic growth. That said, long-term investors should benefit from the structural reforms and increased focus on shareholder returns from corporate Japan, as well as a cheap currency and increased fund flows.

Conclusion: Expand Your Asia Investment Lens Aperture, but Mind the Valuations

As discussed in Part I of this series, the trade and financial decoupling between the United States and China is occurring faster than anticipated. The United States is unlikely to change its strategic policies toward China anytime soon (regardless of who wins the upcoming 2024 elections), while China’s shifting ideological focus from economic development to national security and self-sufficiency is also unlikely to change, although China is capable of abrupt shifts in policy when needed.

These geopolitical realities create additional investment opportunities in Asia, as China is unlikely to continue to receive the lion’s share of global investment flows into the region, despite the large size of its economy. Investors should expand the aperture of their investment lens to include Asian equity opportunities beyond China.

While we are concerned about public market valuations in India and Japan in the near term, these markets will likely see increased capital flows over time given ongoing positive structural changes at home. As such, we remain neutral relative to policy or market benchmark weights today and would prepare to overweight should valuations improve materially. We are positive on India VC and Japan buyout strategies today (as well as Japan small caps and activist strategies targeting these companies).

ASEAN is perhaps the biggest economic winner from the shifting of supply chains from China, and public equities and currencies currently appear undervalued. However, the small size of local capital markets and heterogenous economies makes investment implementation challenging, though this may continue to evolve over time and deserves monitoring. Investors seeking dedicated investments in the region must recognize the concentration and illiquidity inherent in the market, which may be best navigated through broader Asia strategies, both public and private.

The wider focus on Asia does not imply there are no attractive investment opportunities in China. Indeed, we think investors willing to overweight Chinese public equities relative to global equities will benefit as current relative valuations are depressed enough to offer potential outperformance should short-term sentiment toward China shift amid signs of more aggressive policy actions to support the economy.

Regarding China PE/VC, we think investors need to be very selective, given the shifting dynamics and opportunity set. We do not see a near-term thaw in the frozen fundraising cycle for China PE/VC until there is clarity on how the US executive order will be implemented and managers and investors have time to digest and adapt to the new rules. Hard-tech deals in sensitive sectors may simply shift toward domestic investors and non-US investors willing to invest in RMB fund vehicles. Meanwhile, USD capital will be focused on VC investment in other sectors and strategies such as buyouts and growth equity that face less geopolitical hurdles. Less capital chasing deals may result in better entry valuations and opportunities for investors (both US and non-US) willing to tolerate the uncertainty and headline risk in China. At the same time, the shifting geopolitical landscape creates other investment opportunities in Asia that deserve a closer look.

Celia Dallas, Chief Investment Strategist

Aaron Costello, Regional Head for Asia

Vivian Gan, Associate Investment Director, Capital Markets Research

David Kautter also contributed to this publication.

About Cambridge Associates

Cambridge Associates is a global investment firm with 50 years of institutional investing experience. The firm aims to help pension plans, endowments & foundations, healthcare systems, and private clients implement and manage custom investment portfolios that generate outperformance and maximize their impact on the world. Cambridge Associates delivers a range of services, including outsourced CIO, non-discretionary portfolio management, staff extension and alternative asset class mandates. Contact us today.

Index Disclosures

MSCI AC ASEAN Index

The MSCI AC ASEAN Index captures large- and mid-cap representation across 4 emerging markets countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand) and 1 developed markets country (Singapore). With 131 constituents, the index covers approximately 85% of the free float–adjusted market capitalization in each country.

MSCI AC Asia ex Japan Index

The MSCI AC Asia ex Japan Index captures large- and mid-cap representation across 2 of 3 developed markets countries (Hong Kong and Singapore; excluding Japan) and 8 emerging markets (EM) countries in Asia. EM countries include: China, India, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Thailand. With 1,244 constituents, the index covers approximately 85% of the free float–adjusted market capitalization in each country.

MSCI All Country World Index (ACWI)

The MSCI ACWI captures large- and mid-cap representation across 23 developed markets (DM) and 24 emerging markets (EM) countries. With 2,947 constituents, the index covers approximately 85% of the global investable equity opportunity set. DM countries include: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. EM countries include: Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Czech Republic, Egypt, Greece, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Korea, Kuwait, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, the Philippines, Poland, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates.

MSCI Indonesia Index

The MSCI Indonesia Index is designed to measure the performance of the large- and mid-cap segments of the Indonesian market. With 22 constituents, the index covers about 85% of the Indonesian equity universe.

MSCI Japan Index

The MSCI Japan Index is designed to measure the performance of the large- and mid-cap segments of the Japanese market. With 235 constituents, the index covers approximately 85% of the free float–adjusted market capitalization in Japan.

MSCI Malaysia Index

The MSCI Malaysia Index is designed to measure the performance of the large- and mid-cap segments of the Malaysian market. With 32 constituents, the index covers about 85% of the Malaysian equity universe.

MSCI Philippines Index

The MSCI Philippines Index is designed to measure the performance of the large- and mid-cap segments of the Philippines market. With 14 constituents, the index covers about 85% of the Philippines equity universe.

MSCI Singapore Index

The MSCI Singapore Index is designed to measure the performance of the large- and mid-cap segments of the Singapore market. With 22 constituents, the index covers approximately 85% of the free float-adjusted market capitalization of the Singapore equity universe.

MSCI Thailand Index

The MSCI Thailand Index is designed to measure the performance of the large- and mid-cap segments of the Thailand market. With 41 constituents, the index covers about 85% of the Thailand equity universe.

MSCI Vietnam Index

The MSCI Vietnam Index is designed to measure the performance of the large- and mid-cap segments of the Vietnamese market. With 51 constituents, the index covers approximately 85% of the Vietnam equity universe.