Gender Lens Investing: Impact Opportunities Through Gender Equity

Not since the feminist movement of the 1960s has there been more focus on gender inequality. Although interest in this subject has been building for several years, more recent events have focused the world’s attention. From the decision to allow women to drive in Saudi Arabia to the Women’s March on Washington, from the United Kingdom’s new regulations on the publication of gender pay gap data to the surge of the “Me Too” movement, politicians, companies, and many individuals are realizing that this wave is powerful. And it is powerful for investors as well.

Gender lens investing is an investing approach that deliberately incorporates a desire to make a difference in the lives of women and girls, 1 while meeting the risk/return objectives appropriate for an institutional portfolio. 2 Many mission- and impact-oriented foundations and family offices have long tried to address gender inequities through their grant-making and philanthropic activity. Increasingly, these actors are turning to their investment portfolios to tackle these challenges, as the field of impact investing grows and the investment landscape deepens.

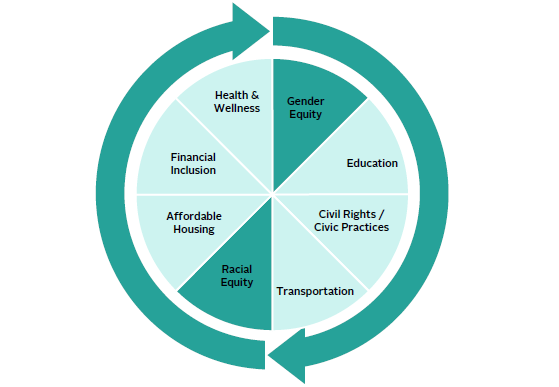

Gender equity is one of many interests that an investor may have and often overlaps with other investor mission-related and impact objectives. Gender equity is one of eight social equity themes (Figure 1) that are core to creating a socially equitable society and where investors can deploy capital. It also cuts across other social equity themes, similar to racial equity, as outlined in our recent publication, “Social Equity Investing: Righting Institutional Wrongs.”

In this brief paper, we present: a review of gender equality and its impact on economic growth; a case for gender lens investing as an alpha engine; an overview of gender lens investing; and an outline of opportunities for investment. With a gender lens framework, investors can positively impact gender imbalances via their portfolio management choices; this paper provides tangible investment themes and implementable strategies.

FIGURE 1 EIGHT CORE EQUITY ISSUE AREAS

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Gender Equality and Growth

Improving the lives of women and girls is not just an altruistic pursuit; it can also boost economic growth, bolster well-being to all stakeholders, and create compelling opportunities for investment. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), higher gender inequality is associated with lower economic growth. Gender wage gaps directly contribute not only to income inequality, but also to inequality of opportunity, such as access to education, health services, and financial markets. 3

If increased participation in the workforce leads to higher economic activity, then there is a strong case for providing educational services to women and ensuring they have equal access to basic needs (i.e., clean water, safe sources of fuel and electricity, stable/safe housing, and proper medical care). According to a McKinsey study, achieving full gender equality in the workforce could boost global annual GDP by $28 trillion by 2025, with the scale of that increase exceeding the size of the Eurozone economy today. 4 However, at the current rate of progress, the World Economic Forum estimates that it will take 100 years to close the overall gender gap. 5

Despite what may feel like slow progress, women are a substantial and growing force in the global economy. It is estimated that by 2020, women will control $72 trillion of wealth, or 32% of all global wealth, up from 30% currently, and they already have influence over 70%–80% of all consumer purchasing. 6 As a result of these shifts in spending and wealth, companies are beginning to realize the need to create quality products that appeal to the female population.

The Financial Impact of Women in the Workforce

Women remain underrepresented in the workforce. They continue to be a minority on company boards and in the C-suite. As of 2017, only 16% of board seats and 4.4% of CEO roles across Russell 3000® companies were held by women. A US Census Bureau study finds that compensation for women in the United States averages 21% less than for men holding comparable roles. Over a lifetime, that wage gap is projected to cost college-educated American millennial women more than $1 million in earnings. 7

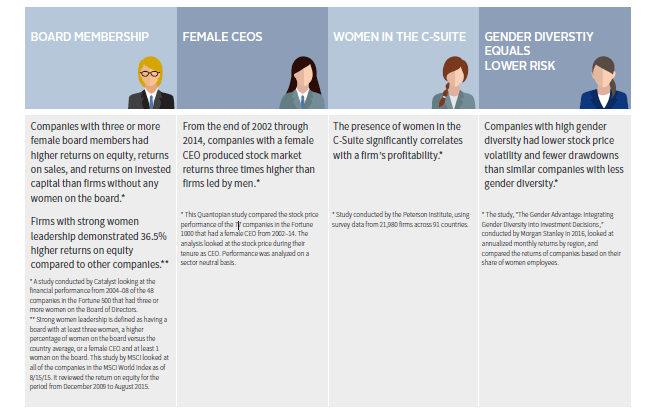

But what impact do women in the workforce have on company returns? Over the last decade, researchers have been trying to answer this question definitively. Although some of the data are mixed and sample sizes of some studies are small, the evidence suggests that empowering women in the workforce positively impacts society and the economy, and can also boost a company’s profitability and return on investment.

Why might this be true? Research indicates that the average collective intelligence of a team or company increases when women are incorporated, as a result of more perspectives being included and more blind spots being avoided. These different perspectives stem from a participant’s distinctive background, skill set, networks, and experience. In addition, when more women are at the table, performance levels rise. 8 Figure 2 describes the positive financial impacts companies experience when more women are in the workforce.

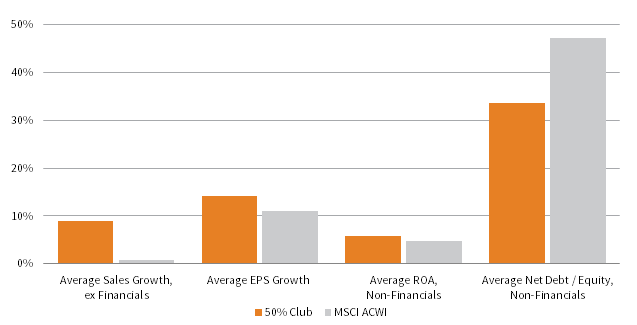

In 2016, the Credit Suisse Research Institute issued a report 9 that supported gender diversity’s improvement of business performance. Analyzing companies where women occupied 50% or more of the leadership positions, Credit Suisse found that sales growth, earnings per share growth, and return on assets were all higher than for the broad universe of companies, and that debt/equity levels were lower (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2 THE CASE FOR GENERATING ALPHA THROUGH WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT INVESTING

FIGURE 3 FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE OF THE 50% CLUB

2009–15

Source: Data sourced from Credit Suisse Research Institute’s 2016 study “The CS Gender 3000: The Reward for Change.”

Note: The “50% Club” refers to firms where women occupied 50% or more of leadership roles.

Boston Consulting Group and MassChallenge, a US-based global network of accelerators, cited that start-ups founded or co-founded by women generated 10% more revenue than male-founded start-ups over a five-year period, despite receiving significantly less than half as much investment. The revenue return on investment for female-founded start-ups exceeds that for male-founded start-ups by two-and-one-half times. 10 Similarly, a study conducted by the US Small Business Administration (SBA) showed that the performance of venture capital firms improves as the ratio of investment in women-led businesses (WLBs) increases, despite WLBs receiving less funding, being smaller, and being in slower growth industries. 11

In the area of microfinance—providing financial services to underserved communities and individuals—recent data show that 60%–70% of clients are women. Many microfinance institutions have a declared goal to lend mostly to women. Women tend to be more reliable in repaying the loans and more likely to invest the capital to improve the well-being of their families.

Have Female Portfolio Managers and General Partners Demonstrated a Performance Advantage?

Some research indicates that women investors are more patient and churn portfolios less often than male peers. According to one study of retail investors, men traded 45% more frequently than women, ultimately reducing the net returns of male investors by 2.7 percentage points (ppts) per year versus 1.7 ppts for women. 12 In addition, female clients of a European robo-adviser were less likely to withdraw money from their investments in periods of market volatility, probably improving their performance over the long term. 13

In 2015, Morningstar reviewed the ten-year performance record of nearly 8,000 mutual fund portfolio managers (PMs). Only 9.4% were women, and of those, only 37 women had a ten-year continuous track record. Women exclusively managed 1.9% of all assets across all funds; they also co-managed, as part of a team, 24.1% of all assets. Morningstar discovered that the performance record of funds managed exclusively by women rivals that of men. 14

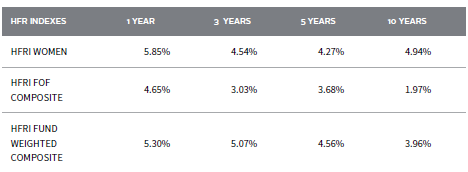

According to Hedge Fund Research (HFR) data, the HFR Women Index, which currently comprises 37 female hedge fund managers, outperformed the HFRI Fund of Funds Composite Index on trailing one-, three-, five-, and ten-year periods ended September 14, 2018 (Figure 4). While performance results for the HFR Women Index trail the HFRI Fund Weighted Composite Index over moderate periods, the HFR Women Index comes out on top over ten years.

FIGURE 4 HFR INDEX RETURNS

As of September 14, 2018

Source: Hedge Fund Research, Inc.

Note: Hedge Fund Research data are preliminary for the preceding five months.

Understanding Gender Lens Investing

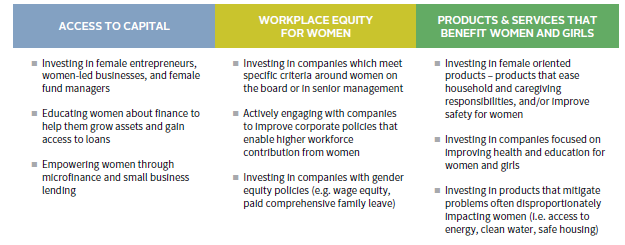

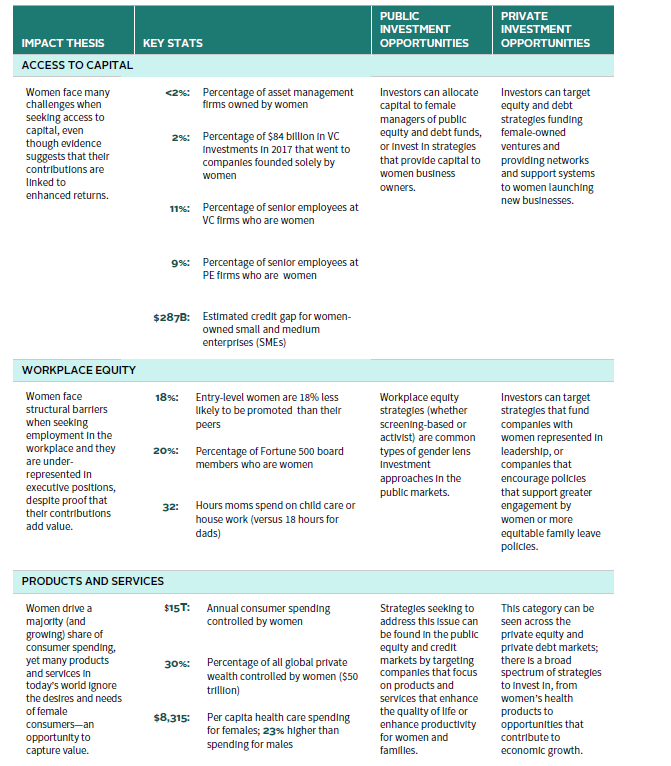

Gender lens investing is still a new concept for many investors. Although studies regarding the importance of women in the global economy date back at least two decades and the term gender lens investing has been around for more than a decade, broader interest in the sector has only recently gained significant momentum. There are many different ways gender lens investing can be defined, and each definition comes with a range of interpretations and assumptions. Various participants in the field have taken a broad approach to defining the term, since it can apply to all genders and incorporate many different factors in the investment decision making process. We have identified three primary pillars of gender lens investing: increased access to capital for women, workplace equity, and the development of products and services that benefit women and girls. These categories are not mutually exclusive; some investment strategies may focus on a combination of the three. Figure 5 provides some examples that fall within each pillar.

As gender lens investing expands, it will ultimately promote a culture that extends beyond counting women in the workplace toward one that views investing in women as a societal norm.

FIGURE 5 GENDER LENS INVESTING PILLARS

Putting it into Practice

Fewer dedicated investment strategies currently exist than for some other impact investment sectors. However, investor interest in gender lens strategies has increased in recent years. A growing amount of data have encouraged a range of investment managers to incorporate a gender lens framework into products dedicated to the advancement of women and girls, consistent with the expectation of a market rate of return.

These opportunities can be found across asset classes (both fixed income and equity strategies in private and public markets) and in each of the three gender lens pillars. As of this publication, Cambridge Associates monitors approximately 30 strategies in the public markets that are specifically labeled as gender lens investments, with $1 billion in aggregate assets. According to data compiled for Project Sage, a research initiative conducted by the Wharton Social Impact Initiative, $1.3 billion had been committed to 58 private investment funds with a gender lens focus as of October 2017, ranging in size from $1 million to $400 million. 15

Investment Opportunities

Public Equity. Public equity managers target gender equity goals through strategies including positive or negative screens, active engagement, and/or targeted investment solutions focused specifically on the advancement of women and girls. Within public equities, portfolio managers and investment firms that employ gender lens investing typically use data to screen the universe of investable stocks or employ active engagement to promote workplace equity across their portfolio holdings (Figure 6). The screening criteria differ across strategies. For example, some may require that a company have a female CEO; another may require a firm to have one or more women on the board of directors; and yet another may require a certain number of women in senior management positions. Like any investment mandate, the specific set of screens used to define the investment universe will have different implications on the type of impact and size of the investable universe. In addition to simple screens, public equity strategies can also target companies that provide services benefitting women and families. For instance, a company such as Unilever provides consumer health products globally and has worked to empower women throughout its value chain with innovations such as women-owned microbusinesses focused on last-mile distribution in rural, developing markets.

FIGURE 6 EXAMPLES OF PUBLIC INVESTMENT STRATEGIES

Investors can also make a positive impact on women by actively engaging with their investment managers, even if the manager does not yet offer dedicated gender lens strategies. Investment managers can actively vote proxies and engage with management teams at their portfolio companies to promote greater inclusion and/or women’s rights in the workplace, regardless of the investment mandate. 16

Public Credit. Corporate or municipal credit strategies that use a gender lens, like many public equity gender lens strategies, can proactively seek to invest in the debt of companies or municipalities advancing an equitable workplace and/or providing products and services that benefit women and families. They can also avoid investments in organizations with policies that inhibit gender equity. Examples include loans to support affordable multifamily housing, municipal issuance that is used to fund health care facilities, and/or public services in the community.

Private Equity/Credit. In private markets, investors are often able to achieve more targeted impact based on their areas of interest. Opportunities exist across venture capital private equity funds, debt funds, holding companies, and collaborative angel funds.

Access to capital is a common strategy in the private markets. Some general partners are funding female entrepreneurs, since they are underfunded compared to men and are more likely to align their portfolio companies’ products and services to the arguably underserved global population of women and girls. Depending on the strategy, access to capital can mean very different things (Figure 7). One manager might provide equity capital to female entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley, while another might make loans to women living in rural communities in developing markets to help them start a small-scale business. Workforce equity can be pursued through a range of private equity and venture capital strategies that only invest in companies where women hold leadership positions or provide benefits that enable women’s increased workforce participation. Products and services that benefit women and girls are also a common focus, ranging from improving women’s and children’s health, education, and economic opportunity to enhancing women’s lives with access to clean water and energy.

FIGURE 7 EXAMPLES OF PRIVATE INVESTMENT STRATEGIES

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Portfolio Implementation

Implementing gender lens objectives in an investment portfolio can be accomplished in a range of ways; investors should recognize that there is no universal solution for all portfolios. In developing an implementation strategy investors should consider several factors to meet their specific gender lens impact objectives, such as its role in the portfolio and associated financial requirements and available investment opportunities. It is important for investors when incorporating gender lens into their investment portfolios to communicate why they are doing so.

Gender Lens Impact Objectives

Investors seeking to align their portfolios with gender lens objectives should start by clearly identifying which pillars are of greatest importance. The level of alignment can also vary between investment strategies and impact goals, generally taking one of three forms: focused, holistic, or neutral. Some investors might use just one strategy, or a combination of multiple strategies in their efforts to meet their gender lens objectives as the investment universe develops.

Focused Impact. These strategies align closely with an investor’s gender lens goals and generate measurable impacts and outcomes. Although the investment landscape is constantly evolving, focused impact strategies are available across asset classes and across the return spectrum. A venture capital fund that supports products to improve the lives of girls would be classified as a focused impact strategy. Some investors use dedicated carve-outs to meet focused impact objectives by investing a portion of their portfolio in strategies that have a direct impact on the lives of women and girls.

Holistic Impact. These strategies align with gender lens goals to a lesser degree, but still have a positive effect on women and girls through indirect channels. Opportunities for holistic impact exist in all asset classes; however, we see investors employ this approach primarily in the public markets, where the number of managers incorporating gender as one of several environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors has expanded tremendously (Figure 8). Furthermore, investors have the opportunity to engage managers to consider more specific gender impact objectives as they assess various companies. Some investors use an integrated approach to meet holistic impact objectives. For example, an institution might deliberately seek strategies managed by women alongside their traditional investment portfolio.

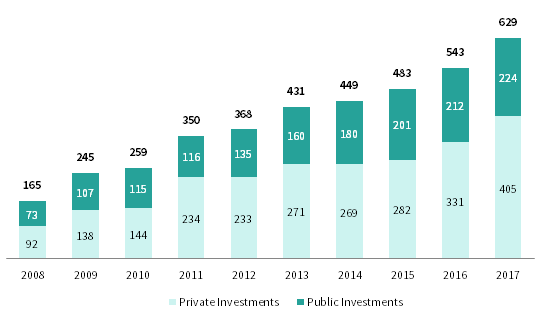

FIGURE 8 MANAGERS INCORPORATING ESG IN PRIVATE AND PUBLIC INVESTMENTS

2008–17

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Notes: These numbers reflect the managers in our database that have been identified by Cambridge Associates as actively integrating ESG and/or impact as a core and material part of their investment strategy. The identification process is systematic, but subject to judgement. Specific composition of managers may vary each year as firms consolidate, close, or shift their approach. The methodology for identifying managers may change over time to reflect market conditions and best practices.

Neutral Impact. These strategies seek to avoid investments that conflict with an investor’s gender lens goals. Depending on the investor’s gender equity priorities, a passively screened public equity strategy that avoids pornography, weapons, or other industries disproportionately affecting women and girls might be considered a neutral impact approach; however, the industry screening would not necessarily promote workplace equity or other goals. Notably, though some investors may view a neutral impact strategy as benefiting women less than more proactive strategies, others may view this method as a powerful tool to signify their opposition while retaining investment flexibility. We encourage investors to be diligent and dig into underlying holdings and portfolio companies to ensure that the portfolio is not acting against its stated impact objectives.

Portfolio’s Financial Objectives

Investment portfolios serve a range of functions for different enterprises, so it is important to consider financial attributes such as risk/return objectives and liquidity and income parameters when integrating gender impact. For example, multi-generational investment pools may want to consider early-stage venture capital strategies focused on boosting health outcomes for women and children, but these investments would be inappropriate for investors that require high levels of current income and liquidity.

Investment Opportunity Set

Although we expect that the growing prominence and focus on gender lens investing will yield a more robust opportunity set for both new entrants and existing players, the current universe of dedicated institutional quality investment opportunities remains limited. When developing a gender lens strategy, we encourage investors to build flexibility into their policy, allowing for the likely evolution of the opportunity set.

Due to the complexity of the field, fully understanding the opportunity set and portfolio implementation will take time, and not all solutions or structures will be applicable or relevant for all investors. Investors should be aware of the opportunities and limitations of their own capital pools as they seek to create implementation strategies that optimize both impact and financial objectives.

Conclusion

Gender lens investing is quickly gaining traction amongst different types of investors, offering the potential to align portfolios with impact or mission goals, address gender inequality, and generate returns attributed to the faster economic growth associated with gender equity. Investment managers are responding to this demand by launching new gender lens investment strategies. Perhaps even more importantly, interest in gender lens investing is helping to facilitate a growing body of research examining the role of women in the global economy. These trends create a unique and compelling opportunity for investors to integrate gender lens strategies into their portfolios and to capitalize on the economic opportunity created by gender equity.

APPENDIX DETAILED GENDER LENS ISSUE MAP

Sources: Bank of America Private Wealth Management, Boston Consulting Group, Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services, Deloitte, International Finance Corporation, McKinsey & Company, Pew Research, PitchBook, and Preqin.

Deborah Christie, Managing Director

Additional Resources

For those seeking to become acquainted with basic concepts of impact investing, including investment principles, goals, and return expectations, we recommend some of our prior publications as resources.

“Social Equity Investing: Righting Institutional Wrongs” (2018)

“Navigating the “Alphabet Soup” of Mission-Related Investing” (2017)

“Considerations for ESG Policy Development” (2017)

Footnotes

- To be clear, gender considerations impact all aspects of life and types of investments, and they can be dynamic and fluid. Gender is not an exclusionary lens but is rather inclusionary, as the benefits of gender lens investing positively affect every member of society, including men and gender non-conforming people. While this paper may often refer to women and girls, we acknowledge that some investors may define gender differently and have varying objectives.

- Gender lens investing can be incorporated into a range of risk/return profiles through the use of different strategies. This paper will focus exclusively on market-rate return strategies—strategies that have the same expected risk/return profile as the broader universe of strategies with similar mandates. We do acknowledge, however, that some investment strategies employed to meet gender lens objectives may explicitly have concessionary return objectives. These will not be addressed in this paper

- Please see Sonali Jain-Chandra et al., “Women, Work, and Economic Growth,” International Monetary Fund, February 15, 2017.

- Please see Sandrine Devillard et al., “The Power of Parity: How Advancing Women’s Equality Can Add $12 Trillion to Global Growth,” McKinsey Global Institute, September 2015.

- Please see Ricardo Hausmann et al., “The Global Gender Gap Report 2017,” World Economic Forum, November 2, 2017.

- Please see Bridget Brennan, “Top 10 Things Everyone Should Know About Women Consumers,” Forbes, January 21, 2015.

- Please see Heidi Hartmann and Jeff Hayes, “Wage Gap Will Cost Millennial Women $1 Million Over their Careers,” Institute for Women’s Policy Research, April 10, 2018. The data reflect the difference between the median annual earnings of women and men who worked full-time, year-round.

- Please see Vivian Hunt et al., “Diversity Matters,” McKinsey & Company, February 2, 2015, a study conducted on 366 public companies across a range of industries in Canada, Latin America, the United Kingdom, and the United States, and Scott Berinato et al., “What Makes a Team Smarter? More Women,” Harvard Business Review, June 1, 2011.

- Please see Julia Dawson et al., “The CS Gender 3000: The Reward for Change,” Credit Suisse Research Institute, September 2016. The CS Gender 3000 proprietary database includes nearly 3,400 companies across all industries in all countries.

- Please see Katie Abouzahr et al., “Why Women-Owned Start-ups Are a Better Bet,” Boston Consulting Group, June 6, 2018. The study analyzed 350 random companies over a five-year period, 258 of which were founded by men and 92 of which were founded or co-founded by women. According to BCG, the findings were statistically significant, even after ruling out factors such as education levels of the entrepreneurs and quality of pitches.

- Please see JMG Consulting, LLC & Wyckoff Consulting, LLC for the SBA, “Venture Capital, Social Capital and the Funding of Women-Led Businesses,” April 2013. This study analyzed 2,500 venture capital firms with investments in 18,900 portfolio companies from 2000 to 2010. WLBs are defined as companies with at least one woman on the management team, which included 41% of the portfolio companies studied.

- Please see Brad M. Barber and Terrance Odean, “Boys will be Boys: Gender, Overconfidence, and Common Stock Investment,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol 116, no. 1 (February 2001): 261–292.

- This study was conducted by Nutmeg Saving and Investment Limited, with results cited by Dani Burger, “When Markets Go Crazy, Women Are More Likely to Keep their Cool,” Bloomberg, July 3, 2018.

- Morningstar updated their gender study in March 2018 and came to the same conclusion that men and women deliver equally competitive fund performance. Please see Erin Davis and Laura Pavlenko Lutton, “Fund Managers by Gender: Through the Performance Lens,” Morningstar, March 8, 2018.

- The Wharton Social Impact Initiative was founded in 2013 to strengthen the positive impact of business and capital markets. Project Sage is one such initiative that seeks to track venture capital with a gender lens.

- Several investor groups claim success with using letter-writing campaigns to increase the number of women on boards. In 2008, only 14% of the S&P 500 board seats were held by women. Today that number has risen to 22%. Of course, such campaigns are undoubtedly only one driver of the increased gender diversity. Please see Savita Subramanian et al., “Women: The X-Factor,” Bank of America Merrill Lynch, March 7, 2018.