Determining the Right Price: A Wealth Management Cost Framework for Families

Families of wealth are always curious about wealth management costs and often want to benchmark those expenses against their peers. Costs are an important consideration when devising an overall wealth management strategy. What is the right price and how is it determined? In some cases, a lower cost approach may not be sufficient to do the job of wealth management well. Indeed, a family may have good reason for paying a higher price, including superior service and better results. Two of the most notable factors that can increase wealth management costs are the use of sophisticated wealth structuring strategies—often as part of tax efficiency and estate planning—and the execution of alternative investment strategies like private equity and hedge funds. In all instances, cost should be commensurate to the value delivered to the family.

This paper presents a framework that families with substantial diversified portfolio investments can use to evaluate the costs of managing their wealth. The analysis is broken into four parts: evaluation of costs; factors that can cause costs to fluctuate; key questions to ask when evaluating wealth management costs; and best practices. While the paper presents a range of cost estimates drawn from real world examples, each family’s wealth management cost formula is different. The focus here is to provide families with insights and tools for determining how to meet their unique service requirements and goals at a reasonable cost.

Evaluation of Costs

Families addressing the issue of cost should start by evaluating their total wealth management expenses. Two high-level inputs—investment costs and non-investment costs—make up total wealth management expenses (Figure 1).

In accordance with a family’s service requirements and goals, investment and non-investment costs may be linked to a family office—if there is one—or incurred through third-party service providers.

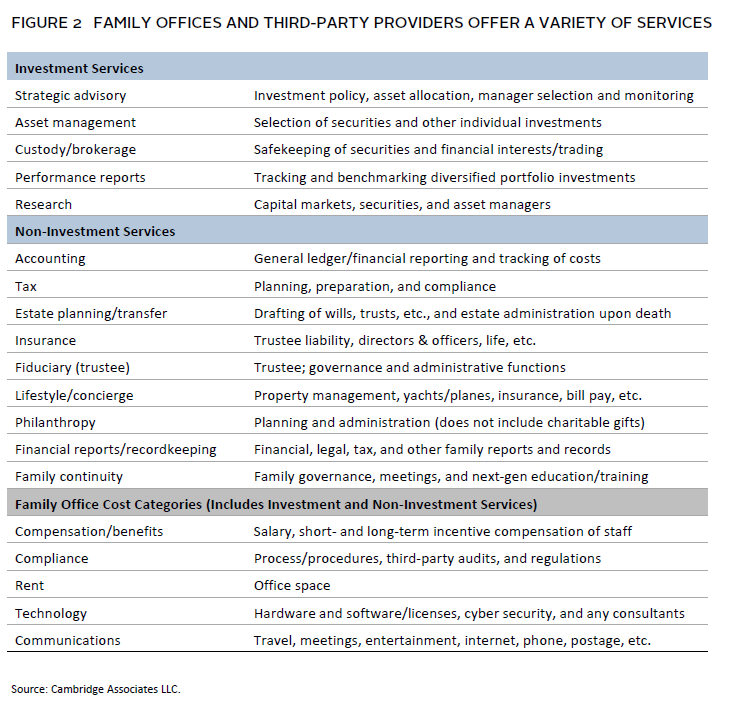

Costs also consist of a wide range of more granular line items including asset management, next-gen education, financial reporting, tax compliance, trustee fees, recordkeeping, property management, and family retreats, among others. Often families require broader and more varied services than they initially expect. Figure 2 inventories the wealth management services that families should consider as part of a cost analysis. In many cases, a family office will also serve as a gatekeeper and coordinator of all wealth management activities.

Both a family office or a third-party provider can be used to perform designated investment and non-investment functions. The notion of “build or buy” comes into play when families consider whether to construct their own wealth management capabilities and individualized services inside a family office, or to outsource some or all of these tasks to a third-party provider. Some of these costs may also be shared. For example, there may be some accounting services performed by the family office and other accounting services performed by a third party. In this scenario, the two cost buckets should be allocated accordingly.

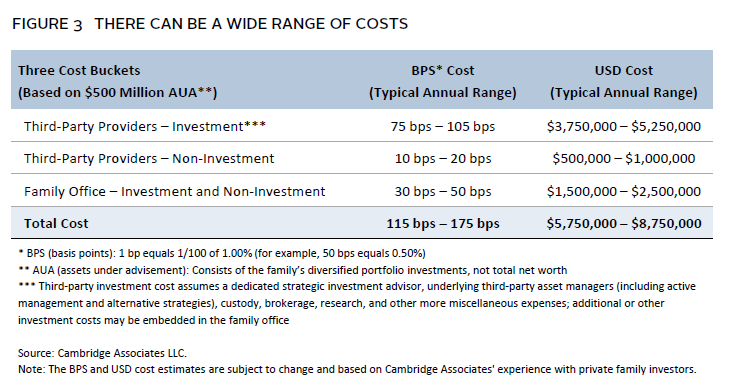

Figure 3 illustrates typical ranges for annualized investment and non-investment costs and their allocation between a family office and third-party service providers. Total cost is usually more than 100 basis points (bps) (1.00%) of investable assets, and, in Figure 3, the range is between 115 bps and 175 bps. For wealth owners with substantial assets, there can be a wide range of cost levels that fluctuate in relation to individual family circumstances, and a good number will be outside the ranges above. Measuring cost in terms of basis points compared to investable assets—not total net worth—is common practice.

As Figure 3 indicates, investment services typically represent a high percentage of overall wealth management costs—characteristically 50% or more of total expenses. Asset management is inevitably the largest line item within investment services and can include fees charged by underlying fund managers selecting securities. This range of costs is largely driven by asset allocation and incorporation of more expensive strategies, such as hedge funds and private equity. Accounting and tax services are large components of non-investment costs. Legal costs are usually lower by comparison, but can spike episodically, such as when a family restructures its assets or engages in intensive estate planning. When evaluating certain costs, they should be normalized to account for any short-term aberrations. For instance, a family overhauls its estate planning in a particular year, with legal fees amounting to $250,000. If the usual annual run rate for legal fees is $50,000, the lower number can be used to normalize the data for benchmarking against peer offices.

If the standalone cost of a family office is being evaluated, the allocation of services between the office and third-party service providers should be closely considered. A family office with an in-house investment team and a peer office that outsources this function to a third-party provider will have a substantially different family office cost profile. For example, a family office with an in-house chief investment officer, two investment analysts, and a data analyst can top $1,000,000 in annual compensation, benefits, and overhead costs—before accounting for other outsourced investment functions. The cost of services delivered by a family office should be considered on a standalone basis and added together with those of third-party advisors to gain a more comprehensive view of total expenditures.

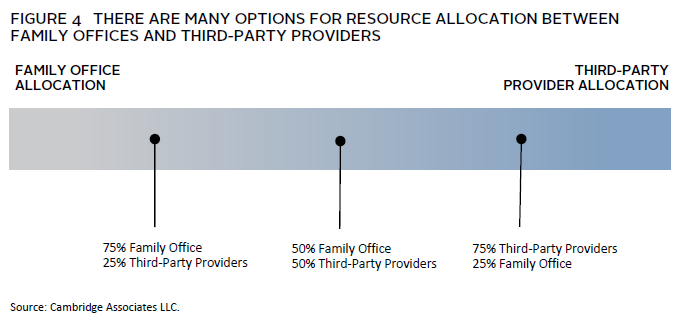

Inevitably, families of wealth operating a family office engage and pay third-party advisors to assist in performing certain services. No family office performs 100% of the services. Figure 4 shows three examples of the degrees of outsourcing versus insourcing.

The degree to which services are performed by the family office or delegated to third-party providers can vary. A high degree of outsourcing, say allocations of 75% or more, pushes costs to third-party providers and should figure in a family’s cost analysis. Due to the customized nature of the family office, it is generally assumed to be more expensive than engaging with only third-party providers. Families who are considering whether to establish a family office should conduct a cost/benefit analysis to identify and evaluate their needs against these additional expenses. Of course, when deciding to “build versus buy,” cost is not the only consideration—integrity, trust, experience, track record, and other criteria also should be considered.

Why Do Costs Vary So Much?

Two important characteristics to keep in mind when assessing wealth management costs are the complexity of the required services and economies of scale at play.

Complexity

Some factors, such as the total number of family households or financial entities, have a fairly straightforward impact on costs. Generally, the more households and entities, the higher the cost. However, other factors can add to overall cost in less obvious ways. A higher number of accounting and tax entities, for example, often requires more sophisticated tax and estate planning design, advanced monitoring, and more robust reporting, which will lead to higher costs. Likewise, the use of more complex alternative investments in a family’s portfolio will lead to higher fees compared to traditional active and passive strategies.

Figure 5 presents a simplified, hypothetical example of how larger and more complex wealth management requirements can substantially drive up a family’s total cost. In this example, both families have the same level of portfolio investments, but one is responsible for an additional $1,500,000 in costs when comparing cost of wealth management fees of $3,200,000 versus $4,500,000, representing a 33% premium.

Expanded financial reporting for intricate ownership structures, compensation for those providing investment governance, and next-gen education are examples of an expanded wealth management remit leading to higher costs. With benchmarking costs, families should consider the full range of services they require, as their impact on price can be dramatic. In many cases, more complicated, higher cost arrangements are worthwhile if they can help a family optimize wealth management solutions and help them achieve their investment goals.

Economies of Scale

When buying wealth management services, there are often also important economies of scale at work, which refers to the potential cost savings that become available as the size of the wealth increases. For example, savings from economies of scale are often available when a family buys legal, investment, or accounting and tax services, whether through a family office or third-party providers. When a family aggregates its purchasing power, the benefits can take the form of higher quality advice, more experienced and accomplished wealth advisors, and lower fees.

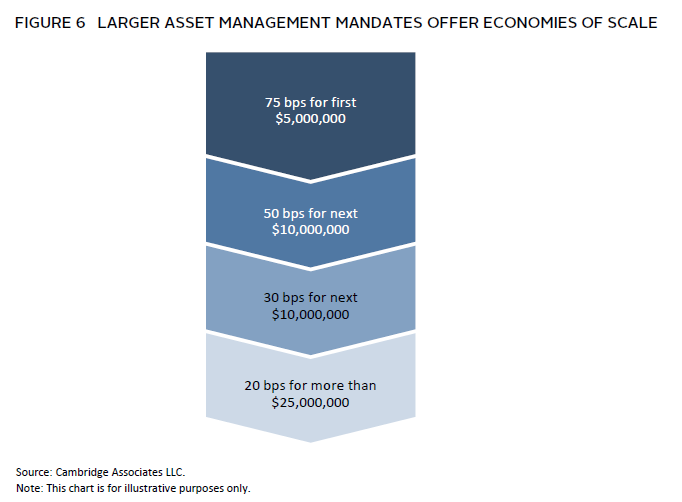

One of the easiest examples to quantify economies of scale is the fee differential for larger versus smaller asset management mandates. Figure 6 presents a hypothetical tiered fee structure for a third-party long-only equity manager.

When applying this hypothetical fee schedule, an investment of $15,000,000 with the equity manager would have an effective fee of 58 bps per year. An investment of $50,000,000 using the same fee schedule would be subject to an effective fee of 34 bps per year. In dollar terms, of course, the larger investment would cost more—$170,000 versus $87,500. In percentage terms, the cost of managing a $50,000,000 investment represents about half the price of a $15,000,000 investment mandate.

Key Questions

Answering some key questions can help families determine the best way to budget and evaluate their wealth management costs. An initial set of questions can help families identify and frame the issues:

- Is there a defined, disciplined budgeting process?

- Are costs informed by the family’s service requirements and objectives?

- What is the total cost of wealth management (top-down)?

- What are the individual investment and non-investment line-item costs (bottom-up)?

- Will total wealth management costs be reviewed on a regular basis?

Once threshold issues have been identified and framed, more nuanced questions can be addressed:

- How will the evaluation and analysis of costs incorporate the impact of complexity?

- What is a reasonable cost? How do costs compare to the quality and value of the services?

- What metrics and tools will be used to measure and evaluate costs?

- Are costs rationally allocated between the family office (if any) and third-party service providers?

- Are costs reasonably allocated between financial entities, wealth owners, and beneficiaries?

Families can and should adjust the questions to fit their situation, but the list above is a good starting point.

Best Practices

The following best practices can help guide families as they evaluate their wealth management costs:

- Strategic View: Connect costs to the broader strategic plan for the wealth management program—be intentional about costs and map them to the family’s service needs and goals.

- Governance: Address costs strategically at the governance and ownership levels and do not delegate to management or those executing components of wealth management.

- Disciplined Process: Compare projected annual budgets with actual annual budgets and conduct a cost/benefit analysis, including formal cost reviews and audits for vehicles such as a family office and entities holding financial assets.

- Recognize objective quantifiable costs (like investment performance net of fees) and more subjective non-quantifiable costs (such as the benefit of quality and independent advice).

- Benchmarking: Compare costs to closest peers and available benchmarks at least once every five years.

- Transparency: Provide transparency and communications about costs to all family members with an ownership or beneficial interest, as well as any other key stakeholders.

It is normal for families to incorporate best practices over time and after putting in place more basic processes to manage and measure costs.

Conclusion

Families can begin to evaluate their wealth management costs only after they have clarified their service requirements and goals in the context of their total wealth and investable assets. Asking the right questions and framing the issues go a long way to determining the right price and how costs should be viewed and managed. From there, families can better assess underlying costs for wealth management services, including any complexity factors and economies of scale. Weighing the total expense against the value of the services provided is critical, even if there is not always an objective, quantifiable way of doing so. Benchmarking costs against peers can be informative, but wealth management costs should ultimately be considered within the context of meeting a family’s service requirements and helping them to achieve their investment goals.

Charlie Grace, Managing Director, Family Enterprise Solutions, Private Client Practice