Revving Pension Plans’ Funding Engines

CONTENTS

Generating Returns Is Critical

Achieving Growth Returns Through Portfolio Construction

Fixed Income: Not Only a Liability Hedge

Growth Engine Opportunities

Conclusion

Generating Returns Is Critical

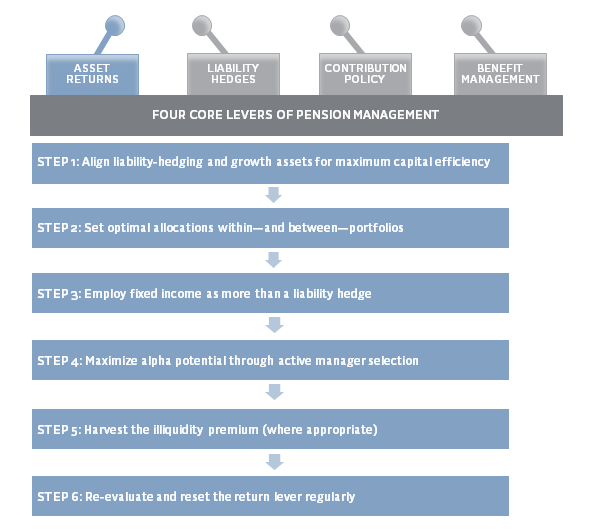

As discussed in “A Balancing Act: Strategies for Financial Executives in Managing Pension Risk,” plan sponsors have four primary levers with which to manage their DB plans and their impacts on corporate financials: contribution policy, benefit management, liability hedging, and return generation (Figure 1). The degree to which each lever is engaged depends on a number of plan sponsor–specific considerations. However, in most situations, plan sponsors will use all four levers, with the return generation lever playing a critical role in improving a plan’s funded status and maintaining a strong funded status once it is achieved.

Obviously, underfunded, open, and soft-frozen plans need higher asset returns. But generating excess returns relative to liabilities is important even for well-funded, hard-frozen plans as a means to offset future administrative expenses (such as PBGC premiums and actuarial fees) and unexpected liability increases due to mortality assumption changes or other adverse plan experience.

FIGURE 1 EMPLOYING THE RETURNS LEVER

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

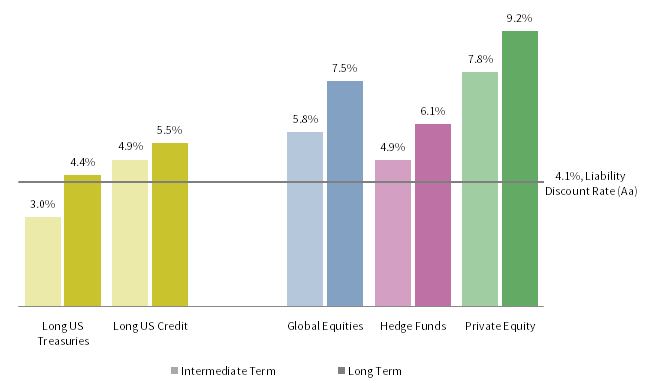

Unfortunately, securing these essential excess returns will likely be more challenging in the years ahead. Existing valuations, particularly in public and private equities, suggest future returns for traditional growth portfolios may be lower than historical averages (Figure 2). Thanks to recent increases in both Treasury yields and corporate bond spreads, liability discount rates are among the highest they have been in nearly five years. This means that global equities—the mainstay of pensions’ growth portfolios—have to work even harder to outperform the liabilities. So how, and with what risks, can plan sponsors achieve excess returns?

FIGURE 2 INTERMEDIATE- AND LONG-TERM EXPECTED NOMINAL RETURNS

As of December 31, 2018

Sources: Bloomberg Index Services Limited, Cambridge Associates LLC, FTSE Russell, Hedge Fund Research, Inc., and MSCI Inc. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: Intermediate-term capital market assumptions for fixed income are current yields on relevant market benchmarks; for all other asset classes, they are a ten-year forecast that explicitly models the current valuation of each asset class, the “fair” or average valuation of each asset class historically, and the estimated return associated with reverting to “fair value” over a ten-year period. These assumptions assume moderate real earnings growth, low corporate default rates, and a return from current values to fair value for equity multiples, government bond yields, and corporate credit spreads. Fair values are largely based on historical averages. Long-term capital market assumptions reflect a blend of ten years of intermediate-term capital market assumptions and 15 years of equilibrium capital market assumptions that focus on the fundamental risk and return characteristics of each asset class, based both on long-term data and capital markets theory, which is agnostic to the current market environment. Both approaches assume an inflation assumption of 2.5%. Expected returns are net of investment manager fees but not any other expenses. Liability discount rate reflects the FTSE Pension Liability Index (Intermediate).

Achieving Growth Returns Through Portfolio Construction

Determining how plan sponsors can achieve excess returns requires a comprehensive enterprise review that will analyze the plan’s liability structure and the plan sponsor’s objectives, balance sheet, and operational constraints, as well as establish key asset strategy parameters. Among others, these parameters include:

- A capital-efficient balance between liability-hedging assets (tasked with hedging changes in pension obligations due to changes in the discount rate) and growth assets (tasked with generating superior asset returns in excess of the discount rate);

- A more granular allocation within both liability hedging and growth assets;

- The appropriate amount of active manager risk (relative to the overall markets); and

- The degree of illiquidity risk a plan sponsor can assume.

Capital Efficiency

Given depressed growth asset return expectations, efficient capital allocation is paramount to outperforming the liabilities, while still effectively hedging liability–interest rate risk. Plan sponsors can accomplish both tasks by using the full toolkit of fixed income securities and associated derivatives (as opposed to only long-duration physical bonds). That is, a capital-efficient approach can hedge more liability interest rate risk with fewer dollars, thereby freeing up much-needed capital to pursue growth strategies. For example, by using Long Treasury STRIPS or Treasury futures in place of Long Treasuries, plan sponsors can achieve the same degree of liability hedging with 25% to 50% less capital.

Asset Allocation

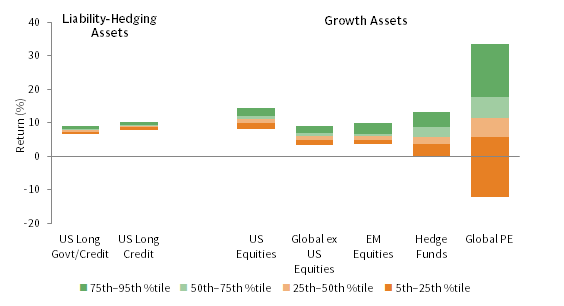

Once the appropriate balance between growth assets and liability-hedging assets has been optimized, plan sponsors may turn their attention to making asset allocation decisions within those portfolios. In doing so, plans should maximize excess return potential relative to funded status volatility, evaluating not only expected beta returns (Figure 2) but also the opportunity for manager value-add (Figure 3). Another key consideration is the interaction between asset classes, including the often underappreciated correlation between corporate bond spreads in the liability-hedging portfolio and public equities in the growth portfolio.

FIGURE 3 DISPERSION OF COMPOUND MANAGER RETURNS OVER 10 YEARS

As of September 30, 2018

Sources: Cambridge Associates LLC and eVestment.

Notes: Liability-hedging assets data are sourced from eVestment; Cambridge Associates data are used for all other asset classes. Returns for bond, equity, and hedge fund managers are average annual compound returns (AACRs) for the ten years ended September 30, 2018, and only managers with performance available for the entire period are included. Returns for private investment managers are horizon internal rates of return (IRRs) calculated since inception to June 30, 2018. Time-weighted returns (AACRs) and money-weighted returns (IRRs) are not directly comparable. Cambridge Associates LLC’s bond, equity, and hedge fund manager universe statistics are derived from CA’s proprietary Investment Manager Database. Managers that do not report in US dollars, exclude cash reserves from reported total returns, or have less than $50 million in product assets are excluded. Performance of bond and public equity managers is generally reported gross of investment management fees. Hedge fund managers generally report performance net of investment management fees and performance fees. CA derives its private benchmarks from the financial information contained in its proprietary database of private investment funds. The pooled returns represent the net end-to-end rates of return calculated on the aggregate of all cash flows and market values as reported to Cambridge Associates by the funds’ general partners in their quarterly and annual audited financial reports. These returns are net of management fees, expenses, and performance fees that take the form of a carried interest.

Active Management

Figure 3 demonstrates that the greatest active opportunities lie within growth asset classes. For example, the return differential between top quartile and median long-bond managers is 0.5% compared to 1.0% in global equities, 2.9% in hedge funds, and 6.5% in private equity. Still, plan sponsors should not ignore the opportunity to add value in liability-hedging assets, especially as these assets increase in size relative to growth assets.

Of course, the opportunity set is much wider in growth assets. Nowhere is this more true than among alternative investments, which also often exhibit a lower correlation and a lower beta relative to global equity markets, making them particularly attractive in today’s environment. That said, the appeal of alternatives may be tempered by their illiquidity, complexity, limited transparency, and higher management fees.

Illiquidity Risk

Alternatives may enable plan sponsors to achieve higher returns than those possible through traditional asset classes. However, in accessing these investments’ potential return lift, plan sponsors must take into account the different types of risk they may consequently incur, particularly illiquidity risk.

While plan sponsors within striking distance of a plan termination or a large risk transfer may need daily or monthly liquidity, many plan sponsors overestimate the amount of liquidity they need. In fact, open plans with an indefinite time horizon or frozen plans not destined for termination can benefit from illiquid private investments. And for all plans, hedge funds (which, though not liquid daily, rarely have lock-up periods longer than one year) can play a crucial role in reducing portfolio—and therefore funded status—volatility. This is especially true in down markets.

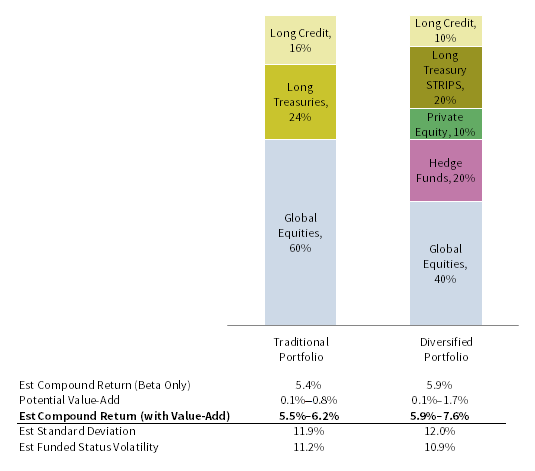

Putting It Together

For plan sponsors willing to invest the required resources in portfolio implementation, a capital-efficient, risk-diversified portfolio can significantly outperform a traditional pension portfolio. For instance, for an open plan that is 75% funded, replacing a portfolio of 60% global equities/40% long-duration bonds with one that has 70% allocated to diversified growth assets (including private equity and hedge funds) and 30% invested in efficiently implemented liability-hedging assets may moderately improve expected beta return and reduce funded-status volatility. More importantly, by including alternatives, the potential manager value-add increases significantly, making this option even more attractive (Figures 3 and 4).

FIGURE 4 SAMPLE PORTFOLIOS

As of December 31, 2018

Sources: Bloomberg Index Services Limited, Cambridge Associates LLC, FTSE Russell, Hedge Fund Research, Inc., and MSCI Inc. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: Expected return, risk, and funded status risk reflect intermediate-term capital market assumption. Assumed funded status is 75%, liability duration is 13.0 years, and liability discount rate is 4.1% (the liability discount rate reflects the FTSE Pension Liability Index–Intermediate). Funded status volatility accounts for unhedgeable liability risk. Potential value-add reflects no value-add for Treasuries and STRIPS, the difference between 25th to 50th percentile manager returns shown in Figure 3 and relevant indexes for public markets, and the difference between 25th to 50th percentile manager returns and the median manager return shown in Figure 3 for alternatives. The calculation accounts for average manager fees by asset class.

Fixed Income: Not Only a Liability Hedge

While the primary focus of the liability-hedging portfolio is to hedge liability interest rate and credit spread risks, plan sponsors should not ignore the opportunity to outperform the liabilities. But first, the liability-hedging portfolio needs to not underperform! To ensure this, liability-hedging assets (combined with growth asset returns) must earn a sufficient carry relative to the liabilities. In addition, liability-hedging assets need to avoid the impact of corporate bond downgrades and defaults, which adversely affect assets but not liabilities. Both of these requirements make active management essential.

Although the potential for manager value-add in credit is lower than in growth assets, plan sponsors should not leave this potential credit alpha on the table. As plans become hard-frozen and better funded, the need to generate excess returns relative to liabilities generally declines but does not go away entirely, as ongoing plan costs continue to accumulate. Because the liability-hedging portfolio also dominates the growth portfolio at that point, it is incumbent for these assets not only to hedge liability interest rate and credit spread risks, but also to serve as an incremental, yet important, source of growth.

In addition to relying on manager skill within investment-grade credit, plan sponsors can generate excess return in fixed income by allocating funds to alternative credit market segments that are still somewhat correlated to corporate bond spreads. These include high yield, bank loans, emerging markets debt, collateralized loan obligations, and private credit. 1 When sized appropriately and potentially combined with a Treasury futures overlay, alternative credit can generate higher yield and diversify existing corporate bond holdings without detracting from the liability-hedging objectives of the portfolio. Within alternative credit, private credit (which has more than tripled in size since 2007) may be particularly attractive. Its illiquidity is not as severe as that of private equity; many strategies provide ongoing cash flows, and the yield pick-up relative to corporate bonds is material. As with any illiquid and opaque strategy, comprehensive asset-liability modeling, manager research, and ongoing monitoring are critical.

Growth Engine Opportunities

From both expected return and potential manager value-add perspectives, global equities, private investments, and hedge funds form the growth engine of the pension strategy. In this section, we review the value and considerations associated with each of these investment types.

Global Equities

Global equities are usually the cornerstone of the growth portfolio. Although some degree of passive management is often appropriate (such as for plans that have large benefit outflows), active management of global equities—particularly publicly traded international and emerging markets equities—can be helpful.

While the differential between top quartile and median US, global ex US, and emerging markets equities managers is similar at approximately 1.0%, the dispersion is different in the top quartile: the difference between 5th and 25th percentiles is 2.3% and 2.2% for US and global ex US managers, respectively, but 3.3% for emerging markets managers. This is not surprising, since emerging markets equities are generally less efficient than their developed counterparts and, hence, present greater potential for alpha generation. Although many investors choose to invest passively in US equities, we believe active management is critical, given the potential need to protect against high valuations reverting back to more normal levels.

As with all investment decisions, plan sponsors should consider their risk appetite against the risk of each investment. Specifically, plan sponsors should devote experienced external or internal resources to conduct due diligence and ongoing monitoring on investment opportunities and determine appropriate sizing for investment managers, countries, and regions within the portfolio.

Private Investments

By including private equity, venture capital, and private real estate in growth portfolios, plan sponsors can significantly expand their investment opportunity set and potential for generating returns. Indeed, as the number of public equity stocks has fallen by nearly 50% since its peak in 1996 and as once-rare investment types, such as co-investments and secondaries, have become more common, private investments have become increasingly pertinent to a well-constructed and diversified portfolio.

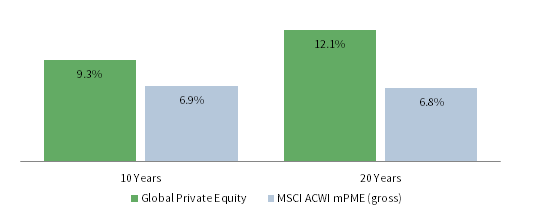

As discussed, for plan sponsors willing to lock up even a limited portion of their assets and take on the complexity of the asset class, private investments have the potential to increase portfolio returns significantly and offer multiple other attractive attributes. They have demonstrated outperformance versus public markets over appropriately long periods of time (Figure 5); private equity, for example, has outperformed its public market equivalent by 2.4% and 5.3% over 10 and 20 years, respectively, as calculated on a Cambridge Associates modified Public Market Equivalent basis. 2

FIGURE 5 PUBLIC VS PRIVATE EQUITY RETURNS

Sources: Cambridge Associates LLC and MSCI Inc. MSCI data provided “as is” and without any expressed or implied warranties.

Notes: Based on all global private equity (buyout, private equity energy, growth equity, and subordinated capital funds) funds tracked by Cambridge Associates that were active during the time periods analyzed. Returns for private investments are based on quarterly end-to-end internal rates of return, which are net of fees, expenses, and carried interest; analysis includes funds from vintage years 1998–2012. Cambridge Associates mPME methodology replicates private investment performance under public market conditions and allows for an appropriate comparison of private and public market returns. The mPME analysis evaluates what return would have been earned had the dollars invested in private investments been invested in the public market index instead. Total return data for the MSCI ACWI are gross of dividend taxes.

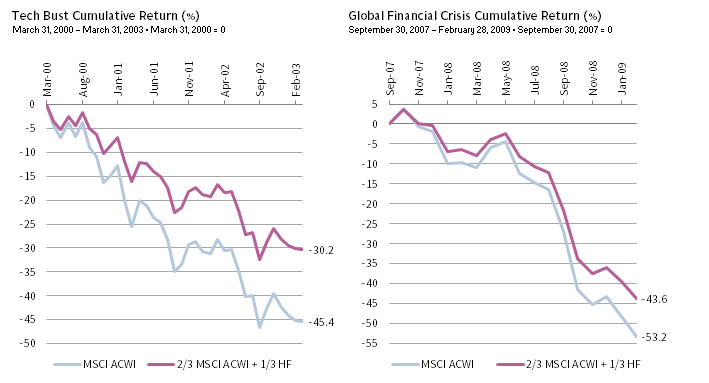

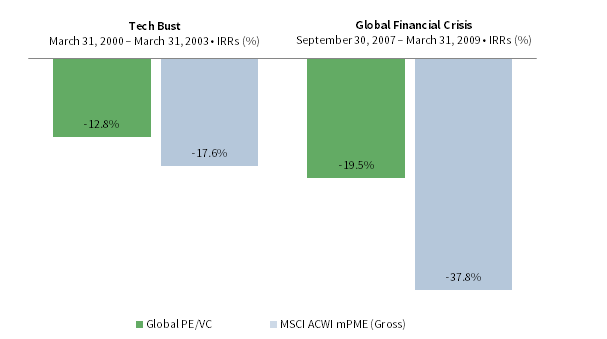

Private investments can also benefit the total portfolio by reducing portfolio volatility and, thus, funded status volatility. This is because private investments are valued on a quarterly basis, and the nature of the valuation process causes some stickiness in the portfolio (to the upside and the downside) over the long term. For example, the CA Global Private Equity/Venture Capital Index realized significantly smaller drawdowns compared to public equities during the 2000–03 tech bust and the 2007–09 financial crisis, outperforming by 4.8 and 18.4 percentage points, respectively, as calculated on a Cambridge Associates modified Public Market Equivalent basis (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6 PUBLIC VS PRIVATE EQUITY RETURNS DURING THE TECH BUBBLE AND THE GLOBAL FINANCIAL CRISIS

Sources: Cambridge Associates LLC and MSCI Inc. MSCI data provided “as is” and without any expressed or implied warranties.

Notes: Based on all global private equity (buyout, private equity energy, growth equity, and subordinated capital funds) and venture capital funds tracked by Cambridge Associates that were active during the time periods analyzed. Returns for private investments are based on quarterly end-to-end internal rates of return, which are net of fees, expenses, and carried interest. Cambridge Associates mPME methodology replicates private investment performance under public market conditions and allows for an appropriate comparison of private and public market returns. The mPME analysis evaluates what return would have been earned had the dollars invested in private investments been invested in the public market index instead. Total return data for the MSCI ACWI are gross of dividend taxes.

Current and future liquidity needs, informed both by the amount of time the plan sponsor intends to maintain the plan and by projected benefit payments and contributions, should help determine the sizing of and types of strategies within the private investments portfolio. Yet plan sponsors often shy away from private investments and sacrifice critical return potential by overestimating their liquidity needs or painting all private investments with the same illiquidity brush.

In fact, different kinds of private investments have different liquidity time horizon profiles, ranging from ten to 15 years for venture and buyout funds to as little as six to eight years for secondaries. The cash flow profile of private investments also can vary by strategy and vintage year, in part due to the ebb and flow of merger & acquisition activity and capital markets movements, again with venture and buyout funds generally having less predictable cash flows than private credit. Though exact cash flow planning for a private investment portfolio is not possible, informed pacing, as well as disciplined portfolio monitoring, can help plan sponsors manage these investments effectively.

In contrast to publicly traded equities and debt, there is no passive (or indexed) approach to private investing, the dispersion of manager returns is substantial, liquidation prior to fund wind down can be costly, and operational complexity is high. Therefore, extracting value from private investments requires skill in all stages of the investment process and calls for an experienced and well-resourced team of private investment professionals. Harvesting the return premium offered by private investments requires effective planning, ongoing manager due diligence and portfolio construction, vintage-year diversification, cash flow management between funds distributing capital and those calling it, and fund document legal review.

Of course, investing in private vehicles requires patience. Based on Cambridge Associates’ research, the typical private equity fund takes six to seven years on average to produce meaningful performance results. To realize long-term success, plan sponsors thus must be able to stay the course over the decade or more required to achieve mature performance.

Hedge Funds

Unlike public and private equity, which serve as primary drivers of returns, hedge funds can enhance total portfolio returns over the long term through diversification, lower volatility, and downside protection in sustained down markets. Despite the many challenges associated with hedge funds, introducing a well-designed hedge fund program into a holistic pension risk management strategy remains attractive, especially in the current environment, which has been punctuated by highly volatile global equity markets and a rising risk of a broad-based market drawdown.

As with private equity, plan sponsors should be extremely selective when investing in hedge funds, since, in aggregate, the hedge fund universe delivers little to no value relative to a simple stock/bond portfolio. Also, many funds charge high fees, employ excessive leverage, and provide little transparency. Of the approximately 8,000 hedge funds worldwide, we believe 5%, at most, merit institutional capital. As for the fees, liquidity, transparency, and leverage associated with hedge funds, these are legitimate issues that should be fully explored in the context of each strategy. Often they may be more surmountable, or have sufficient off-setting advantages, than is commonly believed.

Different types of hedge fund strategies can play various roles within a portfolio. Plan sponsors should consider the role that each strategy serves in the context of the plan’s total portfolio. For example, certain global macro and quantitative strategies present opportunities to generate uncorrelated returns, regardless of market direction, and decrease portfolio volatility. On the other hand, equity-linked strategies, such as equity long/short, have overall betas ranging from near zero to as high as approaching one and thus can be more market oriented. Finally, the fluid nature of certain hedge funds and their ability to actively manage exposures across instruments and opportunistically shift positioning toward less exploited areas can help protect portfolios.

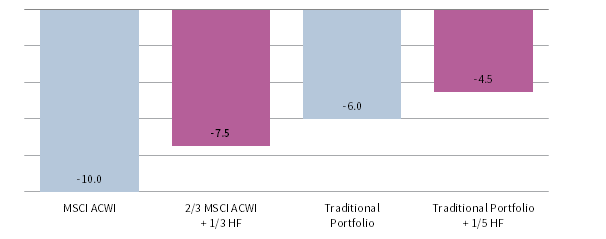

To illustrate this point, Figure 7 shows the impact of a hypothetical 10% global equity market correction on a traditional portfolio (60% global equities and 40% long-duration bonds) versus one that includes a 20% allocation to hedge funds. Under this scenario, the traditional portfolio falls by 6.0%, but a portfolio with the 20% allocation to hedge funds falls by just 4.5%. The smaller loss implies a smaller decline in funded status, protecting the plan at a time when plan sponsors are unlikely to be able to make additional contributions. Indeed, during two well-known “perfect storms,” the 2000–03 tech bust and 2007–09 financial crisis, diversifying a portion of the portfolio into hedge funds could have significantly reduced a plan’s growth assets—and therefore total portfolio and funded status—drawdown (Figure 8).

FIGURE 7 IMPACT OF A 10% GLOBAL EQUITY MARKETS CORRECTION

As of December 31, 2018 • Return (%)

Sources: Bloomberg Index Services Limited, Cambridge Associates LLC, MSCI Inc., and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: Hedge fund data are through March 31, 2018. Hedge fund returns shown are net of manager and CA fees. CA fees are estimated based on a model fee calculation using the highest CA fee schedule appropriate for the client type and service provided. The model fee deducted was equal to or greater than actual fees paid by that client to CA. Total return data for the MSCI ACWI are gross of dividend taxes prior to 2001 and net of dividend taxes thereafter. This exhibit uses the average performance of MSCI ACWI, Traditional Portfolio, and Traditional + Hedge Funds Portfolio during one-month periods where the MSCI ACWI returned less than -8% since 2000. Those average returns are then scaled to -10% MSCI ACWI returns for uniformity and to increase the size of the data set. Actual average returns over the one-month periods included in the analysis where -10.1%, -7.6%, -6.1%, and -4.6% for the MSCI ACWI, 2/3 MSCI ACWI and 1/3 HF, Traditional Portfolio, and Traditional Portfolio + 1/5 HF, respectively. Please see figure notes and the performance disclosure at the end of the publication for information about the portfolios and the hedge fund component.

FIGURE 8 GROWTH PORTFOLIO RETURNS DURING THE TECH BUBBLE AND THE GLOBAL FINANCIAL CRISIS

Sources: Bloomberg Index Services Limited, Cambridge Associates LLC, MSCI Inc., and Thomson Reuters Datastream. MSCI data provided “as is” without any express or implied warranties.

Notes: Data are monthly. Total return data for the MSCI ACWI are gross of dividend taxes prior to 2001 and net of dividend taxes thereafter. Hedge fund returns shown are net of manager and CA fees. CA fees are estimated based on a model fee calculation using the highest CA fee schedule appropriate for the client type and service provided. The model fee deducted was equal to or greater than actual fees paid by that client to CA. Please see figure notes and the performance disclosure at the end of the publication for information about the hedge fund component.

To be sure, in up markets, most hedge funds do not generate the same strong returns as equity markets. However, the downside protection, coupled with potential manager value-add, makes hedge funds compelling as a consistent allocation within the growth portfolio, aiding the overall portfolio over the full market cycle. In particular, capital preservation during bear markets enables low-beta/high-alpha hedge funds 3 to capture the long-term benefits of compounding returns. On the flip side, hedge funds have greater flexibility to increase exposure when valuations are cheaper and, hence, be positioned to better profit from downturns.

A well-constructed hedge fund portfolio containing a select group of high-conviction strategies should enable plan sponsors to enjoy the risk/return benefits that hedge funds offer without significantly compromising overall portfolio liquidity. The challenges notwithstanding, an allocation to low-beta/high-alpha hedge funds can play a powerful role in enhancing a plan’s risk-adjusted returns and should be emphasized in the context of holistic pension risk management.

Conclusion

While plan sponsors should regularly review all four levers governing their pension strategy, they should pay extra attention to the growth lever at this point in the cycle. High valuations, lower expected returns, and equity market volatility also suggest that plan sponsors stand to benefit from re-evaluating their growth assets and ensuring they align with their objectives. In doing so, plan sponsors should consider the full spectrum of growth strategies, evaluate the potential for active manager value-add, and engage the appropriate resources to construct portfolios tailored to their specific needs.

Although timely, setting the return generation lever is not a one-time exercise. While maintaining a long-term view, plan sponsors must re-evaluate and recalibrate portfolios to ever-changing market conditions, plan circumstances, and sponsor-specific dynamics. For all plans, but particularly for those progressing along a de-risking glidepath, return generation goals, liquidity needs, and funded status volatility tolerance will evolve over time, necessitating changes to the size and composition of the growth portfolio. A comprehensive and nuanced view of the returns lever is critical to plan sponsor success.

Alex Pekker, Senior Investment Director

Barjdeep Kaur, Investment Director

Alex Sawabini, Senior Investment Associate

Performance Disclosure

The CA Nondiscretionary Portfolio Management Hedge Fund Composite includes 396 hedge fund program returns for the Cambridge Associate Group’s hedge fund clients who receive(d) hedge fund performance reports as of March 31, 2018. Returns shown are net of manager fees but gross of CA fees. At the inception of the composite, CA had two hedge fund clients in the sample. Clients are added to the sample over time based on their nondiscretionary investment management contract start date and are included for those periods during which they are nondiscretionary portfolio management clients. Annualized mean returns are calculated based on a monthly asset–weighted client composite return. This publication contains hypothetical performance. Hypothetical performance results have many inherent limitations and are used for illustrative purposes only.

This publication is provided for informational purposes only. The information does not represent investment advice or recommendations, nor does it constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities. Any references to specific investments are for illustrative purposes only. The information herein does not constitute a personal recommendation or take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situations or needs of individual clients. Information in this report or on which the information is based may be based on publicly available data. CA considers such data reliable but does not represent it as accurate, complete or independently verified, and it should not be relied on as such. Nothing contained in this report should be construed as the provision of tax, accounting, or legal advice.

Past performance is not indicative of future performance. Broad-based securities indexes are unmanaged and are not subject to fees and expenses typically associated with managed accounts or investment funds. Investments cannot be made directly in an index. Any information or opinions provided in this publication are as of the date of the publication, and CA is under no obligation to update the information or communicate that any updates have been made. Information contained herein may have been provided by third parties, including investment firms providing information on returns and assets under management, and may not have been independently verified.

Figure Notes

The Traditional Portfolio is made up of 60% MSCI All Country World Index (Net) and 40% Bloomberg Barclays Long-Term Government/Credit Index. The Traditional + HF Portfolio is made up of 40% MSCI All Country World Index (Net), 20% CA Nondiscretionary Portfolio Management Hedge Fund Composite, and 40% Bloomberg Barclays Long-Term Government/Credit Index. All portfolios are rebalanced monthly and do not include any contributions or benefit payments. The Bloomberg Barclays US Long Credit return is used as a proxy for the change in liability. MSCI ACWI returns use returns gross of dividend taxes prior to 2001, and returns net of dividend taxes thereafter. Returns are in USD terms.

Index Disclosures

Bloomberg Barclays Long-Term Government/Credit Index

The Bloomberg Barclays Long-Term Government/Credit Index is an unmanaged index of US government and investment-grade credit securities with a maturity of ten years or more.

Bloomberg Barclays US Long Credit

The Bloomberg Barclays US Long Credit Index represents long-term corporate bonds. It measures the performance of the long-term sector of the United States investment-bond market, which, as defined by the Long Credit Index, includes investment-grade corporate debt and sovereign, supranational, local-authority and non-US agency bonds that are dollar denominated and have a remaining maturity of greater than or equal to ten years.

HFRI Fund of Funds Composite Index

The HFRI Fund of Funds Composite Index is equal-weighted and consists of over 800 constituent hedge funds, including both domestic and offshore funds.

MSCI All Country World Index

The MSCI ACWI is a free float–adjusted, market capitalization–weighted index designed to measure the equity market performance of developed and emerging markets. The MSCI ACWI consists of 46 country indexes comprising 23 developed and 24 emerging markets country indexes. The developed markets country indexes included are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The emerging markets country indexes included are: Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Czech Republic, Egypt, Greece, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Pakistan, Peru, the Philippines, Poland, Qatar, Russia, South Africa, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, and United Arab Emirates.

MSCI Emerging Markets Index

The MSCI Emerging Markets Index represents a free float–adjusted market capitalization index that is designed to measure equity market performance of emerging markets. As of October 2016, the MSCI Emerging Markets Index includes 24 emerging markets country indexes: Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Czech Republic, Egypt, Greece, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Pakistan, Peru, the Philippines, Poland, Qatar, Russia, South Africa, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, and United Arab Emirates.

Footnotes

- Because alternative credit, and particularly private credit, is not as highly correlated to high-quality corporate bonds and liability discount rates as Treasuries and investment-grade credit, it may be considered part of the growth portfolio. However, given their cash flow–generative properties, fixed income–like characteristics, and generally lower expected returns compared to common growth assets, we include these asset classes in the liability-hedging portfolio in this publication.

- CA’s modified Public Market Equivalent (mPME) replicates private investment performance under public market conditions. The public index’s shares are purchased and sold according to the private fund cash flow schedule, with distributions calculated in the same proportion as the private fund, and mPME NAV is a function of mPME cash flows and public index returns.

- The term “low-beta/high-alpha” can take on multiple meanings depending on the nature of the plan and its risk tolerance, but it generally means that the strategy has a beta of significantly less than 1 (and perhaps as low as 0) to the equity markets and positive alpha relative to the beta-adjusted equity markets.