Endowment Governance Part 2 – Building the Team

Investment committee members have an opportunity to contribute to the financial health of an institution they care about, become a productive member of a team of volunteers and professionals who also care about the institution’s success, and learn a lot along the way. Being on a team can be very rewarding—and very exasperating. Investment committees are no different.

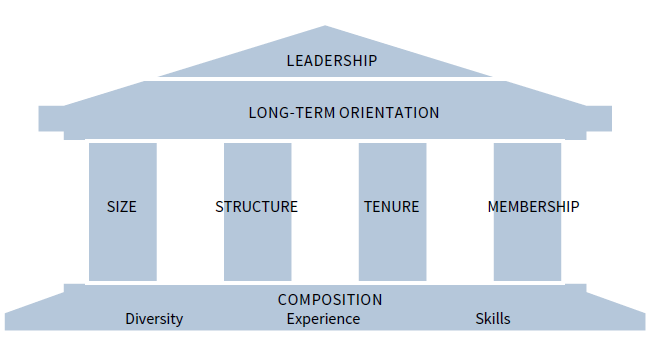

There is an art and a science to building an effective investment committee. The most effective investment committees comprise members with complementary skills and perspectives, an understanding of the long-term nature of an institutional portfolio, and an affinity for the organization. Different perspectives and institutional investment experiences are important. A long-term view that is aligned with the perpetual portfolio is essential. This long-term orientation unifies the committee members and governs their work. The committee’s work should be supported by membership, structure, size, and tenures that foster information flow, new ideas, and long-range stability (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 IDEAL INVESTMENT COMMITTEE COMPOSITION

Composition

Diversity. As much as possible, the composition of an investment committee should be diverse and reflect both the composition of the institution it represents and that of the world with which that institution interacts. Ideally, a committee should consist of people who bring different backgrounds and perspectives to the table and who are comfortable debating each other in a friendly and constructive way without seeking to impose their views on everyone else. If an investment committee consists of very similar people with similar backgrounds and experience, they are likely to think along very similar lines, and unhealthy results may ensue. For example, the conventional wisdom prevalent among this group of like-minded individuals may never be challenged, resulting in a kind of group-think ill-suited to the dynamic nature of investment management today. Debate is an important element of good governance, so the composition of the committee should avoid a dynamic where each member of the group identifies with the others, and everyone finds it difficult to challenge and disagree with another member’s ideas.

Diversity can be defined and sought in many ways. It might encompass ethnicity, race, gender, age, professional background, education, residence, and a host of experiences and choices. As Scott Page explains in The Diversity Bonus,

The best team will not consist of the ‘best’ individuals. It consists of diverse thinkers… And not in arbitrarily diverse way. Effective diverse teams are built with forethought.

Page’s research shows that when diversity of thought is joined with unifying principles, a team can achieve better outcomes when making complex decisions. 1

Experience. The type of investment experience suitable for an endowment is institutional investment experience, not personal or retail investment experience. The advisability of having committee members with institutional experience and perspective relates not only to the portfolio strategy (including asset allocation), but also to the very mission of the portfolio. Institutional and individual portfolios have very different risk profiles and demands. The distinction is not only between taxable versus tax-exempt investing, but also between the long-term mission of an endowment portfolio, which is intended to exist in perpetuity with investment performance and endowment distributions consistent with inter-generational equity and donor stipulations over a “perpetual” time horizon.

How important is professional investment experience? Though frequently sought after it is often best not to be composed entirely of investment professionals. Sometimes the members who are less familiar with investments can ask important questions and add an important perspective to the debate.

Membership. Most investment committee members should be members of the Board of Trustees, but in many cases the trustees can be augmented by non-trustees who have an affinity for the institution and bring sought-after skills to the committee. As the institution considers future membership, the field should be open to seek diverse perspectives that can contribute to debate and effective decision making. Non-trustee membership may be a proving ground for full trustee membership, so the process should also consider a member’s contributions to institutional culture.

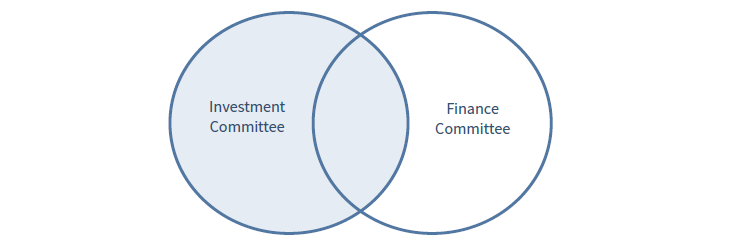

Structure. The investment committee should be separate from the finance committee (although it may be designated as a subcommittee of the finance committee, if necessary). However, these two committees should have at least one member in common to ensure that the left hand knows what the right hand is thinking and doing (Figure 2).

Overlapping membership and the presence of the institution’s CFO or COO at investment committee meetings can ensure adequate communication at the Board level between investments and finance so that portfolio construction will take into account any budget and finance considerations that may constrain investment decisions. It is also aided by certain kinds of models that permit the analysis of the impact of portfolio decisions on the institution’s “bottom line.” Increasingly, investment and development committee overlap forges an important link to the enterprise, and long-term goals for the endowment.

Size. Most endowed institutions not only succeed admirably in attracting highly qualified and willing volunteers to serve on the investment committee, but they may in fact wrestle with the problem of too many candidates. And this is a problem, since the inherent difficulties of decision-by-committee compound exponentially with increased membership.

We would not quite agree with the chair who declared that his investment committee should always have an odd number of members—and that three was too many—but to be consistent with best practice, an investment committee should have no more than eight voting members, including ex officio members, if any. In addition, non-voting “spectators” should not be permitted to attend meetings unless they are contributing to the agenda, otherwise their presence can be a distraction from the business at hand.

Tenure. There are prominent examples of endowment funds benefiting from the decades-long service of dedicated, highly qualified, deeply experienced investment committee members, but there are just as many examples of lethargy endured by institutions that have failed to inject new blood into their committees. Time limits provide for “fresh perspectives” to be added continuously to an investment committee and can help the group avoid certain dynamics that can occur with longstanding groups, such as committee over-agreement with one another (“group-think” noted above), stale agendas, and long-time domineering voices, if any. Even more compelling is that the investment environment and capital markets undergo constant change, and it is wise to add new talent to help address the new developments. New members should be met with an orientation program that begins with a fundamental understanding of the portfolio’s role in supporting the mission, investment policy, and process.

As a general rule, the tenure of investment committee members should be long enough to ensure consistency—and for members to be accountable for the results of their decisions—but explicitly limited and staggered to ensure continuity. Best practice suggests no more than ten years of continuous service on an investment committee by any given member. Since neither the institution nor the new committee member can ever be quite sure whether their relationship will prove satisfactory, a relatively short-term appointment lasting three or four years seems sensible. This can then be renewable once or even twice after which time a committee member rotates off as a matter of routine, giving the Board the opportunity to retain the services of excellent committee members. Committees that wish to have the ability to keep a particularly talented member who is approaching ten years will selectively allow reappointment of a committee member after at least one year of rotation off the committee.

Terms are often useful recruiting tools, because talented people may want to contribute to the process but cannot commit to serve for an indefinite period of time. Terms that limit the length of service to encourage new participation must be accompanied by strong succession planning. This involves developing a healthy pipeline that enables an organization to recruit incoming talent. The chair and other Board members play a key role in this ongoing cycle.

Mindset. The best investment committee members are open-minded, quick to acknowledge what they do not know and eager to remedy the deficiency, good at identifying the right questions to ask, and accustomed to making decisions. In contrast, the very worst candidates are often overconfident individuals who are impatient with committee consensus-building and implicitly believe that their lack of knowledge (of institutional investing in general or of specific asset classes) presents no impediment to their dictating how the portfolio should be managed. The investment world is different from most other worlds: in other professions, doing more of what has worked is usually the route to success—in other words, past performance is generally predictive of future success because the information necessary to make successful decisions is readily available to those trained in that profession. In certain key respects, however, this is simply not the case in the investment world—certainly not over a time horizon of several years—and committee members who cannot grasp this fundamental fact often end up chasing last year’s winners, inflicting considerable damage on the portfolio as a result.

Anyone who joins the committee should understand that they are being asked to take a long-term view and steward the investment policy statement (IPS). While changes may be in order, there should be a bias toward continuity and stability in the program; members should be in a philosophical alignment with the investment program, so long-term objectives are not usurped by membership changes or short-term impatience.

Leadership

Good chairs are at once very good people managers in the sense that they are caring, observant, and direct, while also being strategic. A good chair appreciates the mission of the organization and the work of other committees. She or he forms partnerships, shows humility, and is intellectually curious. The chair leads today and is always recruiting for the future.

Best practices for committee composition, process, and policy all come together under the chair’s leadership. The chair is the linchpin of the investment committee, working closely with executive staff, advisors, and committee members, cultivating relationships and trust with each. The role of chair does not entail directing strategy or imply that the leader has a greater say than others in what decisions are made. The chair enables discussion and brings all views out into the open. When a strong leader is at the helm each member is heard and has opportunity to engage in the process. Healthy relationships and trust are paramount to robust discussion and effective decision-making. Collaboration and strong communication also provide conditions for checks and balances.

Effective chairs are not necessarily those with the most investment expertise. They understand institutional investing, but they also bring management skills to the position. Good chairs are good people managers. They are caring, direct, and take time to get to know their membership, so that each member can contribute his or her talents to the process. Successful leadership yields collegiality, respect, engaged members, informed decisions, and regular attendance.

Effective chairs also understand the organization that the investment portfolio is supporting. As a leader, the chair needs to integrate the investment program with the mission, goals, and circumstances of the entire organization. As one chair summarized, “You can’t just say, ‘I’m doing the investment committee, and someone else is doing finance, etc.’ You have to appreciate what the organization does—its mission and history and what other groups are doing. You have to have perspective.” When the chair can promote the alignment of the investment work with the organizational purpose, investment decisions are tied to the institutional identity, and the committee is connected to the importance of the work. They are also in tune with the enterprise risk and liquidity needs.

Debate and Divergent Opinions. Unlike most other trustee committee meetings, which usually end with unanimous approval of the course of action recommended by the institution, investment committee meetings should ring with divergent opinions forcefully expressed. The chair must cultivate the group’s ability to have difficult conversations in the context of their shared purpose. Thorough debate and diverse perspectives are balanced by focusing the committee’s attention on the long-term goals, the guidance of investment policy, institutional values, history, and purpose. The chair’s job is to steer a sometimes difficult course between keeping the discussion on track and ensuring that all committee members have their say. The chair should also assume responsibility for following up with absent committee members, both to brief them on the meeting and to determine whether they have any objections to the decisions made.

Engagement. Good chairs engage committee members outside of meetings, not in a way that overwhelms the member with additional commitments, but in a way that enhances his or her work. Opportunities to engage with the chair and other members can establish important working and personal relationships and provide a network. The effective chair is nurturing individual relationships and setting the tone of the group.

Periodically the committee should have a mechanism to evaluate its effectiveness and be reflective. This may come via individual conversations, or a more formal self-evaluation process. The emphasis of the exercise should be on the group and whether the committee continues to work effectively together and adhere to its core principles. The exercise should produce validation or productive recommendations for improvement regarding the structure, process, and policies. The chair would then take actions to introduce improvement and remedy any deficiencies.

Ultimately, a well-constructed investment committee is successfully joined together with the secret sauce: committee culture. Members come together with complementary contributions to the group, a shared understanding of their role in the endowment’s long- term goals, and a spirit of debate and respect that makes the work enjoyable. The successful result is a committee working with conviction and in an institutionally specific way.

Great committees know who they are, they understand their institution and its goals, and they are not over chasing the trends of the market. Members respect each other even if they disagree. They are aware of the importance of their work, and they work at the right level. With ongoing succession preparation, the culture and conviction of the committee continues even as the individual participants change. ■

READ THE ENDOWMENT GOVERNANCE SERIES

The “secret sauce” to long-term investment success is, in most cases, the governance that guides and oversees the investment program. Read part 1 of the series for details on the job description and part 3 for tips on process and engagement.

Footnotes

Tracy Filosa - Tracy is a Managing Director and Head of CA Institute.

About Cambridge Associates

Cambridge Associates is a global investment firm with 50+ years of institutional investing experience. The firm aims to help pension plans, endowments & foundations, healthcare systems, and private clients achieve their investment goals and maximize their impact on the world. Cambridge Associates delivers a range of services, including outsourced CIO, non-discretionary portfolio management, staff extension and alternative asset class mandates. Contact us today.