As the economic cycle progresses, the next recession draws inexorably closer, bringing with it the next downturn in the credit cycle. Recognizing this, institutional investors are increasingly considering allocations to distressed debt managers. While lumping all distressed managers into one group is tempting, different managers have meaningfully different approaches that are not captured by considerations like geographical or vintage year diversification. Further, investors’ traditional way of thinking about distressed debt managers makes timing paramount. In this paper, we offer a new way to think about distressed investing that combines three complementary sub-strategies and encourages investors to allocate across the credit cycle.

The Probability Tree Approach

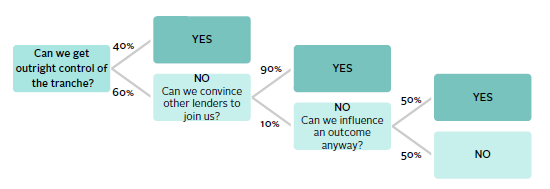

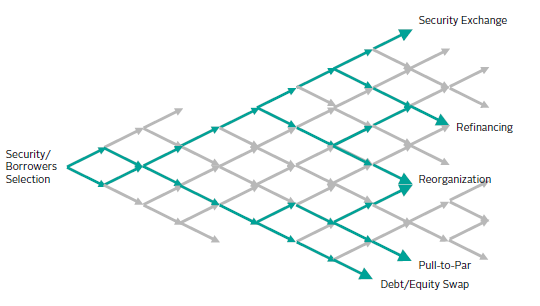

One way to consider differences among distressed managers is to use an old tool from option pricing: the probability tree. A probability tree can be used to price convertible bonds, options, or any other financial asset with a value that depends on a range of possible paths (i.e., path dependent assets). These paths usually refer to price changes and their attendant probabilities. The value of an asset priced in this way is the sum of the products of the outcomes and their attendant probabilities (discounted back to today at the appropriate rate and time).

Probability trees can also be used to chart other outcomes—the accumulation of a blocking position in a debt tranche, the accumulation of outright control of a debt tranche, the private equity owner’s commitment to fund an upcoming commitment, the forbearance (or not) by senior lender of its creditor rights, etc. Distressed debt investors face these and many other potential outcomes when purchasing distressed securities. The succession or concomitance of these outcomes can influence the ultimate value of a security, and hence the returns generated. For example, a distressed investor with the ultimate goal of owning a distressed borrower by accumulating a controlling position in a senior debt tranche to drive a favorable bankruptcy process may find these plans thwarted if it cannot accumulate a controlling interest. Without a controlling interest in a debt tranche, that investor may seek to build consensus with other holders in the tranche, persuading them to adopt its restructuring plan.

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Thinking of these outcomes as a path to realizing value permits the application of probabilities to them, creating a conceptual probability tree. This conceptual tree can begin with the first buy decision and end with ownership of post-reorganization securities. Final outcomes can also include liquidation, refinancings, or an exchange offering, each with different values and different returns. Points along the way can be reframed as decision nodes with questions such as:

- Can we accumulate a blocking position?

- Can we accumulate a control?

- Do we know the other holders, and if so, can we partner with those other holders?

- Will they work with us?

- Does the suite of documents permit the company to dispose of assets?

- Is the management team engaged and incented to address the situation?

- Are the lenders in other tranches cooperative?

- Do inter-creditor agreements offer other lenders rights to interfere with our plans?

- Is bankruptcy a real option?

- If bankrupticy is, is the presiding judge likely to be favorably disposed to it?

Each of these nodes would have two paths emanating down the tree: “Yes,” with a probability of x, and “No,” with a probability of 1–x.

Some of these questions can be identified (but not answered) a priori, while others arise “on the fly.” For example: Will the court permit J. Crew to shift intellectual property to another subsidiary? Will Richard Davis’s final report to the court conclude there was fraudulent conveyance in the Caesar’s Casino bankruptcy? If so, will the amount exceed $3 billion? The most skilled managers can see the a priori probability tree and drive toward a desired path with their finance, legal, and interpersonal skills, reacting accurately and prudently to new decision nodes that arise unexpectedly.

Running Through the Trees

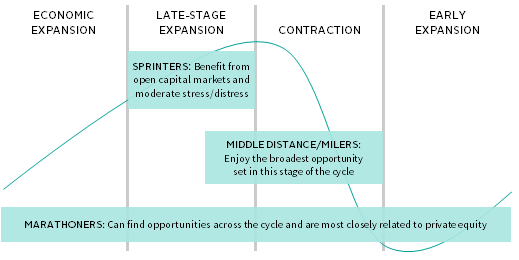

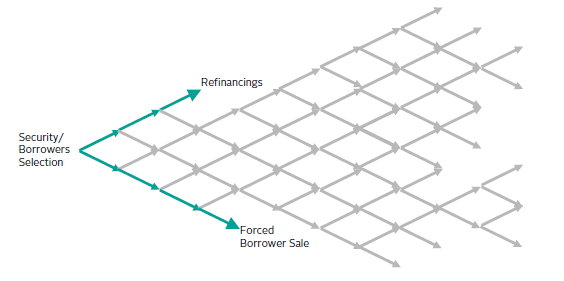

By viewing distressed investing as a path along a complex probability tree, investors can differentiate among managers based on their appetite for path length and complexity. Some managers have a limited appetite for length and complexity and seek opportunities that offer quick exits, mainly through refinancing at par. Others are happy to ride the probability tree to ownership of post-reorganization equity. The vast majority fall somewhere in between.

For ease of description, we will refer to those with limited appetite for length and complexity as “sprinters,” those willing to ride to the very end as “marathoners,” and those in between as “milers” or “middle distance” managers. Grouping managers allows investors to determine whether their skills match their strategy in much the same way coaches and trainers can determine whether an athlete has the build, stamina, and pace to sprint, run a mile, or complete a marathon. Moreover, differentiating among managers facilitates portfolio construction in the same manner that identifying skills helps a trainer build a track and field team.

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Sprinters

Sprinters seek a quick path to exit. They are not interested in engaging in protracted litigation, enforcement of creditor rights, consensus building around other lenders, or company engagement. They do not care to own conversion securities and are even more averse to assuming ownership of a borrower. Instead, they wish to exit through a refinancing, or a “pull-to-par” adequate to drive returns. While sprinters may benefit from broader market (“beta”) forces, they can also find investments in buoyant markets where borrowers suffer from temporary financial difficulties.

One way to confirm that a manager is a sprinter is to examine the percentage of its portfolio that has been refinanced at par (whether triggered by the sale of the borrower or not). If the majority of a manager’s investments are refinanced at par, that manager is almost certainly a sprinter. Similarly, their hold periods will be relatively short, with sales into the market as the exit in the case of more liquid strategies. While this strategy sounds appealing, it is difficult to execute because the opportunities are not easily sourced on the private side and in more liquid strategies, the manager may carry excessive market risk. Distressed situations are often highly complex, involving numerous stakeholders with frequently opposing views. Sprinters, therefore, need either an edge or a differentiated strategy to get out fast. An institutional investor’s due diligence should focus closely on the “edge” that enables a sprinter to succeed.

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Marathoners

Marathoners are in for the long run and have the appetite to see restructuring through to the conversion of their debt security into post-reorganization equity ownership. Distressed-for-control managers tend to be marathoners. They recognize that the extended probability tree is a means to an end: control of the borrower to effectuate a turnaround of a struggling company into a profitable gem of a business. Marathoners will advertise their intentions to institutional investors and will showcase private equity–like management capabilities deployable at assumption of control.

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

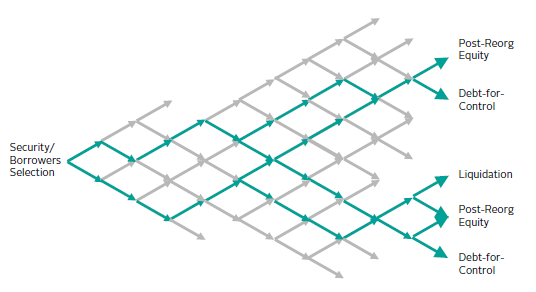

Middle Distance/Milers

Milers represent the largest category of distressed debt investor. They exhibit not just powerful financial analysis capabilities, but also considerable legal prowess. They embrace enforcement of creditors’ rights as a real option and know how to influence, persuade, threaten, and cajole stakeholders. Like the middle distance athletes that can run an 800 meter race or as far as 5,000 meters, these managers can execute a quick exit or manage an extended process all the way through bankruptcy, as the circumstances dictate. Milers will have at least one former bankruptcy attorney on staff, and their portfolios will have a large number of small “toehold” investments—tentative forays into new investments to identify the contours of the specific probability tree. They will talk about “litigation strategy” and embrace complexity. Because milers are the most numerous, institutional investors can expect to see some overlap in the investments of different managers. But the best managers will lead processes, much like how the best milers set the pace that others follow.

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

The Asset/Liability Remix

Within these groupings, distressed managers can be further described based on their focus on either assets or liabilities.

While they have vastly different appetites for path length and complexity, sprinters and marathoners share a focus on the asset side of a borrower’s balance sheet. Naturally, they must be sophisticated readers of credit agreements and bond indentures, but they are mostly focused on enterprise value. Sprinters need enterprise value to be readily recognizable so that their investments can be refinanced at par in a relatively short period of time. They cannot afford legal entanglements and protracted court battles. Marathoners, in contrast, need fundamentally sound businesses that can withstand the trauma of a restructuring—businesses that offer sound foundations on which to rebuild once the dust settles. The paths of these managers differ in length and complexity, but ultimately both sprinters and marathoners make the same bet on the resilience of the borrower’s underlying enterprise value.

Milers focus more on the liabilities. They must be aware of assets and enterprise value as well, but they thrive in the complexity of byzantine legal structures and overlapping documentation. Milers often underwrite numerous exits, including outright ownership of a borrower, sale to another creditor in search of a controlling stake, liquidation, a favorable court ruling in bankruptcy proceedings, or a recovery in underlying bond or loan value. Naturally, not every investment has all of these paths to exit, but building a portfolio of investments with one, some, or all of these possible exits require a greater focus on creditor rights.

Allocating Through the Cycle

Sprinters, milers, and marathoners prosecute these different strategies in pursuit of the same target returns of more than 12%. Investing across different types of distressed managers allows investors to allocate capital in a manner that diversifies strategy and offers opportunities across the credit cycle.

For example, allocating to marathoners, who wish to own equity, might be wiser when capital markets are less accommodative and access to capital is more constrained, two phenomena that make it difficult for struggling companies to ignore financial woes. Market participants currently cite today’s capital markets as providing ample liquidity to even marginal borrowers. Nevertheless, the best marathoners can find good investments even under these conditions.

Early to late in an expansion cycle, sprinters may be the better choice as they seek to exit investments quickly, when refinancing opportunities are more abundant. They are therefore less likely to be caught holding deteriorating assets when the cycle turns. And today’s capital markets are wide open, accommodating the refinancings that frequently support sprinters’ exits. However, for how long will that continue?

Middle distance runners are also not without risks. While they may map out certain paths along the probability tree, markets can change quickly, causing them to abandon those paths in favor of new ones.

This differentiation does not mean to suggest that all sprint strategies will outperform all marathon strategies early in the cycle or, as the cycle progresses, every middle distance manager will outperform every sprint manager. Rather, identifying and categorizing strategies as sprinters, milers, or marathoners helps investors differentiate, analyze, and set expectations for each manager.

Seeing the Forest Through the Trees

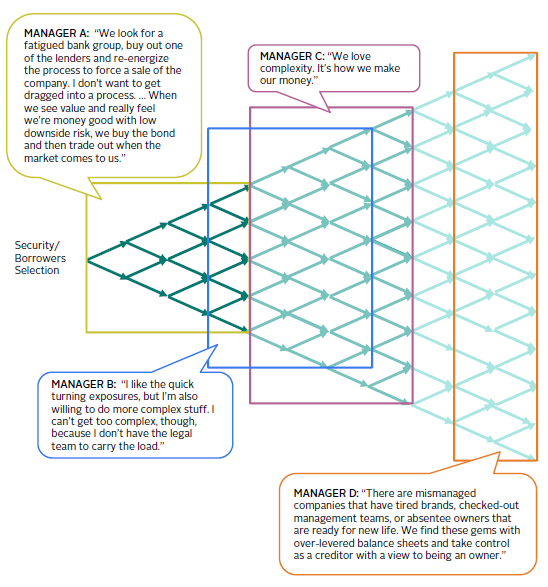

This framework offers a way to orient discussions with managers. In our experience, asking a distressed manager to identify its strategy within this context has led to more efficient conversations. Using our probability tree framework, Figure 6 depicts how four managers we talked to identified themselves.

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

Referencing this framework makes it easier for managers to define the risks they are willing to accept and level of work they are able to perform. Naturally, self-identification is the first step and it creates a launching point for further due diligence and portfolio construction and monitoring. For example, due diligence might focus on a self-defined middle distance manager’s legal acumen or a marathoner’s operating capabilities. Similarly, this framework offers guiderails for monitoring style drift. We have found that the framework offers a straightforward map to guide relationships with managers.

Conclusion

Investors can allocate to a distressed portfolio entering into a credit cycle by layering in managers expert in sprint strategies, followed by middle distance runners, and select marathoners throughout. The key is that these strategies should be viewed as a portfolio. When the cycle turns, sprinters will struggle to find exits and their hold periods will extend. But their struggle will bode well for middle distance runners, who should see their opportunity set expand contemporaneously. Identifying distressed managers as sprinters, milers, or marathoners can help investors to better differentiate and more constructively allocate through the cycle.

Tod Trabocco, Managing Director