Ready, Steady, Co-Invest

Co-investments are one of only a handful of control levers within a limited partner’s (LP) toolbox, and we encourage all private market investors, regardless of size, to consciously consider implementing a co-investment program. In 2015, we provided an introduction to the multitude of benefits co-investments may add to a private investment program. Since then, Cambridge Associates’ Co-Investment practice has sourced more than 1,000 investment opportunities, totaling nearly $90 billion of capital requirement. We have worked extensively with clients to successfully integrate co-investments into many private investment portfolios. Drawing on our collective experience, this follow-up piece highlights an actionable co-investment framework for investors.

Make a Conscious Decision

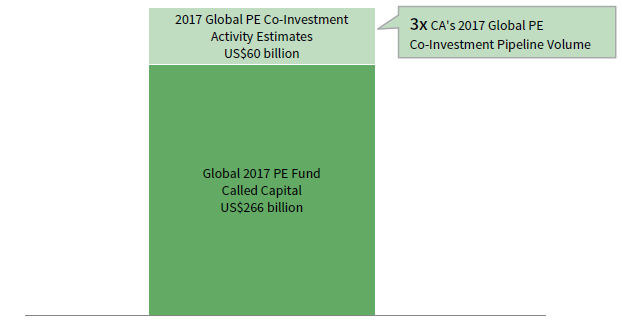

The co-investment market’s size and diversity are key reasons why we think investors should make a conscious decision about the opportunity set, rather than passively overlooking it. While the co-investment market is opaque, even conservative estimates suggest deal flow is substantial. In 2017, we saw roughly $20 billion of global private equity co-investment opportunities. Assuming that we saw a third of the market (because, let’s be honest, no one sees the entire market), 2017 global private equity co-investment deal flow would be about $60 billion. According to Cambridge Associates data, global private equity firms called roughly $266 billion in capital from LPs in 2017, implying that co-investment activity composed approximately 20% of overall market activity (Figure 1)! Given the size of this space, we encourage investors to—at the very least—retain the option to pursue co-investments.

THE CO-INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY

FIGURE 1 GLOBAL CO-INVESTMENT MARKET ESTIMATE

As of December 31, 2017

Sources: Cambridge Associates LLC Private Investment Database.

Note: Co-investment activity is based on Cambridge Associates co-investment deal flow.

Do the Math

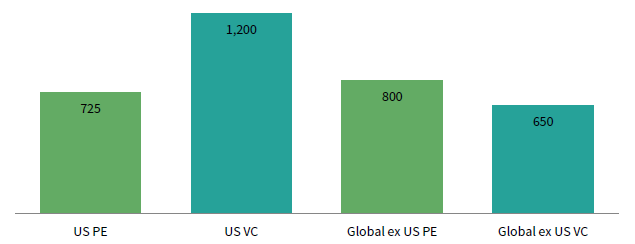

The primary goal of any successful private investment program is to serve as a meaningful return driver to the total portfolio; the objective for co-investing is no different. Co-investing offers potential return enhancement through fee reduction, J-curve mitigation, and the opportunity to tactically increase exposure to high-quality investments. Investors should not underestimate the fee-reduction benefits, as the average difference between gross and net returns for a US private equity fund is 725 basis points(bps) (Figure 2). Consequently, even a modest allocation to co-investing can improve the return profile of a private investment program, as most co-investment opportunities are offered to existing LPs with no (or reduced) management fee or carried interest. This is before incorporating the effects of a shortened J-curve due to immediate capital deployment when co-investing. Further, we advocate that investors be tactical, not universal, in pursuit of co-investing. While LPs could commit to every co-investment they are shown (to blend down the program’s overall cost basis), why should an investor abdicate the ability to exercise discretion over when and where to invest? As mentioned, co-investing is one of few control levers available to private market investors, in addition to fund commitments and secondary transactions, and being properly equipped to co-invest may amplify overall program returns.

FIGURE 2 AVERAGE GROSS TO NET SPREAD

Basis Points (bps)

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC Private Investments Database.

Notes: Calculated as the spread between gross company-level returns and net fund-level returns using 622 US private equity

funds, 1,043 US venture capital funds, 443 global ex US private equity funds, and 146 global ex US venture capital funds. The

sample excludes funds that do not provide company-level data.

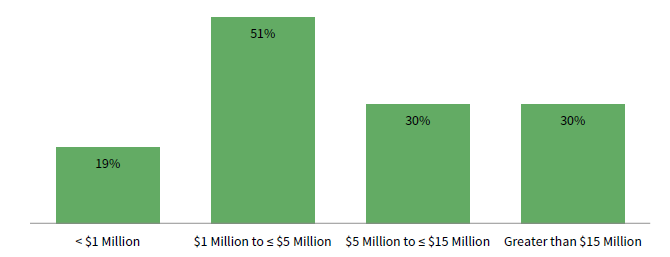

Everyone Can Participate

Contrary to popular opinion, co-investments are available in all sizes and strategies and consequently may be implemented by a variety of investors (Figure 3). Sizing an individual co-investment is not a remarkably different process than sizing a fund commitment. For instance, investors should approach allocation decisions with similar factors in mind and consider the risk/return tolerance of the overall program. One way an investor may construct a co-investment program is similar to how a general partner (GP) typically structures a fund—follow predetermined exposure limits and invest over a multi-year time horizon. These exposure limits may incorporate size, strategy, sector, geography, and risk/return profiles, among other specific factors. As we address later in this piece, investors must also consider the resource requirements to evaluate, execute, and monitor the co-investment program.

FIGURE 3 PERCENTAGE OF CA COMPLETED CO-INVESTMENTS BY INVESTOR AMOUNTS

As of December 31, 2018 • Percentage (%)

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC Private Investments Database.

Notes: Represents percentage of completed co-investments that included an individual client investment within the given size ranges.

Multiple investment sizes can be included in a given co-investment, which is why the four groups may not total to 100%.

Worth the Hassle?

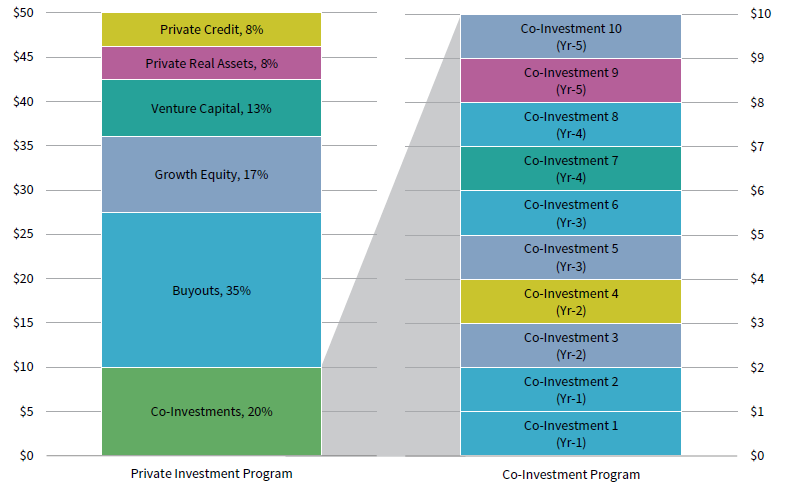

Let’s explore a representative portfolio construction example. Consider an investor with a $250 million portfolio that has a 20% allocation target ($50 million) to private investments (private equity, growth equity, venture capital, real assets, etc.). This program’s average fund commitment typically ranges from $3 million to $5 million across 10 to 15 active funds. As a rule of thumb, we recommend that investors size each co-investment at 25% to 30% of their typical fund commitment (by dollar), or in this example, $750,000 to $1.5 million per deal. Going back to our GP fund model, we suggest that investors build a diversified portfolio of ten co-investments across a five-year period. At maturity, this program’s co-investment exposure would range from $7.5 million to $15 million, representing 15% to 30% of the PI portfolio and 3% to 6% of the total program (Figure 4). To maintain constant exposure, the investor would need to execute between one and two co-investments per year, which we believe is a reasonable pace given that we saw over 450 co-investment opportunities in 2018 alone. Tying this back to our return objective (and assuming these co-investments are executed on a 0% management fee, 0% carried interest basis), a private investment program with 20% exposure to co-investment could capture 100 bps in excess return, just from overall fee savings (Figure 5).

FIGURE 4 REPRESENTATIVE PRIVATE INVESTMENT PORTFOLIO – $50 MILLION

For Illustrative Purposes Only • US$ Millions

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC.

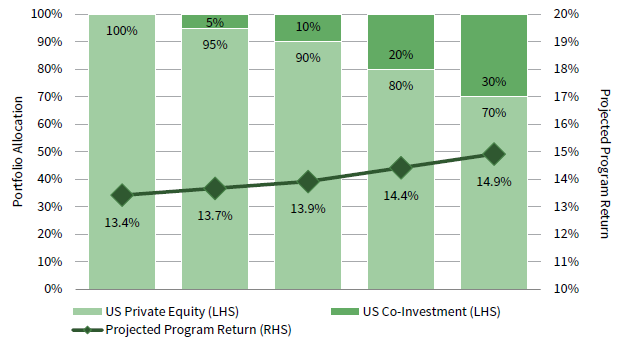

FIGURE 5 PRIVATE EQUITY PORTFOLIO RETURNS WITH CO-INVESTMENT ALLOCATION

As of September 30, 2018 • For Illustrative Purposes Only

Source: Cambridge Associates LLC Private Investments Benchmark Index.

Notes: To calculate the weighted projected program return, the 25-year periodic return for US private equity through third quarter 2018

was used, equal to a 13.4% net IRR, and co-investment returns were projected to be 500 bps higher. Weighted portfolio returns are

calculated by applying the strategy weights to long-term returns.

Be Prepared

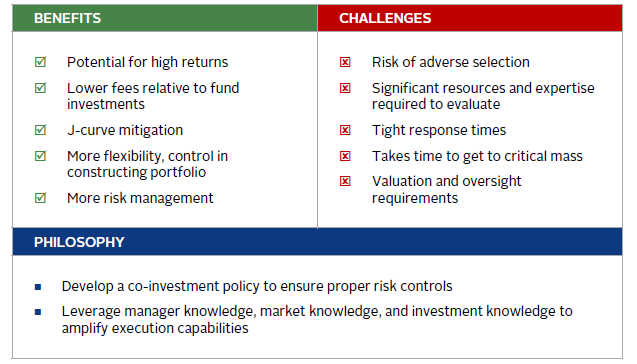

Clear objectives and parameters are critical to a co-investment program’s success. Co-investing is not fund investing; it is typically a decision to deploy capital into a single security or asset. Consequently, the range of outcomes for individual co-investments will be wider than for fund investments, which benefit from the diversification of multiple underlying portfolio companies. With this in mind, determining program objectives and their priority will help serve as a guide toward success. Failing to do so at the onset creates the opportunity for missteps that could restrict the co-investment program’s potential to be impactful. Objectives may include: return enhancement, pure cost reduction, social and environmental impact, building tactical exposure to specific sectors of interest, strengthening core GP relationships, and exploring new GP relationships. Alongside program objectives, investors need to define success and how to measure it because the program will likely take several years to build. As the program matures, investors should revisit and refine their objectives and success criteria so that the program stays on course.

Once goals are established, investors need to determine the best approach to accomplish them. As discussed earlier, we do not advocate for a passive “do every co-investment” approach. Why? Doing every co-investment might reduce the program’s overall cost of access, but it limits the opportunity to invest tactically and opens the door to adverse selection risk. Instead, investors should deploy capital in opportunities that have the greatest potential to add value relative to program objectives.

An active strategy has further potential to capture upside and mitigate downside risk, but how active should a co-investor be? There are degrees and LPs should consider the resources required to implement such a strategy. If LPs intend to evaluate the manager’s underwriting, they probably should have dedicated investment professionals, with relevant direct or co-investment experience. While costly, active co-investors have the opportunity to put together a co-investment wish list and pro-actively source investments that meet program objectives. They may aggressively pursue high conviction GPs to both source high-quality investments and build stronger relationships that may lead to increased fund access. LPs may underwrite investment opportunities alongside the GP (accepting completion risk in the process) and also build theses around certain sectors and areas of interest. All in, active investors have more flexibility and opportunity to structure a co-investment program that meets their desired (and stated!) objectives. However, to do so successfully requires that co-investors are constantly out in the market and in front of these GPs. Not all LPs are positioned to do so.

Process is also key to successful implementation. Co-investment transactions can occur rapidly (from start to finish in as little as five business days). As we have learned from thousands of conversations with GPs, speed and certainty of close are often a sponsor’s top two criteria in finding co-investment partners. For an LP that is used to the cadence and flexibility of the primary fundraising cycle, adjusting to the co-investment pace may be challenging, particularly without well-defined objectives and processes. The most frustrating outcome for a GP is when an LP takes significant time and attention throughout the diligence process and backs out of the investment at the eleventh hour due to a simple process item that could have been addressed days (if not weeks) earlier. Given the current demand for co-investment opportunities, LPs must be careful not to alienate GPs (as the LP’s sources of deal flow) late in the diligence cycle. However, investors should not shy away from passing on a deal because of legitimate concerns that arise through new information introduced during due diligence.

Potential co-investors must also determine what information they need to monitor their program effectively, as investors will have different reporting requirements for their respective institutions. While the GP will typically provide monitoring, LPs may also negotiate direct information rights. LPs should regularly evaluate each individual company’s financial results and measure the performance of the overall co-investment program against stated expectations.

Be Mindful of Market Cycles

Co-investing is also a way to express an investor’s view of the current market environment. An individual co-investment is immediately deployed into the prevailing market conditions, influencing its ultimate performance. Investors can further express their view of market conditions through the types of co-investments pursued. Co-investments can generally be used to build exposure when the market environment is favorable, while tapering off when valuations are frothy. Market volatility should have an increased effect on an individual co-investment relative to fund investments that are diversified across numerous assets and deployed over a multi-year time period. Consequently, LPs should place a greater emphasis on considering near-term market volatility when co-investing, versus fund investing.

At a Minimum, Preserve the Option

At an estimate of nearly 20% of overall private equity activity, and potentially substantially more, co-investing is a material investment strategy practiced by institutional investors and family offices. As one of few control levers in a private investor’s arsenal, we believe that all private market investors should consciously consider whether it is in the best interest of their program and within their capabilities to implement a co-investment strategy. If LPs choose to pursue co-investment opportunities, they should do so thoughtfully, systematically, and with clearly defined objectives and processes. In the constant search for returns, investors that position themselves as an efficient and reliable co-investment partner may be able to capture meaningful value for their portfolio.

Andrea Auerbach, Managing Director

Rob Long, Senior Investment Associate

Scott Martin, Managing Director

Other contributors to this report include Caryn Slotsky, Ronny Chatterjee, and Jacob Gilfix.