VantagePoint: Asia Opportunities Amid Shifting Geopolitics – Part I

The shifting geopolitical realities between the United States and China have already impacted trade and investment flows. In this two-part series of VantagePoint, we review this reality and consider investment implications alongside those of other key factors—such as domestic structural developments, macroeconomic conditions, and valuations. In Part I, we focus on opportunities in China specifically, and in Part II, we discuss other Asian investment opportunities beyond China.

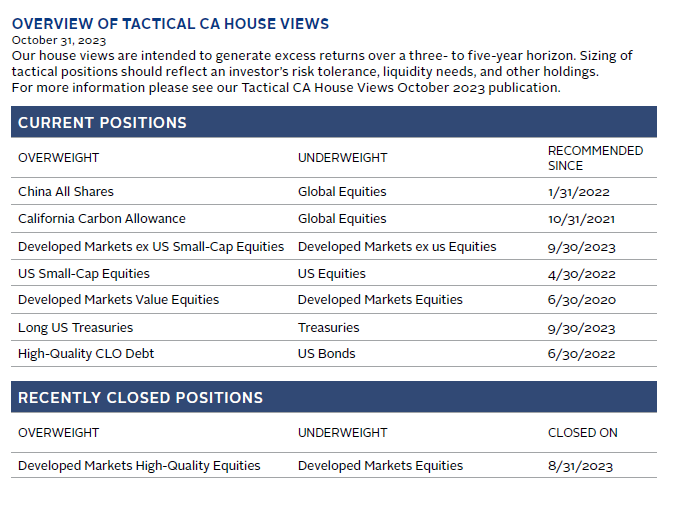

In sum, China remains an important destination for investor capital, while geopolitical realities are creating additional investment opportunities elsewhere in Asia. We recommend modest overweights to Chinese public equities relative to global equities, as cheap valuations compensate for the risks. We take a more cautious and selective approach toward venture capital (VC) due to longer-term risks, especially the uncertainty associated with US policies to discourage investment in China and restrict access to advanced technology. It will take time to see how regulations evolve and how managers adapt. The investment opportunity set may be limited or less profitable, particularly if the United States is successful in holding back technological developments. Indeed, VC managers have largely paused fundraising activity for US dollar funds driven by the uncertain outlook. We see promising macro developments across much of Asia, particularly in India, Japan, and Southeast Asia (also known as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations [ASEAN]). 1 That said, valuations keep us neutral on public equities in the former two markets, while implementation is challenging in ASEAN. In private markets, Indian VC and Japanese buyouts offer particular appeal.

The Shifting Landscape

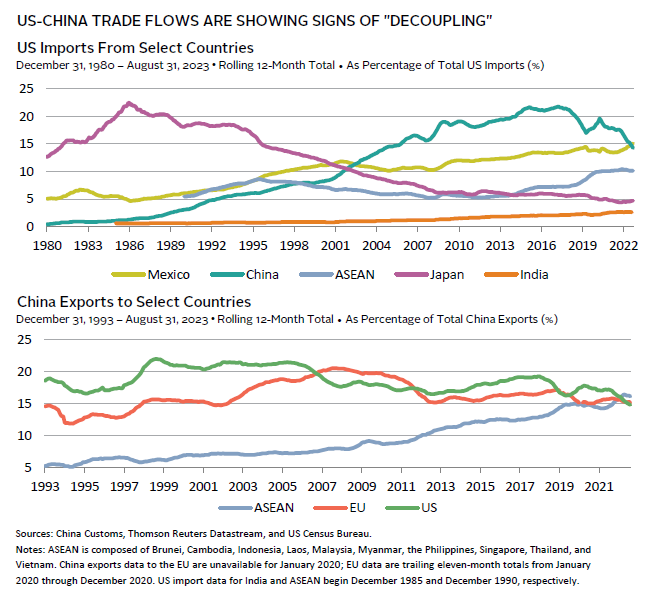

Tensions between the United States and China have further intensified over the past two years since we last discussed China in depth. Trade and investment “decoupling” is occurring faster than many may realize. For instance, the United States now imports more from Mexico than it does from China, and China’s share of total US imports has fallen to levels not seen since 2005. At the same time, China’s exports to ASEAN now exceed those to both the United States and Europe, while China’s exports to emerging economies exceed those to Europe, Japan, and the United States combined.

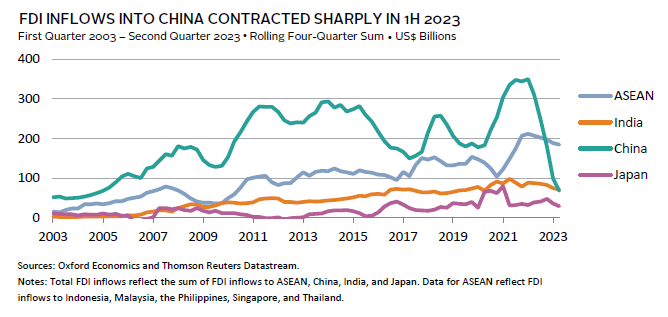

Foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows to China fell to $25 billion in first half 2023, down more than 80% from first half 2022 levels to a more than 20-year low. India is now attracting more FDI flow than China, while ASEAN now accounts for significantly more than China, India, and Japan combined. At the same time, US real investment in manufacturing construction has surged 70% since the end of 2019. While there have been other periods of falling FDI flows into China, none have occurred amid a backdrop of shifting trade patterns away from China. In other words, these shifts may be more structural than cyclical.

These shifts are especially remarkable, given China enjoyed a surge in exports and FDI during the pandemic as Chinese factories remained opened and supplied the world with much-needed goods. Concerns of overreliance on China as the workshop of the world and the supply-chain vulnerabilities this entails were reinforced by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, which intensified the West’s focus on geopolitical risks, particularly around Taiwan and supply chains in Asia.

The Geopolitical Realities

Policymakers, corporations, and investors are increasingly making trade flow and investment decisions through a geopolitical lens. The renewed focus on geopolitical risks in the West has occurred alongside a shift in political focus in China toward national security and self-sufficiency that began before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The growing assertiveness of US policy actions toward China (and hawkishness by politicians on both sides of the US political spectrum) has convinced Beijing that a new Cold War is underway, with the United States seeking to implement a modern-day “containment” strategy centered around technology and capital flows in an effort to slow China’s technological advancement. This is particularly highlighted by the sweeping 2022 restrictions on the sale of US-linked semiconductor technology to China and the recent 2023 executive order restricting US investment in China in the areas of advanced semiconductors, quantum computing, and artificial intelligence. While the United States insists the focus is “competition, not containment” and “de-risking, not decoupling,” the net effect is largely the same.

As a result, China’s political priorities remain to reduce its strategic vulnerabilities. Specifically, China is focused on reducing reliance on sea-borne imports of raw materials, which are vulnerable to foreign navy interdiction; reliance on US technology (especially semiconductors); and reliance on the US dollar financial system for trade and capital flows. For example, China’s refusal to abandon Russia as an ally is partly to secure reliable and cheap overland access to energy, just as China’s One Belt One Road 2 investments in central Asia, the Middle East, and Africa are done to secure natural resources from “friendly” governments. Indeed, China’s push to be a world leader in clean energy and electric vehicles is partly to reduce the need for energy imports (in addition to the environmental benefits).

The change in China’s political focus represents a major ideological shift relative to the last 40 years. Beijing has de-emphasized prioritization of economic development, placing primary emphasis on national security and self-sufficiency. Furthermore, the consolidation of power under President Xi Jinping means policies can be implemented even faster when directed from the top (such as the abrupt ending of zero-COVID policies last year). However, it also has removed many of the internal checks and balances on policy making that existed in the past.

At the same time, the United States and Europe have recognized their overreliance on China-centric supply chains and energy from Russia, prompting them to push for “friend-shoring” and even greater focus on renewable energy. While the Biden administration is seeking to improve communication channels with China to help stabilize acrimonious relations, the political desire to reduce exposure to China will not change regardless of the outcome of the US elections in 2024. Further reproachment is possible, but geopolitical dynamics are unlikely to change anytime soon, especially given the Israel-Hamas war could further strain US-China relations should Iran be drawn into the conflict.

What about war? Will the de facto Sino-US Cold War turn into an actual military conflict? While military conflict cannot be dismissed, the odds of an invasion of Taiwan seem low until China has reduced its above-mentioned strategic vulnerabilities and has achieved adequate levels of sufficiency. Whether China can meaningfully reduce these strategic vulnerabilities over the next ten years (the typical time horizon for private equity [PE] fund investments) remains to be seen, but until then turning the South China Sea into a war zone would damage China more than it would the West.

Nevertheless, elevated geopolitical risks and related shifting priorities require that investors think critically about how changing geopolitics may affect economic and corporate fundamentals rather than relying on the past 40 years as a guide to the future.

China: Crossing the River by Touching the Stones

What do the above dynamics mean for existing and future investments in China? While US technology restrictions are likely to slow China’s technological progress, it is unlikely to derail it, given the potential for domestic innovation and substitution. Indeed, it will simply force China to direct more resources toward self-sufficiency and improving domestic productivity, a key priority if China is to offset the headwinds from declining demographics. Thus, investment opportunities related to the sub-themes of rising consumption, advanced and automated manufacturing, climate tech, and healthcare (a theme that benefits from an aging population) will remain.

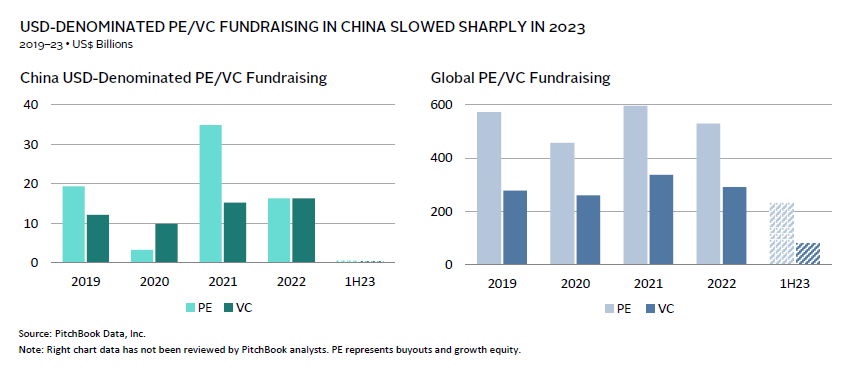

The question is whether US and European investors will pursue these opportunities, particularly via private equity and venture capital (PE/VC) investments. Over the first half of 2023, USD fundraising for China PE/VC funds was a miniscule $0.9 billion compared to $32.6 billion in all of 2022, let alone the $50.1 billion in 2021, according to PitchBook Data, Inc. While global VC fundraising has also slowed, the collapse in China fundraising is directly tied to geopolitical tensions, as investors await clarity on US investment restrictions on China. The recent Biden administration executive order was limited to only three technology sectors, but the rules have not been finalized and many practical questions remain about how the restrictions will be implemented. This means the current freeze in fundraising is unlikely to thaw soon as both investors (LPs) and managers (GPs) still need to assess the implications.

To the degree that the US executive order prohibits US-linked GPs and LPs 3 from investing in these sensitive sectors, a fundamental question is if the VC opportunity set excluding these sectors is compelling enough relative to opportunities outside of China to justify continued investment, especially if China’s domestic technology development is slowed by US restrictions. While themes such as advanced manufacturing, robotics, clean-energy, and electric vehicle production are current strengths of China, they could also be constrained by lack of access to cutting edge semiconductors and computing power. Further, exit pathways for initial public offerings (IPOs) have become more constrained in recent years. IPOs on US exchanges now require time-consuming approvals, while exiting via the onshore markets or Hong Kong still have tighter listing requirements relative to the United States. Further reforms may occur, but the longer journey to IPO will pressure portfolio internal rate of returns and add a layer of increased currency risk for foreign investors relative to the past.

At the same time, domestic renminbi (RMB) VC funds are seeing an increase in fundraising and activity. There are signs that Chinese entrepreneurs in sensitive sectors are shunning USD-capital and preferring domestic RMB capital and seeking out non-US investors, particularly from the Middle East where there is growing political support to invest in China. Large state-backed pools of capital in China are also stepping in to fill the void left by the pullback in foreign capital. RMB funds have historically had less favorable terms and face similar IPO challenges as USD funds. While there are ways for foreign investors to access these funds, they come with distribution regulations for foreign investors that slow both exits and currency repatriation.

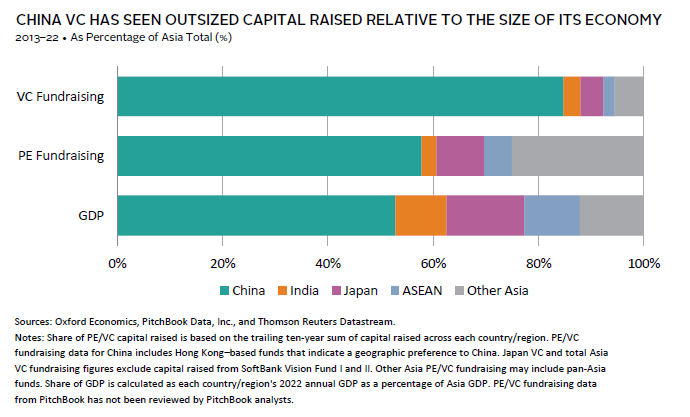

As a result, China is unlikely to continue to receive a disproportionate amount of capital flows relative to the rest of Asia. For instance, over the past decade China has received 85% of Asia VC fundraising, despite accounting for only half of Asia GDP. Reduced capital flow may result in better entry valuations, and therefore help compensate for some of the uncertainty arising from a reduced opportunity set and exit channels, for investors willing to bear the political headline risk surrounding China tech investments. Chinese PE growth equity funds, which focus more on consumer and healthcare investments, may be more insulated from the technology tensions and benefit from multinationals seeking to offload their China operations due to geopolitical pressure/de-risking.

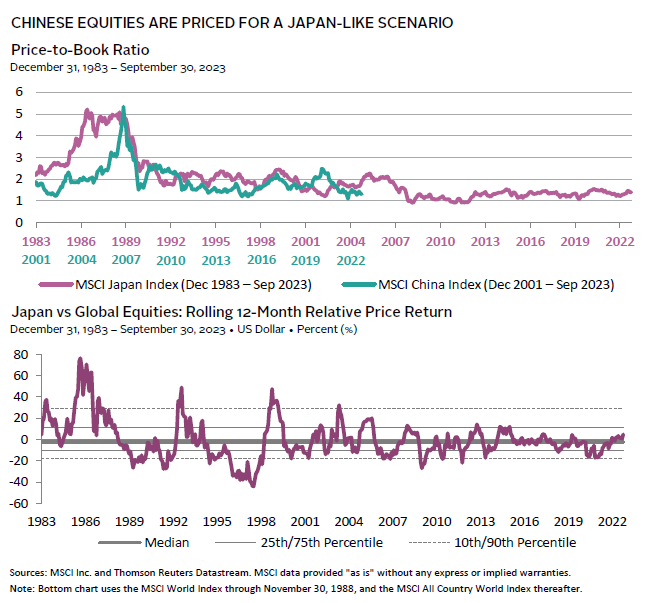

At the same time, Chinese public equity markets have languished amid the stalling Chinese economic recovery and negative sentiment. Chinese economic data have shown signs of stabilization because of recent policy support measures. However, investors remain concerned the modest actions taken thus far will not prevent China from falling into a property bust/deflation/demographic funk like what has occurred in Japan over the past few decades. Whether China decides to act aggressively to support the property sector remains to be seen and is partly a function of whether the government has a higher tolerance for economic pain than in the past. Given the structure of the Chinese banking system, the odds of a financial crisis in China are still low since state-owned banks can restructure debt and the closed capital account keeps domestic savings trapped at home. At the same time, Chinese equities are already priced for a Japan-like scenario, and during Japan’s lost decades there were periodic bursts of outperformance versus global equities driven by cyclical upturns in the economy (partly driven by increased stimulus), a situation China may be on the cusp of today. Thus, we think public equities present a near-term opportunity, despite the slower growth outlook for China.

Amid the shifting landscape, the bottom line is that global investors need to follow the Chinese idiom of “crossing the river by touching the stones.” In other words, move slowly and take a more selective approach toward deciding which opportunities to pursue, particularly on the private investment side, as GPs and LPs adjust to the new environment and as some Western investors may choose to shun China investments for political reasons. To the degree Western investment flows subside, it will create opportunities for those investors willing to step into a less crowded space.

Conclusion: Changes Are Already Afoot

The trade and financial decoupling between the United States and China is occurring faster than anticipated. The United States is unlikely to change its strategic policies toward China anytime soon (regardless of who wins the upcoming 2024 elections). China’s shifting ideological focus from economic development to national security and self-sufficiency is also unlikely to change, although China is capable of abrupt shifts in policy when needed.

These geopolitical realities create additional investment opportunities in Asia, as China is unlikely to continue to receive the lion’s share of global investment flows into the region, despite the large size of its economy. Investors should expand the aperture of their investment lens to include Asian equity opportunities beyond China, which we discuss in more detail in Part II of this series.

The wider focus on Asia does not imply there are no attractive investment opportunities in China. Indeed, we think investors willing to overweight Chinese public equities relative to global equities will benefit, as relative valuations are depressed enough to offer potential outperformance should short-term sentiment toward China shift amid signs of more aggressive policy actions to support the economy.

Regarding China PE/VC, we think investors need to be very selective given the shifting dynamics and opportunity set and we do not see a near-term thaw in the frozen fundraising cycle for China PE/VC until there is clarity on how the US executive order will be implemented and managers and investors have time to digest and adapt to the new rules. Hard-tech deals in sensitive sectors may simply shift toward domestic investors and non-US investors willing to invest in RMB fund vehicles. Meanwhile USD capital will be focused on VC investments in other sectors and strategies such as buyouts and growth equity that face fewer geopolitical hurdles. Less capital chasing deals may result in better entry valuations and opportunities for investors (both US and non-US) willing to tolerate the uncertainty and headline risk in China. At the same time, the shifting geopolitical landscape creates other investment opportunities in Asia that deserve a closer look.

Celia Dallas, Chief Investment Strategist

Aaron Costello, Regional Head for Asia

Vivian Gan, Associate Investment Director, Capital Markets Research

David Kautter also contributed to this publication.

About Cambridge Associates

Cambridge Associates is a global investment firm with 50 years of institutional investing experience. The firm aims to help pension plans, endowments & foundations, healthcare systems, and private clients implement and manage custom investment portfolios that generate outperformance and maximize their impact on the world. Cambridge Associates delivers a range of services, including outsourced CIO, non-discretionary portfolio management, staff extension and alternative asset class mandates. Contact us today.

Index Disclosures

MSCI All Country World Index (ACWI)

The MSCI ACWI captures large- and mid-cap representation across 23 developed markets (DM) and 24 emerging markets (EM) countries. With 2,947 constituents, the index covers approximately 85% of the global investable equity opportunity set. DM countries include: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. EM countries include: Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Czech Republic, Egypt, Greece, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Korea, Kuwait, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, the Philippines, Poland, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates.

MSCI China Index

The MSCI China Index contains 717 constituents and captures large- and mid-cap representation across China A-shares, H-shares, B-shares, red chips, P chips, and foreign listings. Currently, the index also includes large- and mid-cap A-shares represented at 20% of their free float–adjusted market capitalization.

MSCI Japan Index

The MSCI Japan Index is designed to measure the performance of the large- and mid-cap segments of the Japanese market. With 235 constituents, the index covers approximately 85% of the free float–adjusted market capitalization in Japan.

MSCI World Index

The MSCI World Index represents a free float–adjusted, market capitalization–weighted index that is designed to measure the equity market performance of developed markets. It includes 23 developed markets country indexes: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Footnotes

- ASEAN includes Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

- China’s Belt and Road Initiative is a vast infrastructure and development plan launched in 2013. The original initiative was to link East Asia and Europe. Since then, the project has expanded to more than 150 countries, including in Africa, Latin America, and Oceania.

- The US executive order does not explicitly prohibit investment by US LPs, but the US Treasury will provide final clarification in the coming months.