Policymakers are in a tough spot. One doesn’t need to look further than the United Kingdom to see their challenges. High inflation and slowing growth have pitted central banks against politicians seeking to stimulate. As a result, capital markets of all sorts—risky and defensive—have corrected sharply. Much bad news has been discounted, but is it enough? In this edition of VantagePoint, we review three big questions that are central to the path of the markets:

- Will the US Fed pivot away from aggressive tightening?

- Will China move away from its zero-COVID policy?

- Will Europe successfully manage its transition away from Russian energy imports?

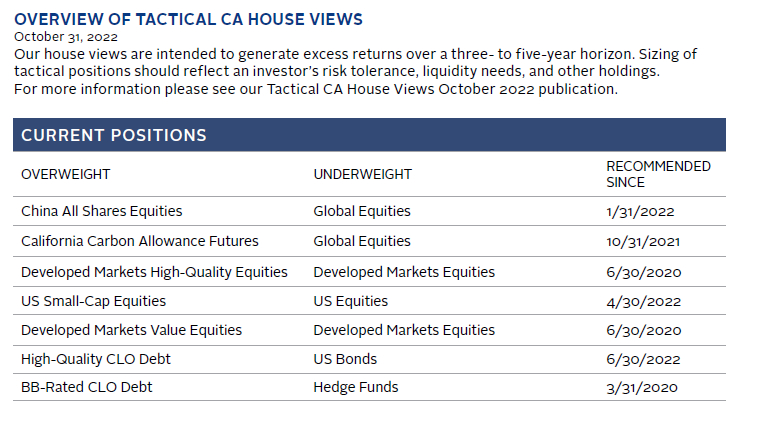

We conclude that the Fed is more likely to pause than pivot, but significant tightening is priced in to justify neutral bond duration relative to policy. Beijing may take some time before it is willing to significantly relax zero-COVID policy, but once they do, Chinese equities are poised for a meaningful rebound. Finally, Europe’s transition away from Russian energy will be both challenging and costly, yet markets are discounting enough pessimism for us to be neutral on European equities.

1. Will the US Fed Pivot Away From Aggressive Tightening?

We see a pause as more likely than a pivot. The Fed has indicated they will “keep at it” until the policy rate is restrictive and they feel confident that inflation is on a path back to their 2% target, even if this results in recession. Indeed, the Fed projects that unemployment will increase to 4.4% next year as they tighten. Such an increase in unemployment has never transpired without a recession. Historically, the Fed typically would then ease, but we see this as unlikely without a concurrent sharp decline in inflation. We suspect inflation will be slow to decline, causing a prolonged pause before a pivot.

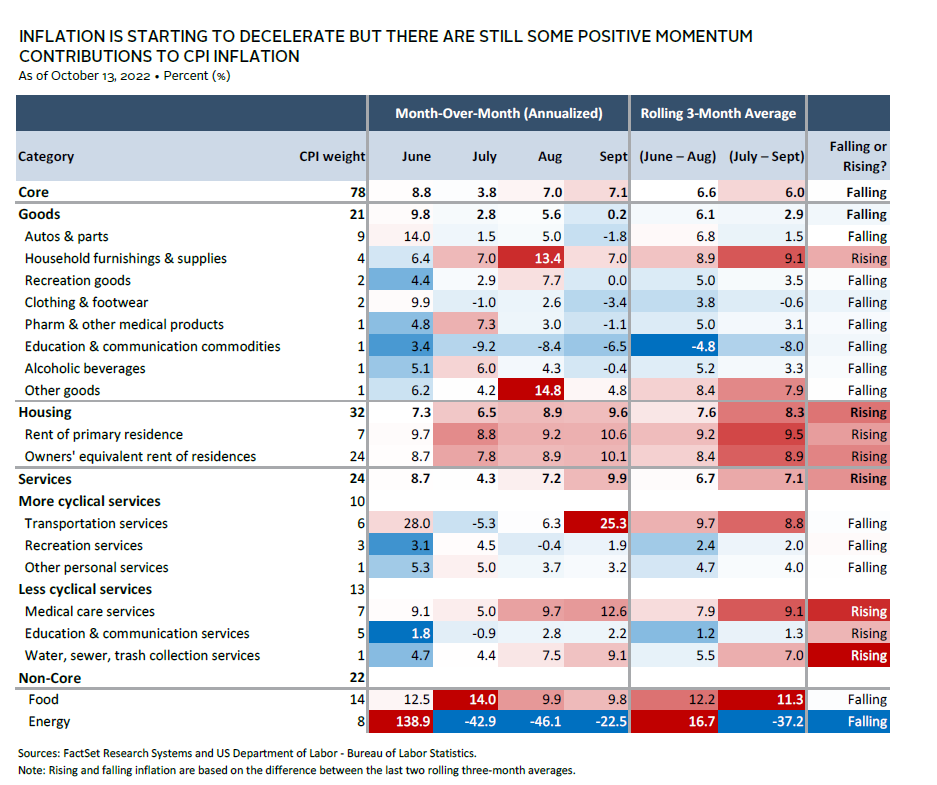

Inflation is starting to decelerate in some segments of the economy as shown in the table below. However, less-cyclical services, housing, and household-related goods continue to accelerate. The key factors for inflation are wages—the main driver of inflation for much of the service sector—and the health of the housing market, as housing makes up nearly a third of the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Wages are supported by persistent labor market strength and will only ease as the economy softens, a change that the Fed is trying to orchestrate. The latest labor report showed unemployment fell back to recent lows of 3.5% amid lower, but still robust, job growth and elevated quit rates. Wages continue to increase, even as the pace over the last two months has slowed to an annual rate of 3.6%—a level consistent with a 2% inflation target. Real wages are obviously in decline with headline inflation clocking in at 8.2% in September. Encouragingly, the number of job openings fell by 10% in August, so the labor market has softened some, but it remains unmistakably tight.

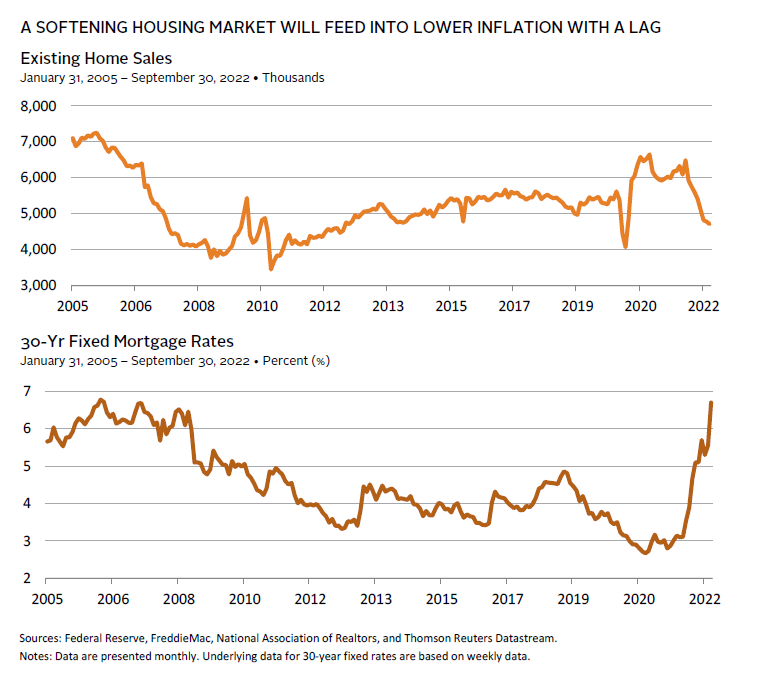

As for the housing market, the sharp increase in rates this year has seen 30-year mortgage rates more than double, and home sales have plunged. Inventories are elevated and home prices are starting to fall. In July, the S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller National Home Price Index fell for the first time since January 2019, declining 0.5% and then again in August by 1.1%. The CPI measure of inflation will likely continue to rise before it starts to fall, as it tends to lag home prices, but this sizeable segment of inflation will probably start declining next year.

As of late-October, the market is pricing in that the Fed will stop tightening in May 2023 with a terminal rate of 4.9%, at which point it will begin easing. This would imply a relatively typical tightening cycle based on the average tightening since 1965 and may understate necessary tightening, given inflation is well above what is typical for most of this period. Should the Fed keep conditions tighter than priced in for longer, equity and fixed income markets will experience more losses before eventually recovering as the Fed ultimately pivots. However, a significant degree of tightening is priced in and ten-year Treasury yields at roughly 4% offer reasonable value. Further, markets are pricing in a long pause, with the Fed funds rate remaining above 4.5% until January 2024. For investors that have been underweight duration, we would seek to move to more neutral positioning relative to investment policy.

While not our base case, a faster Fed pivot would require extreme circumstances—either economic growth slows more sharply than anticipated or “something breaks.” An extreme circumstance could arise due to the rapid pace of conventional tightening along with quantitative tightening. On average, tightening cycles have lasted 22 months. Thus far, the Fed has tightened by 300 basis points (bps) over just six months. Add in the 190 bps of additional tightening priced into the market, and that would mean 490 bps over 14 months. Another possibility is that an extreme circumstance develops in connection to the lengthy period of exceptionally low rates. This likely supported excessive speculation and proliferation of risk-management systems that fail to adequately account for the risk of rising interest rates. While it is unknown how sharp a rate increase is required to ignite these risks in the United States, we do know most investors will not be able to time the bottom, and those who do might just be lucky.

2. Will China Move Away From Its Zero-COVID Policy?

The Chinese government has already pivoted on two aggressive regulatory initiatives, and we believe an easing of China’s zero-COVID policy is next. However, the timing is not likely until after first quarter 2023. The Chinese economy and equity markets have been pummeled over the past two years largely due to self-inflicted policy actions, starting with the regulatory crackdown on the technology sector, a deliberate tightening of credit to the real estate sector, and the ongoing zero-COVID policy and related frequent lockdowns. Since its peak in February 2021, the MSCI China All Shares Index is down more than 50%, underperforming global equities by a wide margin. At the same time, Chinese real GDP grew only 0.4% year-over-year in second quarter 2022 and rebounded to only 3.9% in third quarter 2022, still far below the 5.5% government growth target for the year.

Given the challenging economic backdrop, the recently concluded Party Congress in October has disappointed markets by failing to signal any meaningful change in government policies or priorities. As expected, the Party Congress has confirmed Xi Jinping’s third term as the leader of the Party (and thereby China) and has unveiled the other members of the Politburo, which is now composed almost entirely of Xi loyalists and further cements his political power.

Xi Jinping’s opening speech of the Party Congress focused on the themes of strengthening national security, technology self-sufficiency, and economic development amid a challenging geopolitical backdrop. While Xi’s speech did not deliver any surprises or fundamental changes in existing policies, the conclusion of the Party Congress should help alleviate the current political and policy inertia in China, given lower-level officials (and business leaders) now have more clarity on power dynamics and priorities.

Indeed, we think that some changes are already afoot. First, the regulatory crackdown has effectively ended as China, over the past year, has provided clarity on a slew of regulations facing the technology sector, including overseas IPOs, VIE structures, and foreign audits. Although China has not rolled back the anti-monopoly regulations put in place in 2021, Chinese tech companies have acknowledged the new regulations and changed previous practices to better align with the government’s “Common Prosperity” theme. While investor skepticism remains, for now the regulatory crackdown is over. Indeed, the Common Prosperity theme was somewhat downplayed during Xi Jinping’s speech.

China has also eased monetary policy and lifted restrictions to help support the real estate sector. China has been trying to reduce leverage in the real estate sector for some time, and, by late 2021, the policy and general monetary tightening caused a larger-than-anticipated slowdown in real estate activity. The government has since clearly pivoted to a stance of general monetary easing and lifting of restrictions on the property sector, including the establishment a $150 billion funding plan to help healthy developers take over uncompleted projects of stressed developers. While analysts argue that more support is needed to deal with the issues, government policy is now focused on containing any systemic fallout from the property developer crisis. However, it is also clear that the government does not want to trigger a debt-driven rise in construction activity and property prices. Thus, any rebound in the real estate sector will be modest and alone will not revive China’s economy.

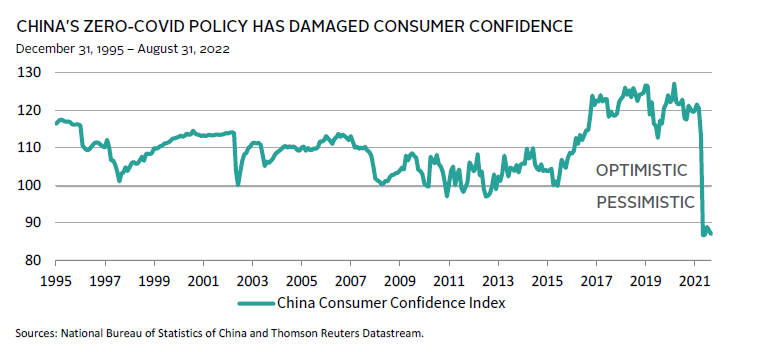

This leaves zero-COVID as the last major policy pivot for China. China has been effective at containing the spread of the virus and limiting COVID-related deaths, but the economic costs are mounting. Consumer confidence has collapsed to record lows, and urban youth unemployment is at a record high of 20%. Frequent lockdowns, even if short in duration, create a sense of uncertainty for households and businesses that hold back spending and investment, including property investment. Thus, it is hard to see a meaningful economic recovery without some form of policy shift on COVID-19.

It remains to be seen when this shift will occur. Xi Jinping’s opening speech of the Party Congress defended China’s zero-COVID policy and did not signal any immediate change in policies. However, behind the scenes small policy changes continue to occur, including the resumption of issuing business and tourist visas to China, increased flight routes, the removal of quarantine for arrivals in Hong Kong, and the potential reduction in quarantine time for Hong Kong–China cross-border travel. Our sense is that continued small policy tweaks following the Party Congress will set the stage for an eventual shift, considering the dire state of the economy. However, meaningful change in policy may not occur until after first quarter 2023, given the required tilt in government rhetoric and because major policies are formally approved and adopted at the National People’s Congress in March. There is also the desire to wait until any winter surge in global COVID-19 cases passes. Other analysts warn that a shift may not take place until China has developed its own mRNA vaccines or other treatment breakthroughs that make the leadership more confident that China’s healthcare system can handle any surge in COVID-related hospitalizations, suggesting a policy shift won’t occur until much later in 2023.

Waiting is the Hardest Part

Due to the current uncertainty, the Chinese economy and equities are like a coiled spring, waiting for the downward pressure to be lifted. The market sell-off following the Party Congress shows that investors have now capitulated on any near-term recovery. Because valuations for Chinese equities are currently depressed, we think investors are compensated for the heightened uncertainty, especially since markets could react quickly and powerfully to any change in zero-COVID policy, making it very difficult for investors to time this pivot.

Furthermore, a 2023 Chinese economy recovery could see Chinese equities outperform global markets amid a monetary policy–induced slowdown in the United States and Europe. China is not facing the same inflation pressures seen globally (headline inflation is running at 2.8%), given the depressed state of the economy. This gives China scope to further increase fiscal and monetary stimulus while the rest of the world grapples with rising interest rates. This divergence in economic cycles adds another layer of optionality and diversification that Chinese equities bring to global portfolios. Yet it is hard to see any sustained market recovery in China without a meaningful easing of COVID-19 policies, which still seems several months away.

3. Will Europe Successfully Manage Its Transition Away From Russian Energy Imports?

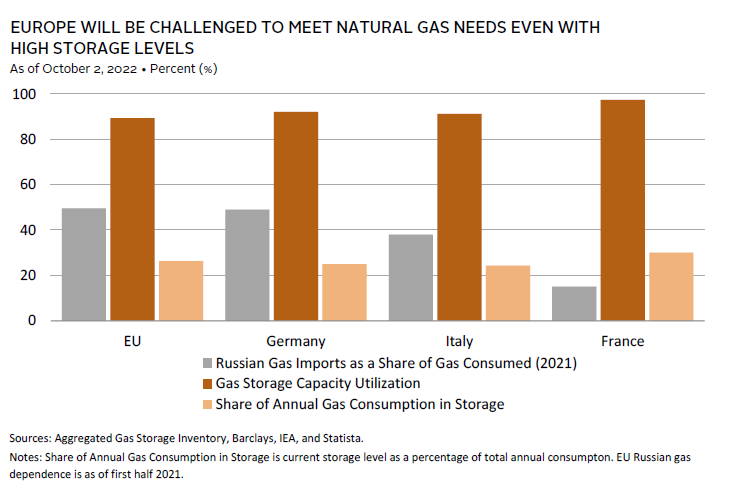

Nearly half of the EU’s gas and a quarter of its oil was sourced from Russia in 2021. We expect Europe to ultimately be successful in its move away from Russian energy, but this move will take years and comes with a high price tag that will weigh on economic growth and pressure inflation. Wholesale prices for electricity have risen five to 15 times since the first half of 2021 and gas prices peaked at roughly 20 times their early-2021 lows. European governments are providing relief to shield consumers and corporations from the price shock to varying degrees. However, central banks are seeking to address high inflation by raising interest rates to rein in demand. What is certain is that a meaningful amount of pessimism about economic growth is priced into capital markets, keeping us neutral on European equities.

A Good Start, Especially With a Warm Winter

To offset the elimination of Russian gas, Europe is importing gas from other sources to the degree that its infrastructure allows, building more liquefied natural gas terminals to increase import capacity, accelerating renewables investments, and seeking to reduce consumption to maximize natural gas storage ahead of the high-demand winter season. To complicate matters, the region is suffering a loss of hydro power and nuclear production. In July, the International Monetary Fund reckoned that alternative sources could replace two-thirds of Russian gas over the next year. The EU overall may well squeak by this winter. However, if the winter is unusually cold, resulting in above-average demand, alternative energy supplies and storage may not be enough to meet demand without forced rationing. The situation is more challenging in Germany and Italy, even as both countries appear set to meet their gas storage objectives. Natural gas accounted for about 24% of the EU’s energy mix in 2020, with Germany at 26% and Italy at 41%, nearly all of which was imported.

Most analysts expect that it will take at least two to three years before Europe can adjust to the elimination of Russian energy imports. Looking beyond this winter, Europe will need to source gas and refill storage, likely without any Russian gas, putting continued pressure on gas prices and economic growth.

Economic Growth Will Take a Hit

Corporations have found it challenging to fully pass cost increases on to end customers who are seeing real disposable incomes eroded by high inflation, especially food and energy costs. As a result, the industrial sector has cut production, with the euro area manufacturing output falling nearly 2% since January. A weaker euro could potentially advantage exports; however, its fall has been primarily against the US dollar and currencies of commodity exporters rather than major export markets or export competitors. 1

Consensus estimates for GDP growth seem to be accounting for much of this stress. Since March, the consensus 2023 GDP growth forecast for the Eurozone has fallen 250 bps to 0.0%. At the same time, Europe is struggling with higher inflation that has broadened beyond energy in recent months. Central banks are likely to maintain a tightening bias. Meanwhile, governments are engaged in large-scale fiscal interventions aimed at easing the pain of rising energy prices. As we saw in the United Kingdom, such fiscal measures may cause indigestion if they result in concerns over long-term financial stability, although the subsequent announcement by Germany that it will spend €200 billion, or 5.6% of 2021 GDP, to provide aid to businesses and consumers struggling under high energy costs has not met with the same punishment from investors.

Are Equity Markets Pricing in the Stress?

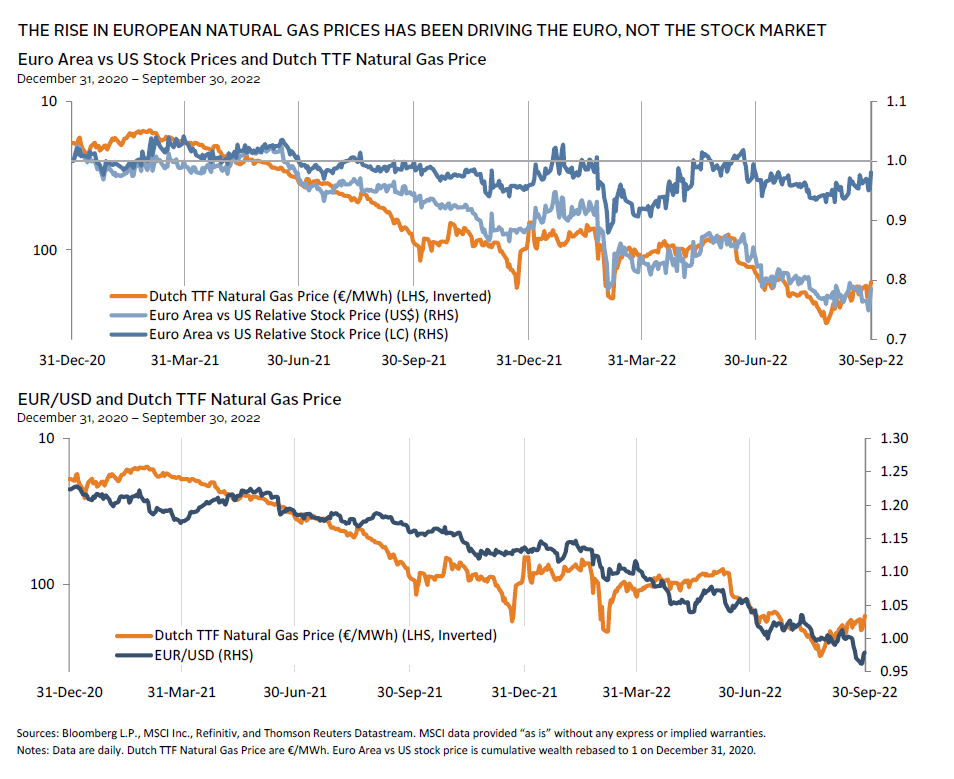

Euro area equities have fallen substantially this year, bringing valuations in line with their historical averages. Relative to US equities, euro area stocks have held up better in local currency terms but have underperformed sharply in US dollar terms. The euro has lost ground to the dollar this year even as interest rates have started to converge. Markets have adjusted to Europe’s narrowing current account surpluses, dragged down by expensive energy imports and relatively low growth expectations, while the US dollar continues to benefit from safe-haven inflows. Indeed, as shown in the chart below, the underperformance of euro area equities relative to the United States has moved in lock step with the increase in European natural gas prices, largely driven by the weakening euro. In other words, the euro has served as a relief valve while valuations have remained flat, although somewhat cheap, compared to global developed markets at about the 25th percentile of the historical distribution.

Consensus earnings expectations for the region have also been downgraded, with euro area earnings expected to grow just 2.8% in 2023. Such estimates are not pricing in steep earnings declines (25%–50%) associated with recessions but are the lowest consensus growth estimates since our data began in December 1987 and are well below the rate of inflation. 2

These data suggest that most of the energy distress for the euro area has been priced in, although this is largely reflected in the euro rather than equities. As such, the euro would be the main beneficiary of any positive surprise should Europe manage the energy crisis better than currently anticipated. European equities would also benefit under such circumstances, but perhaps not by more than equities globally as a whole. We would expect a rotation within the equity market away from energy stocks and toward more cyclical sectors and more energy-intensive sectors, like chemicals. Market pricing reflects the outsized risk European equities are facing and we remain neutral on the equity market.

Conclusion

We are certainly living in unprecedented times with high inflation, disrupted supply chains, a war in Ukraine, and an unusual mix of tight monetary and, in some cases, easing fiscal policy. While the range of possibilities for risk assets are wide, we expect more downside and volatility near term as policymakers work through these challenges. Still, valuations have improved, reducing risk and creating opportunities in some market segments. Rather than try to perfectly time the bottom, investors should focus on maintaining adequate diversification, disciplined rebalancing, and taking advantage of attractive opportunities as they develop, recognizing that timing is not going to be perfect and doesn’t need to be if you have an appropriately long time horizon and the fortitude to withstand volatility.

Vivian Gan and Kristin Roesch also contributed to this publication.

Index Disclosures

China Consumer Confidence Index

In China, the Consumer Confidence Index is based on a survey of 700 individuals over 15 years old from 20 cities all over the country. This composite index covers the consumer expectation and consumer satisfaction index, measuring the consumers’ degree of satisfaction about the current economic situation and expectation on the future economic trend.

MSCI China Index

The MSCI China Index contains 717 constituents and captures large- and mid-cap representation across China A-shares, H-shares, B-shares, red chips, P chips, and foreign listings. Currently, the index also includes large- and mid-cap A-shares represented at 20% of their free float–adjusted market capitalization.

MSCI World Index

The MSCI World Index represents a free float–adjusted, market capitalization–weighted index that is designed to measure the equity market performance of developed markets. As of December 2017, it includes 23 developed markets country indexes: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Footnotes

- On a real effective trade-weighted basis against major currencies, the euro has fallen just 4% year-to-date through August 30.

- Based on October estimates of the subsequent calendar year earnings growth. The MSCI EMU earnings growth estimate of 2.8% is also the lowest on record based on this methodology.